By Joe Stone

The Tallahassee Creek area in western Fremont County offers a degree of serenity conducive to a contemplative lifestyle, evidenced by the presence of a monastic retreat on the banks of Tallahassee Creek. This bucolic setting between Salida and Cañon City seemed ideal, not only to the monks and nuns of the Monastery of Our Lady and Saint Laurence, but also to the urban refugees who built homes and hobby ranches in the area during the past 25 years. But what once seemed like the idyllic manifestation of lifelong dreams took a nightmarish turn when residents realized a mining company owned the rights to the uranium that lies beneath their property.Long before anyone lived in the area – a couple hundred million years ago – granite formations created a channel that extended from the Hartsel area south-southeast into western Fremont County. The Echo Park Paleo Channel eventually filled with sandstone through which groundwater flowed. At the upper end of the channel, seepage from precipitation leached uranium into the groundwater. Flowing through the porous sandstone, the mineralized water carried uranium to western Fremont County, where it encountered the carbon remnants of ancient plants. The carbon acted as a mineral trap, creating uranium deposits in sandstone underlying the present-day Tallahassee Creek watershed.

These uranium deposits remained undisturbed until 1954 when uranium ore was discovered. Small mining operations created 16 open pit mines that were eventually abandoned, and in the 1970s, Cyprus Mines Corp. acquired the Taylor Ranch mineral and water rights. In 1981, after drilling thousands of exploratory wells, Cyprus received permits for an open-pit uranium mine and a nearby mill to process the uranium.

The mine would have targeted the largest deposit in the area, the Hansen deposit, containing approximately 40 million pounds of triuranium octoxide ore (U3O8), but the mile-long open-pit mine and 3,000-ton-per-day uranium mill never materialized. In the aftermath of the partial meltdown of a nuclear reactor at Three Mile Island, more than 300 planned U.S. nuclear reactor construction projects were put on hold. The price of uranium plummeted, and mining the Hansen deposit was no longer economically feasible.

Demand for uranium remained low for decades, as did uranium prices. While prices remained too low to support local mining operations, Fremont County commissioners in the ’70s and ’80s knew about the presence of uranium ore but failed to designate the area as a Mineral Resource Area. A 1974 amendment to the Colorado Land Use Act encouraged county officials across the state to do just that in order to avoid incompatible land uses and preserve the ability to develop mineral resources. The 1976 Comprehensive Plan for Fremont County recommended establishing a more definitive zoning plan, and the 1980 Fremont County Land Use Plan made similar recommendations in order to “avoid incompatible land uses.”

But when the 1990 Fremont County Master Plan was published, it designated the “preferred nonagricultural land use” in the area as residential. The 2002 master plan reaffirmed the designation: “The primary nonagricultural land use (in the Mountain District of Fremont County) will be residential” (page 97). “Long-term industrial operations will not be encouraged in the (Mountain) District. … Industrial development should be discouraged along … Fremont County Road 2 (Tallahasee Road)” (page 98), which provides the only access to the area.

Having conveniently forgotten about uranium deposits in the area, county commissioners approved the subdivision of ranch land into large rural residential parcels, benefiting local developers and contractors. Given these master plan statements and a lack of disclosure by developers and real estate agents, residents who bought land and built homes in the area had no idea their investments could be threatened by uranium mining.

By the turn of the millennium, increased use of nuclear reactors to generate electricity, particularly in China and India, led financial experts to predict sharp rises in uranium prices as existing resources began to dwindle. Black Range Minerals, based in Australia, responded by acquiring the mineral rights to 13,500 acres encompassing the Hansen and other uranium deposits and potentially affecting more than 500 residents who had built homes in the area.

Local residents finally discovered the potential for uranium mining in 2007 when they learned that Black Range was conducting unpermitted drilling for test wells. The company eventually obtained a permit but not until after drilling 70 wells, making it impossible for residents to obtain baseline well water samples – the only way they could prove whether or not mining activities would contaminate their drinking water. The lack of oversight and accountability prompted local residents to organize, forming the Tallahassee Area Community group.

