Review by Ed Quillen

Colorado History – August 2003 – Colorado Central Magazine

Denver from the Bottom Up – Volume One: From Sand Creek to Ludlow

by Phil Goodstein

Published in 2003 by New Social Publications

P.O. Box 18026, Denver CO 80218

ISBN 0-9622169-9-2

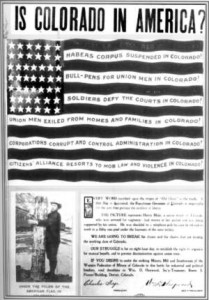

DESPITE THE TITLE, this isn’t really a history of Denver. The subtitle makes that clear, since the framing events, Sand Creek in 1864 and Ludlow in 1914, took place many miles from the city.

Denver from the Bottom Up is actually a history of pioneer Co lo rado with a focus on Denver, and told from a refreshing revisionist perspective.

What is a “revisionist” history? In common parlance — that is, the prose of speechwriters for our current right-thinking president — it means “instead of praising the virtues of the rich and powerful like the standard historians, the historian examines past events from other vantages, and revises history accordingly.”

Those vantages, in Goodstein’s case, include working miners, washerwomen, Indians, prostitutes, small- business owners, hard-scrabble farmers, Hispanics, preachers, agitators, African-Amer icans — that is, the general run of humanity.

But it should be noted that Goodstein does not neglect the millionaires and politicians who star in most histories. This book teems with tales of their shenanigans, all told in a lively and engaging way.

In other words, Denver from the Bottom Up is a lot of fun to read, and I found it filled in many blank places — things I’d wondered about that I hadn’t found much about in other Denver or Colorado histories.

For instance, Colorado was the second state where women could vote in all elections. Indeed, Colorado was the first state where women could vote in any election at all (school elections after statehood in 1876), and the first state to vote to give women the vote. (Wyoming had been a territory when it embraced female suffrage).

But what were the political alliances at the time? Goodstein explains that suffrage was primarily a cause of upper-class reformers who saw it, not as a matter of simple justice, but as the opening wedge to a host of other alleged reforms, prohibition among them.

Thus suffrage was largely opposed by working-class immigrants, who rightly feared that women would vote to close their beer halls. This led to a curious outcome for the Populist party, which captured the governor’s office in the 1892 general election. The Populist leaders supported giving women the vote, but women then voted to turn the Populists out of office. Meanwhile some of the leading suffragettes denounced the “Mexican” voters of southern Colorado.

In other words, this was a political issue that was complicated by economic and social class, as well as culture and gender, and Goodstein explains it thoroughly:

“When the ninth session of the General Assembly convened in January 1893, the Equal Suffrage Association … lacked a regular newspaper or network to get its message across. Nor were many of its members enthusiastic about Populism. Often the wives and daughters of the rich, they tended to look down on Populism as a plebeian revolt; these feminists simply wanted positions equal to those of the men in their lives. By no means did they favor a new society.

“Supporters of the People’s Party were often equally hostile to the feminists, seeing them as spoiled, rich women who fully accepted the status quo.”

Meanwhile, Populist Gov. Davis H. Waite observed “that women had been voting in Wyoming since 1869,” and “their participation in politics had not made any discernible difference there…. Votes for women would not change anything of substance. Consequently, he more or less shunted the issue aside in contrast with Populist goals of shaking up the financial system.”

Even if his support seemed somewhat half-hearted, Waite did endorse suffrage — but women did not necessarily support him. “Middle-class and rich women more or less agreed with ruling Colorado: Waite was a dangerous radical and an embarrassment to the state.”

With this book, you can find out what happened to Coxey’s Army when it tried to march from Colorado to Washington in 1894, or learn the tragic fate of Silas Soule, perhaps the only hero of Sand Creek. You can get all the details about how Colorado got three governors in one day, and marvelous accounts of Denver’s political machine, known then as “the Big Mitt.”

Each chapter has an annotated list of sources, and the book has a useful index — this may be a popular history, but it demonstrates impressive scholarship. Denver From the Bottom Up abounds in neat trivia, like “A gold coin bearing a ‘D’ mint mark in the 19th century denotes Dahlonega [Georgia]. The first official United States gold coins in Denver were not struck until 1906.”

If there’s a “class war,” it’s obvious which side Good stein is on. But like all good writers, he delights in his villains; they may be greedy oppressors of the working class, but they’re also rogues who have engaging stories worth recounting.

Don’t let the Denver title fool you. This is a lively yet scholarly addition to Colorado’s history, and it deserves a place on your shelf if you have any interest in our state’s formative years. No matter what your politics, you’ll find plenty here that you won’t find anywhere else — and you’ll enjoy reading all about it.

— Ed Quillen