By Daniel Smith

The history of Colorado is colorfully imbued with the historical characters who shaped and created it as the westward expansion of America grew.

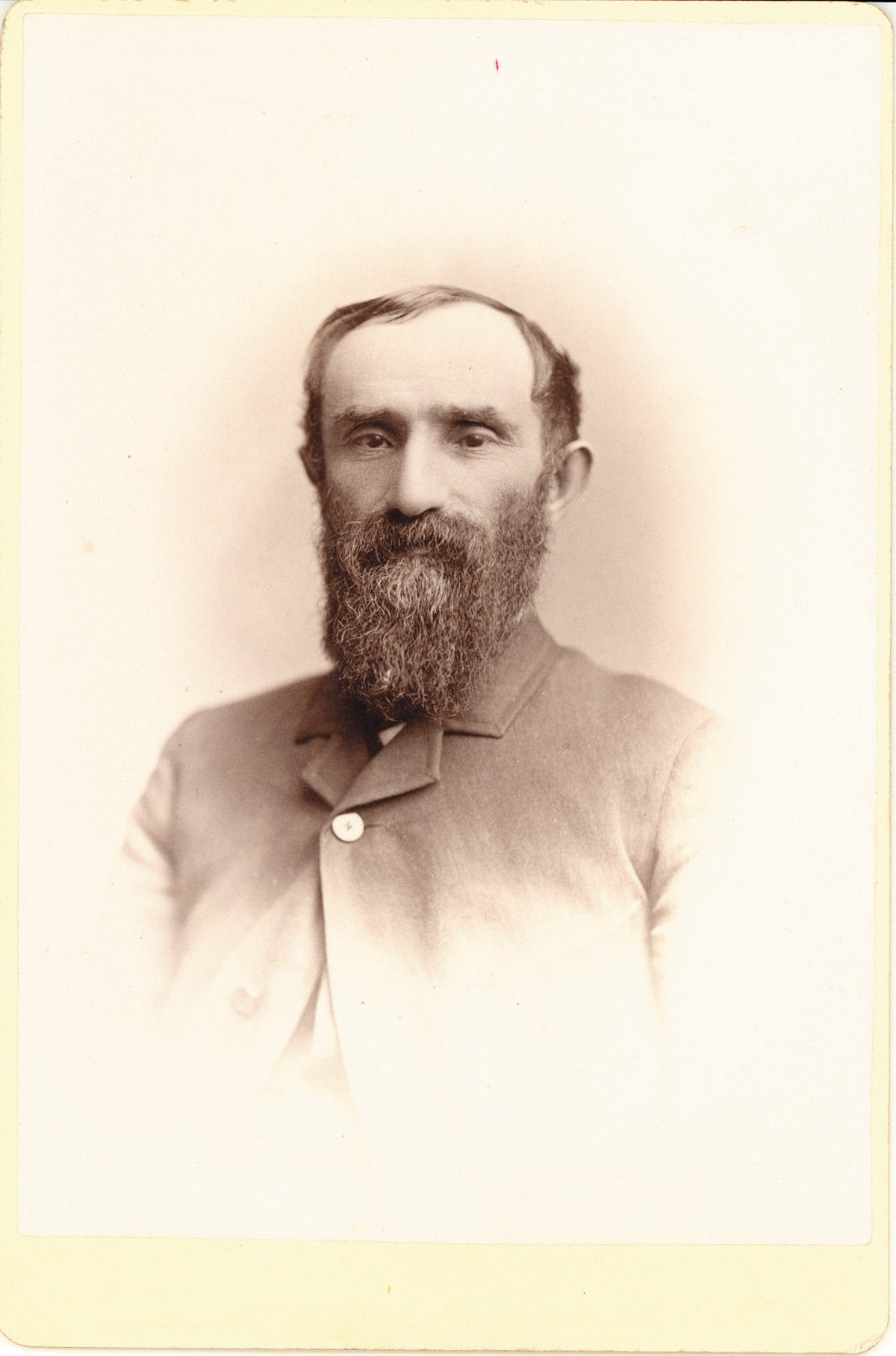

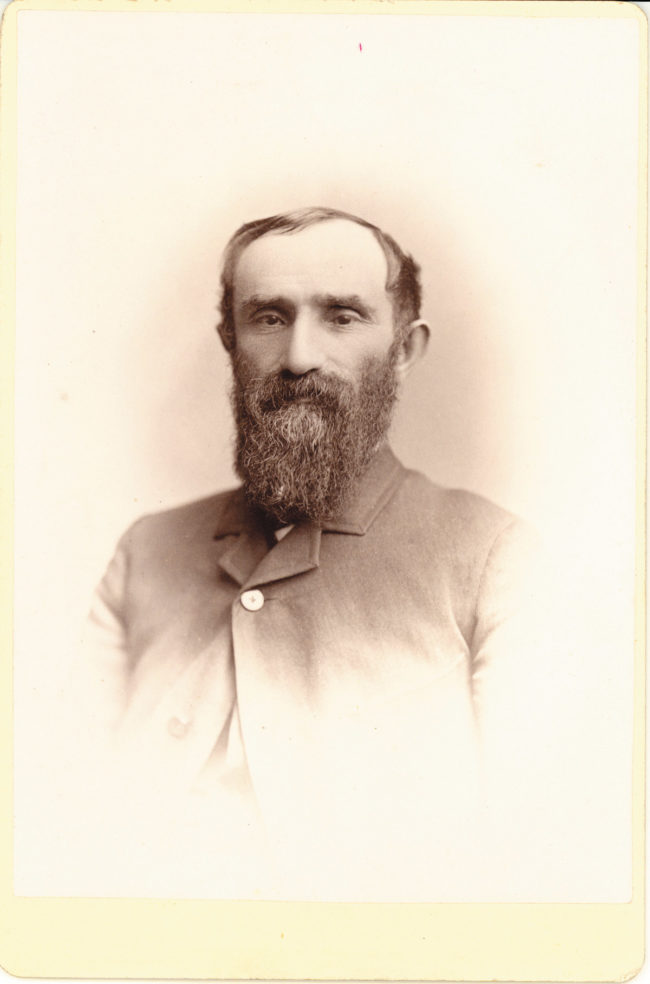

Otto Mears stands as a giant in that history, not only for his numerous enterprises creating infrastructure and economic development, but his political impact and ability to be involved in many aspects of pioneer life of the region simultaneously.

His legend is spelled out in books, including Otto Mears and the San Juans by E.F. Tucker and Otto Mears, Pathfinder of the San Juans by Ruby G. Williamson among others and numerous articles written about his accomplishments. We can only briefly detail much of that life here.

He licked heavy odds from his orphan childhood onward to become a figure of enormous importance in the region and state. In short, Mears scope of operations included building pioneering trade businesses, building many vital roads, operating newspapers, running mines, building a first sawmill and grist mill, becoming a local and Colorado political force. He was a friend and benefactor to the Ute Indian Tribe and worked as part of a team that got the state capitol built.

In 1927, his friend Charles Tarvell of Saguache described this proactive, energetic man this way:

“Mr. Mears is a man who always said, ‘I can,’ – and he did.”

Mears personal history in his own autobiography is testament to an indomitable spirit shown at a young age.

Born May 3, 1840 in Kurland, Russia, (now Lativia) near the Baltic Sea. His mother, and perhaps his father, were Jewish. His father died when he was but one year old, and his mother died before he turned three.

He apparently was taken in by her brother, but Mears later wrote his relatives didn’t like him – details are sketchy – but it seems he was sent to an uncle on his father’s side and sailed to England on a lumber merchant ship when he was but nine years old.

In her book, Tucker writes he took a first train ride there in searching for other relatives, and was then sent by an uncle to New York City by boat, where he was kept for a year by another relative before being shipped out again, this time to San Francisco to another uncle.

