By Wayne Iverson

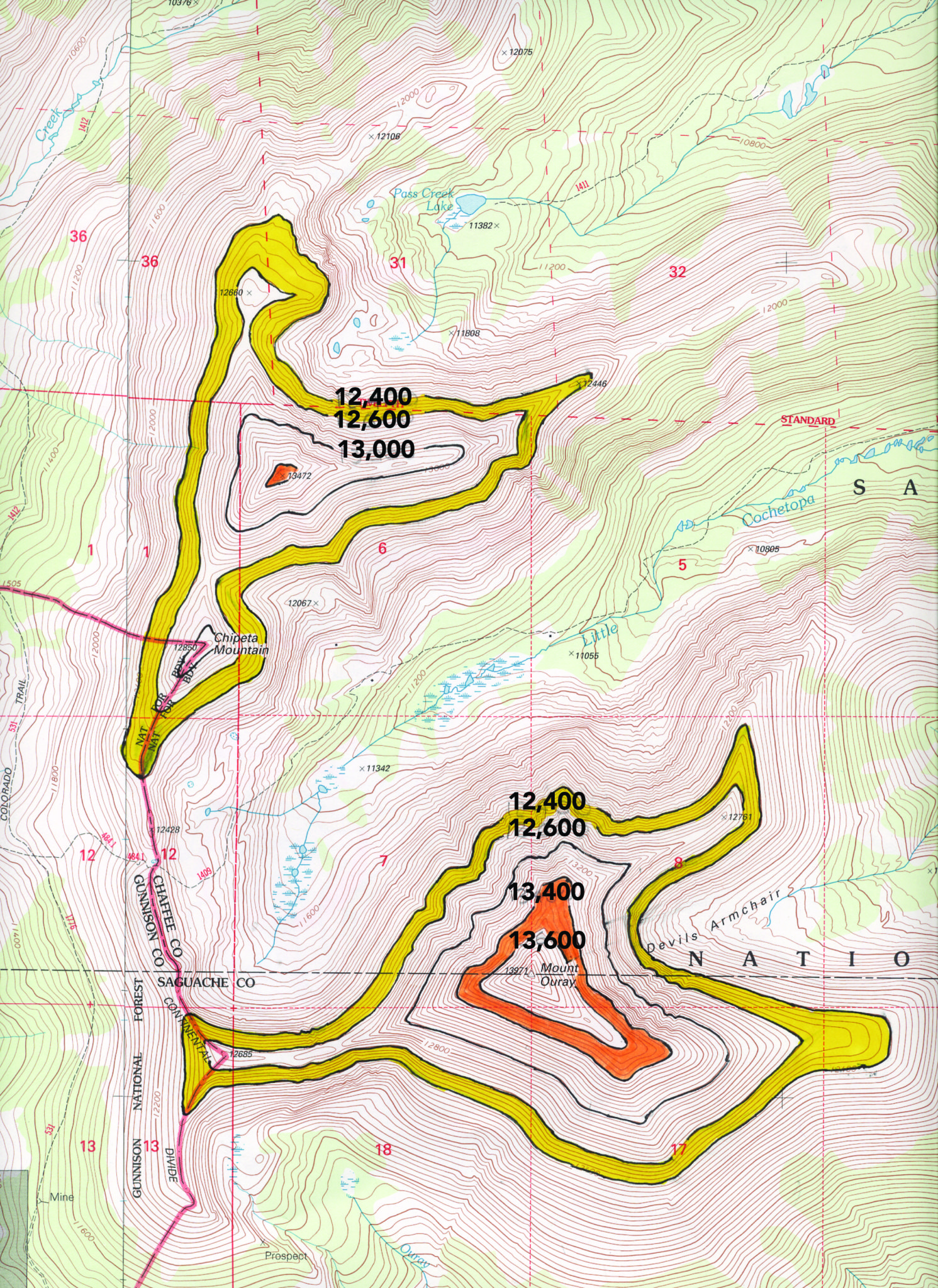

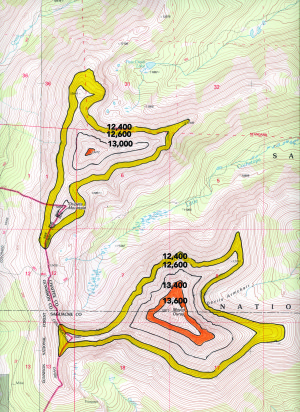

Southern Chaffee County boasts a fabulous view of three mountains in the Sawatch Range named for a Ute (Nuche) Indian family – Mount Ouray, Chipeta Mountain and Pahlone Peak. Indians don’t typically name mountains after themselves, so my guess is that some “white guilt” went into that honor – like a developer who names streets after the trees cut down to build a subdivision. But there is another problem – perhaps an error on the part of the applicant or the U.S. Geologic Survey Board on Geographic Names (BGN). Mount Ouray and Pahlone Peak are named for the highest point on their respective mountains, but Chipeta Mountain is named for the second highest point on its massif and is actually out of plain sight. Thus an effort to commemorate an important woman ends up coming across as more of an insult. So perhaps a campaign to move the name “Chipeta Mountain” from the 12,850-foot sub peak to the 13,472-foot highpoint is in order.

As the famous philosopher Anonymous once said, “An error does not become a mistake until you refuse to correct it.” Hopefully, the BGN will be amenable to the change. Public support will be necessary, so you should know something about Chipeta. She was selected to be on a centennial tapestry created to honor 18 women who played important roles in the settlement and development of Colorado. It now hangs in the State Capitol building.

