By John Mattingly

If you’re like me and many sensible folks in Nevada and Oregon, you’re wondering why the federal response to the Bundy antics has been so patiently executed.

Before pondering that puzzle, I’d like first to state my perception of the underlying problem, for which the Bundys have become icons: The cattle business is not a business today unless it is subsidized by a job in town, an inheritance, an oil well or cheap grazing. Cattle ranching today is a hobby. It simply is not profitable as a stand-alone business, so it goes without saying that it cannot meet the expense of complicated, externalized environmental costs. And finally, feedlot beef, which depends on ranching for a source of feeders, is not healthy food. (In prior columns I have drilled into this claim with some detail.)

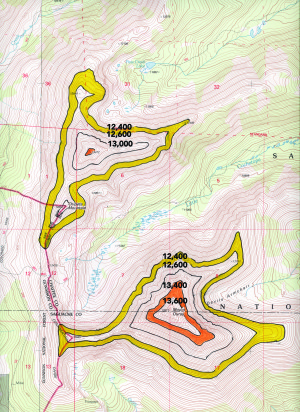

Government-owned rangelands of the West were not homesteaded because they could not sustain a family, so they defaulted to the oversight of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS). These agencies began a progressive, and occasionally aggressive, management regime of public rangelands starting with the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934.

In succeeding years, the demands of citizens other than ranchers and outlaw cowboys for multiuse on public lands emerged along with environmental protections under the Endangered Species Act. These administrative evolutions forced many ranches out of business and forced ranchers who historically relied on cheap federal grazing to face an annoying, and difficult, reality check.

The general rancher mentality is that rangelands are a perpetual grass-making machine: just put cattle out there and hope for rain and you get beef for dinner. Though ranchers are required to have an environmental impact plan for grazing permits, no ranchers using federal rangelands have ever spread an ounce of fertilizer on the range, nor have they given serious consideration to species other than lumbering bovines. The BLM and USFS range cons make determinations as to the number of head that can graze in a given year depending on the condition of the range, but no soil samples are taken, no evaluation of the long-term health of the range is presently reduced to permitting protocols.

While it is true that permittees have built fences, drilled waterholes and made modest improvements to the public range, the spectrum of multi-use demands that ranchers, like Bundy, pay market price for grazing. What could be more in step with capitalist America than that?

As the economic realities of the cattle business closed in on cattle ranchers who utilized cheap federal rangelands, some have tried to claim that the federal grazing lands are actually not federally owned. Bundy, for example, claims the land belongs to Nevada. But he isn’t offering to pay Nevada for his grazing privilege. No, he somehow feels entitled, and that generational sense of entitlement is at the root of much of the anti-government sentiment in the West.

Because the West was such a challenge to settle, what with Indians and droughts and blizzards and lack of infrastructure, cattle ranchers feel entitled to certain privileges for having survived. They ignore that federal troops handled the savages, and federal funds built the railroads and the reservoirs, installed rural electrification and offered cheap grazing and free mining. All of this makes the West one of the biggest socialist experiments in world history, and without which governmental help, bovine husbandry would now be an aristocratic pasttime, like raising large exotic dogs, or baronial fox hunts.

In spite of the enormous contributions made by the feds to the settlement of the West, some Western ranchers like Bundy not only feel entitled to the use of federal lands for free, they point – deaf to the irony – to urban welfare recipients as pikers. And, to top it off, ranchers like Bundy have been granted exceptional latitude for their hypocrisy and their antics.

To wit: Almost two years ago, Cliven Bundy prompted and directed a band of “free” men to use force – as in snipers and armed formations – aimed at BLM and other federal agents who came to the Bundy ranch to repossess his cattle for non-payment of grazing fees.

[InContentAdTwo]

The feds stood down in that conflict, avoiding a firefight that likely would have required a massive show of federal force that would have been bloody and messy while showing the “free” men who the real men were; but would have risked creating martyrs and accusations of overkill, such as happened at Waco or Ruby Ridge and other times when the feds simply overwhelmed anti-government militias. Too, the feds determined that, in this case, a firefight would not, and indeed could not, resolve the anti-government issues at stake. Isolating the protesters, and building a strong legal case, were determined more effective than achieving a short term tactical victory.

But nothing happened to Cliven after the feds stood down. For two years he continued to run his cattle without paying grazing fees, and his militia men went around claiming victory, never suspecting that they were actually in the eye of the hurricane they had created. Some of us following this case wondered if Bundy was, somehow, above the law.

The lack of consequences for resisting the feds at Bundy’s Nevada ranch may well have emboldened Cliven’s sons Ammon and Ryan to occupy the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Harney County, Oregon. The rationale for this occupation initiated from the divine: Ammon heard directly from God that he was to do this, as he tearfully explained in a YouTube video in early January of this year.