[InContentAdTwo] It was 1851, a couple of years into the California Gold Rush and Mears was but 11 years old when he learned the uncle he was to stay with had apparently just left for Australia. Befriended by an unidentified older women, he stayed at a rooming house with her and began working day and night, selling newspapers, learning the tinsmith trade, working for merchants, working mines there and in Nevada before going back to San Francisco, voting for Abe Lincoln as president and joining the California Volunteers when the Civil War broke out.

The resourceful young man learned to bake bread for the Army and was able to sell the extra flour he didn’t use and save about $1,500.

Mears fought against Texans in New Mexico and fought the Navajos under Kit Carson until he was discharged in a small town in New Mexico. With another $200 in gold from the Army, he and other soldiers ventured to Santa Fe to seek their future.

The ambitious Mears took a job at a clothing store there and learned the ropes well before moving to Conejos in the San Luis Valley and opening his own store.

He and Major Lafayette Head, then in charge of the Indian Commission (and later to be Lieutenant Governor) partnered to build the first sawmill and gristmill for grain in the area – no small accomplishment.

Enthusiastic community activists, including Steve Stewart, who is restoring the historic hotel on Fourth Street, next to where Mears’ hotel in Saguache once stood, would like to see his legacy get more focus, and Saguache and attractions and nearby communities become more of a destination for Colorado travelers.

Means’ business savvy becomes readily apparent since the government then was paying $20 for a hundred pounds of flour for troops at Fort Garland and $80 per thousand feet of lumber.

Mexican-raised wheat at the time wasn’t sufficient, so Mears established 200 acres of his own to farm and raise wheat for the mill and ended cutting grain by hand and threshing by sheep when he brought the first mower, reaper and threshing machine to the San Luis Valley.

When the price of flour fell to five dollars a hundredweight, Mears decided against hauling to Fort Garland in favor of Poncha Pass down to Charles Nachtrieb’s mill in the Nathrop area to sell to mines in Granite and California Gulch (now Leadville). The 9,000-foot pass was only a rough path, and a mishap hauling grain in his open wagon led to another chapter in his unique story.

His wagon was upset, the grain spilled, and as he shoveled it back into the wagon, Territorial Governor William Gilpin happened upon him on horseback. Mears describes him as “a very able man, but rather crazy.”

Gilpin asked Mears why he didn’t take out a state charter for a toll road through the area and just build it. The charter would cost five dollars.

After delivering his grain, that’s just what Mears did – got the charter in Denver (no maps or engineering plans required) and started building his first toll road. It ran from Poncha Pass, north along Poncha Creek to where it joined the Arkansas River. He and the mill owner were sole investors in the Poncha Pass Wagon Road Company – about a $2,000 outlay. Later, it was extended to Nathrop where it intersected the stage road between Leadville and Denver. Before passable roads, hauling any freight or passengers often required burros and other pack animals over treacherous terrain in all kinds of weather.

From that start, Mears built many more roads in Southwest Colorado – even later in other parts of the country – and had more enterprises in freighting goods for customers over those roads. His highest road went from Ouray to Silverton and on to north of present Ridgway.

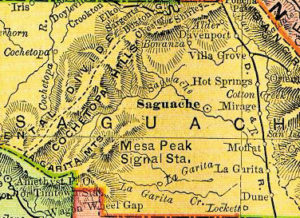

His second road was from Saguache to Lake City over Cochetopa Pass and Los Piños Creek. His road network unpinning the region’s development and gold and silver mining would eventually stretch for 450 miles. The Pathfinder of the San Juans was prospering from his hard work and vision.

[InContentAdTwo] He opened a new mercantile in Ouray in 1877 and was also now active politically, helping business associate Frederick Pitkin get elected Colorado governor, then started his most ambitious road project, from the terminus of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad at the South Arkansas River across Marshall Pass to Gunnison with a couple of partners. He sold the road to the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad in 1881.

Also during this time, the multi-tasking Mears had befriended some of the Utes, including Chief Ouray, learned their language, and became a moderator and interpreter between the Utes and the government from the mid-1860s until he resigned his commission after most of the Utes had been driven out by the growing European expansion of Manifest Destiny – in the pioneer West.