The most common tale of Chipeta’s origin is this: In 1845, Ute Indians came across an apparently abandoned Kiowa (Plains) Apache camp. On closer inspection, they discovered that a massacre had taken place. Only one person survived – a two-year-old girl who was then adopted into the Ute tribe. They named her Chipeta. She and her husband, Chief Ouray, were known as the Ute Peacemakers. They were married in 1859 – the same year that gold was discovered in Colorado, which immensely increased conflicts between Utes and whites. During their annual buffalo hunt in September 1863, Ouray’s six-year-old son from his first marriage, Pahlone, was kidnapped by the Lakota. Chipeta was heartbroken.

Four treaties were created in Chipeta’s lifetime. In October 1863, a treaty was signed where the Utes ceded their lands east of the Continental Divide. Governor Evans then asked Ouray to settle disputes between Utes and white settlers. Ouray had to travel great distances. Chipeta asked to travel with him, which was unusual at the time. Ouray gained a reputation among white settlers as a fair man. Chipeta was often Ouray’s only confidant. He treated her as an equal. When they went into Ute camps, Chipeta visited with the women and heard how their husbands really felt about matters. Chipeta was allowed in some camps when Ouray was not. She was the only woman invited to Ute Councils.

A second treaty was signed in 1868. It left the Utes with the western third of Colorado minus the Yampa River Valley. Ouray got a house and a salary for being an interpreter. Many Utes wondered how Ouray got such a good deal and speculated that he gave up Ute lands for his own profit. Attempts were made on his life – one by Chipeta’s older brother, Sapovanero. Ouray overpowered him and was about to kill him. Chipeta grabbed Ouray’s arm, commanded him to stop, and mediated a truce between the two.

[InContentAdTwo]

Gold was discovered in the San Juan Mountains and whites clamored for more land. At first Ouray refused, but eventually the Brunot treaty was signed in 1873, and the mineral rich mountains were carved out of Ute territory.

The fourth treaty came because of the Meeker Massacre at the White River Indian agency. It was during this event that Chipeta truly shined. A combination of what Chipeta called “bad Utes” from the White River band and an equally poor Indian agent, Nathan Meeker (who had organized the cooperative agricultural community of Greeley), led to the flare up. Meeker threatened to bring soldiers to the reservation to take disagreeable Utes away. In September 1878, a few Utes stole horses and shot a white man. Governor Pitkin requested military help. Ute scouts saw Army troops marching toward their land from Wyoming and remembered Meeker’s threats. Visions of the Sand Creek Massacre danced in their heads. The Utes ambushed the troops and killed all the officers in minutes. When other Utes found out about the attack, they killed Meeker and the agency men. The women and children were taken hostage.

Ouray, already ill with a kidney disease that would soon take his life, was depressed by this turn of events. He talked about joining his brothers for one last fight against the whites. Chipeta spent the entire night talking him out of this idea. Ouray eventually ordered the White River chiefs to retreat and release the captives. The hostages reported that after they arrived at Chipeta’s home, she did everything possible to make them comfortable.

A formal inquiry into the incident took place in Washington, D.C. Chipeta was named a member of the delegation. Secretary of the Interior Schurz decided the whole White River band had to be punished for the deaths at the White River agency. He assigned them to a reservation in Utah where the Uintah band of Utes lived. He moved the three Southern Ute bands to the very southwest corner of Colorado. He offered the Tabeguache band of Utes a smaller reservation near where the Gunnison River and the Grand (Colorado) River met. Ouray died on Aug. 24, 1880, but the required Ute signatures were collected and the treaty ratified.

The team of men who oversaw the move of the Tabeguache band to their new reservation in 1881 forced those Utes to settle in arid Utah instead of in the Fruita area. Chipeta remarried there and adopted six boys. In 1916, a former Indian agent sent to investigate described Chipeta as “destitute.” Chipeta became a sort of celebrity in her later years and travelled back to Colorado for events and visits. She died in 1924 on the Ouray Reservation in Utah, blind, at age 81. She is buried near Montrose where she and Ouray lived until 1880.

I plan to submit a request to the BGN to “unname” the sub peak currently assigned to her and name the high point of the Chipeta massif after this incredible woman. If the BGN effort is not successful, other tactics can be used. Most Alaskans wanted to rename Mount McKinley and call it Denali – the Athabaskan word meaning “The Great One.” But members of the Ohio congressional delegation used parliamentary tricks to prevent that from happening. President Obama circumvented those efforts last year. U.S. Senators can introduce bills to have place names changed as well. We could go another route.

Chipeta was a member of the Tabeguache band of Ute Indians. Tabeguache is a Ute word meaning “people who live on the warm side of the mountain.” Let’s get this remarkable woman’s name on the warm side of her mountain, not on the cold shoulder.

Check out the website – www.chipetamountain.com – and Facebook page – Chipeta Mountain – to find some ways that you can support this effort.

Bibliography

Chipeta: Ute Peacemaker by Cynthia S. Becker

Chipeta: Queen of the Utes by Becker and P. David Smith

Ouray: Chief of the Utes by P. David Smith

The Ute Indians by Virginia McConnell Simmons

Wayne Iverson lives in Salida for eight months each year and in Alaska for four months. He is the author of the book Hobo Sapien: Freight Train Hopping Tao and Zen. Not many hobos have gone from Yale to rail or from hunk to monk.