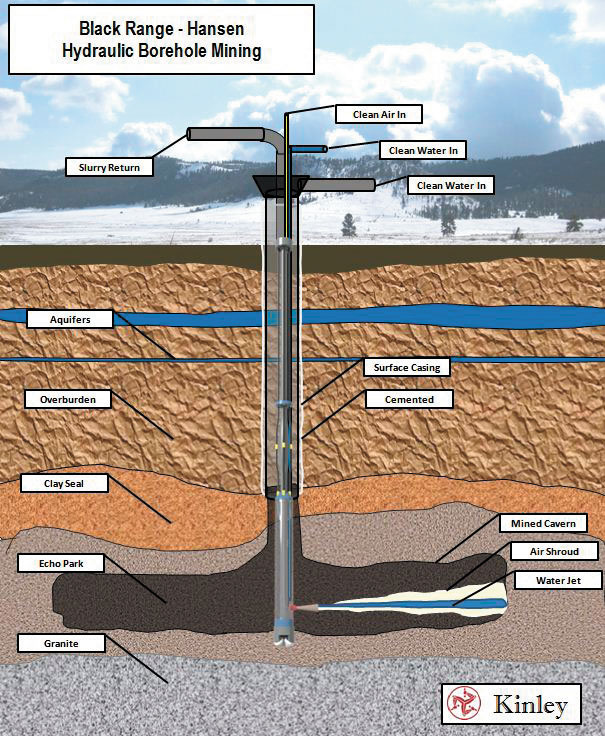

After completing test wells and feasibility studies, Black Range officials announced their intention to pursue uranium mining at the Hansen deposit using a recently developed borehole mining process in combination with an ablation process. Dubbed uranium fracking by opponents, borehole mining uses drilling rigs to sink holes into the ore zone. Once the drill reaches the ore zone, a hydraulic miner is lowered into the ore, where it sends a high-pressure water jet into the deposit, breaking it apart and allowing it to be lifted to the surface in a slurry.

Black Range officials claim borehole mining would have minimal environmental impacts, especially when compared to open-pit and hard-rock mines. After bringing the ore to the surface, Black Range has proposed using ablation to separate the uranium ore from sandstone. Uranium minerals at the Hansen deposit coat grains of sandstone, and the ablation process would separate the ore from the sandstone by firing jets of slurry material at one another. This process knocks the uranium coating off the sandstone, creating concentrated ore.

After separating the ore from sandstone, Black Range plans call for an ion treatment process to remove residual uranium. Following ion treatment, the sandstone slurry would be mixed with concrete and injected back into the ore zone to stabilize the ground. Since not all of the sandstone could be returned to the subsurface, some would remain above ground, where it would be re-contoured into the landscape to minimize visual impacts. After concentrating the ore through ablation, Black Range would then truck the ore off-site for milling into yellowcake at a mill in Blanding, Utah. In other words, the concentrated uranium ore would be transported west on U.S. 50 through Cotopaxi, Howard, Salida, Gunnison, Montrose and beyond.

Once Black Range had announced its plans, TAC members, in accordance with state law, called on county commissioners to disallow uranium mining and ore processing in the area. Fremont County commissioners apparently began to take notice but decided to abandon any pretense of representing their TAC constituents, as indicated by the latest version of the Fremont County Master Plan. Adopted in 2015, the plan echoes earlier iterations: “The primary non-agricultural land use [in the Tallahassee Creek area] will be residential.”

But the very next sentence contradicts previous county documents and attempts to shift responsibility for the situation to the state: “However, mineral resource areas throughout the state are a matter of state interest. The orderly development, exploration, and extraction of minerals is encouraged by the Colorado General Assembly; and such policy and laws related to mining are binding on counties. Consequently, development of natural resources shall be the primary land use in those areas where such resources shall be found” (pages 107-08).

[InContentAdTwo] Residents continue to oppose uranium mining in their community, contending that the ablation process constitutes a uranium processing activity that requires additional permitting. Canada-based Western Uranium Corp., which recently acquired Black Range Minerals, disagrees, and both sides are awaiting a decision from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

Joe Stone is a whisky drinker who enjoys writing about water and environmental issues because whisky is for drinking and water is for fighting over.