Once underway, the Bundy Refuge occupation was to gain leverage for the release of convicted arsonists, the Hammonds, fellow cattle ranchers who depended on public rangelands who were in prison for setting fires on those rangelands but who wanted nothing to do with the Bundys; and in part, the occupation was a protest against government overreach – the latter being a vague mantra of various militias who think their country has been taken away from them by bureaucrats, potlickers, a black president, welfare queens, gays and assorted liberals who want their guns.

At bottom, the rationale for occupying the Refuge never became as clear as Cliven’s straightforward resistance to paying his bills, and the conduct of the occupiers did not inspire. Twitter pleas for cigarettes, energy drinks and candy bars made many of us wonder if their next request was going to be for their mothers to come in and do their laundry. One of the occupiers, Lavoy Finicum, sat in a chair, rifle across his lap, covering himself with a blue tarp, uncovering himself occasionally to speak to the press to make it clear that he was not going to prison, speaking poetically about his abiding need to feel the wind on his cheeks.

Despite the obvious spinelessness of the Refuge occupation under the leadership of the Bundy boys, the feds were not provoked. The occupation went on for almost two months before the feds closed in, first with a roadblock that caught the Bundy brothers and several lieutenants of the occupation, and later with the gradual, bloodless and cowardly capitulation of the scattered remainders. One protester was killed: Lavoy Finicum, the man under the blue tarp, who lived down to his word.

The strategy of the feds is now clear. They did not want to risk a firefight by arresting Cliven on his 160-acre ranch, so they waited until they could make the arrest on territory they could control. Similarly, they gave the Refuge protesters latitude to express all their grievances, most of which vacillated between incomprehensible and comical.

Here’s the hammer: The complaint against Cliven Bundy, 69, filed simultaneously to his arrest last week, charges him with conspiracy to commit an offense against the U.S., assault on federal law enforcement officers, carrying a firearm in relation to a violent crime, and obstruction of justice and interference with commerce by extortion. In other words, they threw the book at him. Cliven faces up to 30 years in prison and fines approaching a million dollars, in addition to the back grazing fees of that amount. The same battery of charges face Bundy’s boys, and to some extent others involved in the Refuge occupation.

But we don’t know how much of this will stick. The feds did not take the bait and engage the protesters in violence that might have confirmed the protesters’ claims of overreach. Instead, the feds withdrew, taking the time needed to build a solid case, while allowing the protesters to burn out. Now the feds have to finish the job and prosecute.

We have to wonder if this strategy of lay-low-and-build-a-case suggests a change in the Department of Justice (DOJ) toward more effective prosecutions, guided by the new attorney general, Loretta Lynch. Under Eric Holder, we did not see effective prosecutions in Wall Street fraud cases, or high profile environmental disasters like the Gulf oil spill, or the methane gas leak in California, where criminal acts were obvious but paid off with civil fines. Currently under way are DOJ cases in Ferguson, Missouri, Chicago, and possibly Flint, Michigan that will reveal more about DOJ policy.

In particular, the failure of the DOJ to prosecute Wall Street fraud can be understood in the context of the skills and disposition of former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder.

When Obama came to office in 2009, he appointed a group of Ivy League defense attorneys to the DOJ. Holder came from one of the East Coast power defense law firms, Covington and Burling, the firm that had previously defended the likes of Wells Fargo, Citibank and AIG, among the most egregious players in the financial meltdown. It was not surprising that Obama’s incoming DOJ had no experience with complex prosecutions and had some early, high-profile failures (Ted Stevens). The result was a timid DOJ stacked with defense attorneys who put more emphasis on not losing than on winning when it came to criminal cases. Instead of prison time, white collar criminals paid fines, which has become no more than an added cost of doing fraudulent business.

Too, the DOJ was concerned in the years immediately after the financial crisis that prosecutions might cause the markets to further decline, just as the feds now take their time with criminals like the Bundys for fear of generating backlash disturbances among the harebrained militias.

When Holder resigned, Loretta Lynch (eventually) took his place. She is a prosecutor. Whoever wins the White House will have some influence on DOJ positioning. It may become robust, or we may see more of the shrewd and patient prosecutorial competence witnessed in the handling of the Bundys. For that reason, keeping up with the Bundys – the lame Clydesdales of the anti-government team – has been revealing as to the current tenor, disposition and direction of the DOJ.

And finally, the emergence of the Bundys as spokesmen for the John-Locke-run-amock constituency in the evolving policy battles in the West reminds us that success in getting out a set of ideas, grievances or ideologies in today’s celebrity-obsessed culture, requires first that one become a public personality. Cliven Bundy did it. From his quirky name, to his stylish, starched western wear, to his big hat, to holding a dead calf in his arms, to opining that blacks would be better off picking cotton … all he had to do was open his mouth and Americans, predictably fascinated with the willful self-delusion of celebrity, wanted to hear what he might say. For fifteen minutes.

John Mattingly cultivates prose, among other things, and was most recently seen near Poncha Springs.