By Susan Jesuroga

Beyond the old brick storefronts in downtown Salida and the ghost of the rail yard, long dismantled, there is still one tall and unmistakable symbol of Salida’s industrial past. This sight is familiar to any traveler entering Salida from the north: the 365-foot smelter smokestack.

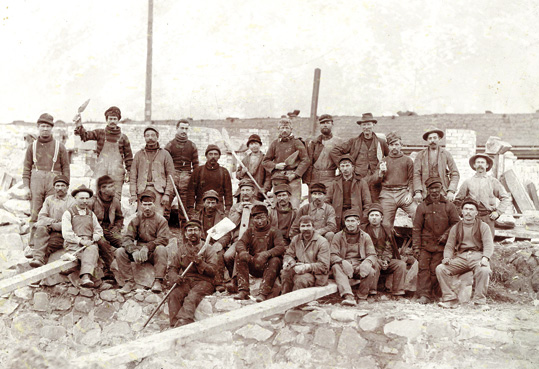

In the late 1800s, Western states saw massive growth in the extractive industries to support the needs of Midwestern and Eastern industries. The increased output from local mines spurred development of the Ohio and Colorado Smelting and Refining Company plant north of Salida. The site afforded access to the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad mainline, availability of ore from the region and ready supplies of fuel. The location also saved money by avoiding the shipping costs of sending ore to the Colorado Front Range for processing. The Ohio and Colorado smelter came online in 1902, covering 80 acres on the banks of the Arkansas River. The railroad also enabled the arrival of workers, in the form of immigrants, hoping to get one of the 400 good-paying jobs at the smelter.

A Salida Record headline on January 1, 1904, trumpeted, “Ohio & Colorado S. & R. Co. Salida’s Great Smelter” and the story boasted that the plant was “the largest and most complete individual precious metal reduction works in the Rocky Mountain region.” Not merely local hype, its importance was underscored in the months leading up to U.S. involvement in World War I. In spite of a general decline in the value of mining production from its peak in 1900, the war brought new demand for lead and zinc, which increased production from many regional mines. On April 27, 1917, the paper reported that a platoon of regular soldiers had arrived in Salida to do guard duty at the smelter. Woodrow Wilson had just asked the U.S. Congress for a declaration of war on April 2, and no doubt the explosions at two munitions factories (Kingsland in New Jersey and another at Chester, Pennsylvania) heightened government fears of attacks on key U.S. industrial complexes.

The 365-foot stack actually appeared much later, some 15 years after the original smelter plant opened. The Salida Mail reported on June 22, 1917, that the stack was “being built to an unusual height in order to provide proper draft.” But most locals knew it was built to mitigate the other output of industrial activity, pollution. (See the article, Standing Tall: A Monument to Environmental Protection in the October 2012 issue.) The tall stack was completed on November 11, 1917. But its use was short-lived. Within two years, the mining industry fell on hard times with the advent of peace in 1919. War demand vanished, and there was a near collapse in all forms of mining activity, wreaking economic havoc on companies and mining-centric towns.

After a fire in 1919, the smelter was leased to another company. The lease did not produce enough revenue, and the smelter closed operations in early 1920. In the months after, many business deals and plans came and went, but the smelter did not reopen and was sold at a sheriff’s auction on October 25, 1920. The smelter was stripped of most of its machinery, brick and other salvage items.

For unknown reasons, the 365-foot stack remained. Chaffee County was given ownership of the smokestack in 1938 when the owner failed to pay taxes. Later, the county sold the land under the stack, but somehow retained ownership of the stack. In the early 1970s, a company crushing mica schist wanted to remove the stack for fear it would fall. A local group called Save Our Stack managed to save the smokestack from destruction. On October 24, 1974, the Salida Museum accepted ownership. In 1976 the smokestack was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

[InContentAdTwo]

The smokestack stands as a proud reminder of the region’s history, and the Museum is hosting a centennial celebration at the smokestack location on August 26 at 10 a.m. They invite you to help honor the smokestack’s place in the story of Salida’s industrial and immigrant past.

Susan Jesuroga is the president of Salida Museum Association.