The Utes were going to be moved to reservations in this shameful period of our history. Mears was contracted to aid the effort providing government-promised goods and animals to the Los Piños Indian Agency as well as building a road from Saguache to Los Piños.

Researching Mears’ history shows a multi-faceted man who, (as with many “movers and shakers,”) displays both business cunning and compassion, a generous nature and a hard-edged business philosophy. He fought against unionization of railroads and mines for instance, but was progressive in his approach to treatment of workers. His political accomplishments were many, but he was known to embrace underhanded political dealing and bribery as a means to an end. He befriended the Utes, but was also instrumental in their removal from Colorado.

As this expansion was coming to fruition, true to his nature, Mears also got involved in building three narrow-gauge railroads in the high alpine country. We learn from The Rainbow Route by Robert Sloane and Carl Skowronski, the routes were the largest factor in the success of no less that 20 mines in the area and the livelihoods about 200,000 people over a half-century.

He created and financed the Rainbow Route, starting with the Silverton Railroad, running from that town to Red Mountain. He obviously recognized the need for cheaper means of hauling countless tons of ore that only a railroad could provide. After the Silverton, he built the Rio Grande Southern from Ridgway through Telluride and the Silverton Northern north and east to Animus Forks. Among his innovations was having an engineer design a unique turntable on the narrow mountain switchback route for the number 100 engine Mears liked, which he called Ouray.

His technical innovations also included a unique “railroad bicycle” built with a platform with rubber tires to roll on the narrow-gauge tracks, powered by two stationary bikes side by side, pedaled with the chains driving the rear wheels.

The visionary had plans for an electric railroad in the future, and even extended his railroad dreams to Phoenix and San Diego, but the silver crash of 1893 caused the closing of many mines and made the projects unfeasible. About half the working mines failed, hundreds of businesses closed.

This situation caused a considerable financial setback for Mears, but as with the whole scope of his life, his tenacity and ingenuity saw him through.

His Rio Grande Southern Railroad went into receivership and was sold to the Denver and Rio Grande in 1895.

In 1897, he accepted an offer from the head of the Denver and Rio Grande to move back east to help complete the Chesapeake Beach Railway between Washington D.C. and Chesapeake Beach, Maryland. He also was involved in planning to build a railway between Monroe and New Iberia, Louisiana, and on to New Orleans. The project never reached full fruition, eventually operating on a short 33 miles of track.

Returning to Colorado, Mears focused on new mining operations when he could not expand his railroads.

He leased what was called the Iowa-Tiger mine in 1908 despite a poor financial history and returned it to profitability by hiring the best miners and giving them a share of the mine profits.

After that mine boom in 1911, Mears leased the Gold King at Gladstone, hoping to revitalize it enough to produce ore-hauling profit for the Silverton, Gladstone and Northerly Railroad he had lease three years earlier. Eventually, gold was discovered and the mine was producing six to eight carloads of ore daily. The Gold King Mine presumably is the same one that made headlines when backed-up water was accidentally released a few years ago, fouling the Animas River.

Other mining operations, aided by new innovations processing more precious ore from tailings helped him recoup some of his lost wealth, a boom-bust-boom financial recovery process he had repeated often before.

In 1920, he terminated his last mining leases in Silverton, left politics and retired with his wife, Mary, in California, his remarkable working life concluded.

The remarkable life of Otto Mears came to an end in a California nursing home, June 24, 1931. He made a last trip to Colorado in 1929 before his health began to fail.

His far-reaching impact as the builder of much of the early Colorado transportation systems is too often overlooked, even in areas where his impact was greatest. His legacy needs to be preserved.

There is at least one stone monument, in the mountains, to his route-building, a Liberty ship built in 1943 in California was named for him and Mears Peak stands at nearly 13,500 feet on the Ouray-San Miguel County line.

Daniel Smith is a former Denver newspaper and broadcast journalist who retired to Salida for freelance writing, photography, relaxation and finding time to lie about fly fishing.