Column by George Sibley

Labor hisory – August 2003 – Colorado Central Magazine

THE CALLING UP of the National Guard this year, to support the war in Iraq, reminded me that 2003 is the centennial of another occasion in which the Guard was called up in Colorado: in the summer of 1903 Colorado’s troops were summoned for a war — against other Coloradans.

The occasion was a labor strike in the mining districts of Colorado, pitting emerging industrial organizations like the Western Federation of Miners and the United Mine Workers against the established power of industrial giants like the Rockefellers and Gug gen heims.

The reason for the strike? The miners wanted to establish some law and order. Specifically, they wanted the mine owners to obey a state law mandating the eight-hour workday.

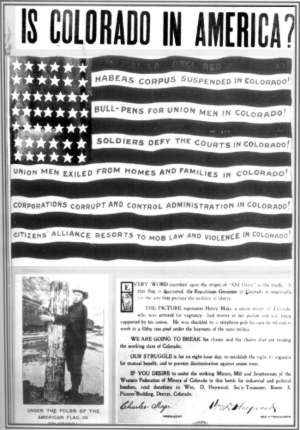

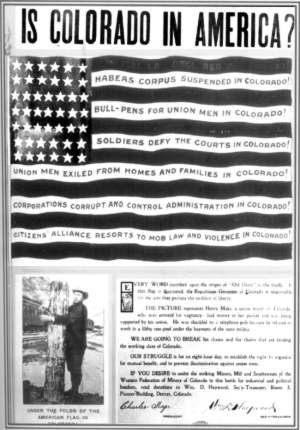

At the time, the standard work shifts were 10 or 12 hours, despite a law the working people had pushed through the state legislature in 1899 establishing the eight-hour workday. But in 1901, the mine owners — the Rockefeller and Guggenheims — had gotten their pocket state supreme court to declare the law unconstitutional. So the miners had gone through the initiative process to amend the constitution, making the eight-hour day constitutional; that initiative had won by some 47,000 votes. But the mine owners ignored the law; hence, a strike.

It was, however, a bad time for a strike. Back in the 1890s, strikes in the mining district had actually been somewhat successful. For one thing, a shortage of miners in the districts had put the mine owners over a barrel; the owners themselves were not organized, and there was a lot of populist strength in the state.

In 1892 Coloradans elected a populist governor, Davis Waite, and he actually called the National Guard out at one point to protect strikers in the Cripple Creek district from the owners and their rent-a-cops — maybe a first, or perhaps an only, in American history.

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) had organized in the Rockies in 1893 and gained strength in those populist years; according to historian Sidney Lens, “In less than a decade, [the WFM] grew from fifteen local unions in five states to two hundred in thirteen states, Alaska, and Canada.” And they built the union’s strength on more than just the organization of workers in the mines; their goal was to organize all of the working people, from the principal industries to the maids and waiters in the service sector, on the assumption that only whole communities could stand up against external money and power.

The WFM engaged in political education, encouraging the miners to read and discuss political history. The miners in Cripple Creek had a library of 8,000 books in their union building by 1902, according to Richard Boyer’s and Herbert Morais’s fascinating book, Labor’s Untold Story. And socialist Eugene V. Debs found them ready for his message of “collective ownership and control of industry and its democratic management in the interest of all the people” when he came through the camps on his presidential campaign in 1902.

BUT A SUBSTANTIAL REACTION began to grow against this unignorable movement toward socialism in America. By the turn of the century the monied factions were stirring in a big way. In April 1902 the mine owners organized a Colorado Mine Owners’ Association (CMOA) which proclaimed an industry-wide policy of refusing employment to any WFM member and, to whatever extent possible, cleansing the state of “that socialistic and criminal organization” through deportations or whatever other means were possible. That November the CMOA and other business interests succeeded in electing a pro-business Republican governor, James Peabody.

To carry out their anti-WFM work, the CMOA helped create “Citizens’ Alliances” in every mining community — essentially vigilante organizations made up of small businessmen and other citizens frightened by the socialist talks who decided they needed the good graces of the owners more than of the workers.

And since the state had no budget for using troops to achieve mine-owner objectives, CMOA members pledged half a million dollars to the state to fund the use of the National Guard to drive out the WFM. Governor Peabody appointed a virulently anti-union former Cripple Creek mine manager, Sherman Bell, as chief of staff for the National Guard.

In February of 1903, the smelter workers in Colorado City (near Colorado Springs) went on strike for a base wage of $3 for an eight-hour day. In August, the Cripple Creek miners joined the strike, followed soon after by the miners in Telluride and the San Juan mining district. And, taking his orders from the mine owners, Governor Peabody unleashed General Sherman Bell and the National Guard.

The war was on — Coloradans against Coloradans.

George Sibley writes, teaches, and organizes in Gunnison, and will continue this story next month.

(Information for this column came from two sources: a wide-ranging paper on “Labor in the Headwaters Region, Past and Present,” prepared by Rod Rogers and Wayne Horman of Gunnison (both former labor organizers) for the 11th Headwaters Conference at Western State College in November 2000; and Labor’s Untold Story by Richard O. Boyer and Herbert M. Morais.)