Column by Hal Walter

Agriculture – July 2008 – Colorado Central Magazine

RECENTLY, AFTER BUYING an eighth of a beef from a neighbor, it occurred to me that if the price of fuel drives me to eat poorly, then I might be better off crawling into a hole and pulling the dirt back in over the top.

This is a weighty question for someone who chose long ago, when gasoline and food were still relatively cheap, to live 15 miles outside a small town and 50 miles from the closest city, or at least something that approximates one, like Pueblo.

I suppose it shouldn’t be surprising when we invite an oil company to run our country that its operators would squeeze us for every last penny on their way out the door.

Consider that many of us will use our “Economic Stimulus Tax Rebates” to offset the high price of fuel; essentially we’ll be taking money the government is borrowing and handing it straight over to oil companies that are posting record profits. It could be a new definition for insanity. Also, theft.

The beef I bought didn’t require much gas. The steer was born about three miles from where it died. It was then carted 15 miles to town where it was processed, and came back home to a freezer. Including local hay, which was trucked as winter feed for the animal, it would be reasonable to guess this forage-fed steer had less fuel in him than occupies the average SUV tank at any given time.

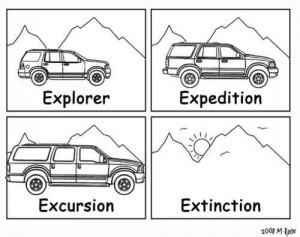

Compare that to an animal raised in a feedlot and fattened on corn. Experts say animals raised in this manner take as much as a half-gallon of gasoline or equivalent petroleum fuel for each pound of beef produced. That’s a lot of fuel tied up in steaks and burger.

Why is this so? Conventionally raised cattle have to be shipped by truck to feedlots. Meanwhile farms must raise energy-intensive corn to feed these cattle. Farmland must be cultivated and planted, and the corn is often treated with petroleum-based fertilizers. Additionally, pesticides are often applied by means of crop-duster planes.

Once it’s ripe, corn must be harvested, then taken to a depot, then to a grain mill where it is often steam-treated, rolled or ground. From there the grain is routinely transported to a silo and stored before being shipped to the actual feedlot. At the feedlot, internal combustion machines are employed to feed this grain to the cattle. Then the cattle must be shipped again to the slaughterhouse.

This beef that I bought locally cost about what I spend to fuel my truck for a month. It never ate any grain, and was never given any drugs or hormones.

It is an irony that I am buying beef at all. When I am not at this keyboard my other job is ranch manager for a natural grass-fed beef operation. For the past three years all of our meat animals have gone for paying the winter feed bill, and I have not seen so much as a hamburger. This year it’s shaping up to be a little different. We have some steers readying for butcher, and I recently talked the owners into buying a few extra animals.

I arranged to buy these clean cattle from Randy Lawson in Wetmore. It was a package deal I put together with two steers and a big 1,240-pound 3-year-old open heifer for us, and two yearling heifers for my neighbor Peter Hedberg — five head total.

Peter recently secured the grazing lease on the Dilley Ranch subdivision, where he won’t mind my saying that he and his trophy-homer neighbors are dodging property taxes by providing cheap grass for his cows. At least this time someone I like is getting that cheap grass.

EARLY ONE Sunday morning Peter and I went down to Wetmore and took delivery of these cattle, and brought them back up here, a 40-mile round trip. We stopped at the school section, where my herd is, to sort Peter’s from ours. There’s an old corral that I have jury-rigged with some steel corral panels for sorting and loading. It’s certainly nothing fancy, but it works. Usually.

Everything was going all too smoothly when the most bizarre thing happened. One of the steers climbed out of the corral, onto the county road, and then ran up the steep hill to the north. There’s a fence corner at the top of the hill that borders Bear Basin Ranch. The steer slipped through the fence just downhill of this corner and simply vanished.

I figured this steer would want to return to his herd, so I decided not to chase him any farther on foot right then. I went home for a snack, then saddled Redbo the saddle donkey and spent a good part of the afternoon running, riding and hiking but not finding this steer. I finally had to quit to go to a graduation party. Later, Peter came over on horseback and rode all through the area looking for the steer, but he was nowhere to be found

I went out the next day and combed the entire area again but could not find any sign of the steer. The animal was simply gone.

On Monday evenings I am the night city editor at the Pueblo Chieftain. While I was down the hill, a neighbor called and said he’d seen a black steer over in Ilse (pronounced “Ill-see” ) Camp, which is a couple of miles in the opposite direction from where the steer had run.

Tuesday morning, still groggy from a night of bad syntax, I went over to Ilse Camp, which is a subdivision of upscale homes, and found the steer in an aspen grove in some steep hilly country on the eastern end. I started hazing him back to the west on foot with Sam, my new dog, helping. But at the top of a hill the steer started trying to turn on us and finally galloped right back to where I found him.

WHEN I GOT BACK to our original starting point I tried to get him to move along a fence and he just went through it and kept on going. I followed at a fast march and sometimes at a jog. He went through a couple more fences, heading for another neighbor’s ranch. He was also heading in the general direction of Wetmore.

At one point I was chasing him up a hill and looked up to see a huge longhorn bull standing at the top and looking down at me. This sort of thing tends to get a person’s attention. The longhorn turned and went with the steer, and they ended up along yet another fenceline with more cattle on the other side. The last I saw of the steer he was galloping up the valley with the longhorn bull following him on one side of the fence and several dozen corriente cattle running on the other.

I opted to jog the few miles back to my truck, and called the neighbor to tell him that I had a steer in with his cattle. He said it was no problem, and that the steer could stay there until he calmed down and we figured out a way to get him corralled. I was a little bit concerned because I knew the steer was only a couple of fences from Colorado 96, which could put him back home in Wetmore in short order. But three weeks later, the steer is still there.

It’s not easy to raise your own food, which is probably why most people just go to the grocery store. For many items, it’s a necessity; for instance I don’t see any coffee trees growing in this neighborhood. But I’m trying to strike a blow against factory farming by getting at least some of my food from unconventional sources. I recently purchased a dozen laying hens and have found great joy in collecting four to eight eggs daily. Today I picked arugula from my garden. I put in for a deer license this year. And I’m eating beef raised on grass, not gas.

If you aren’t eating well, you’re not living well. Don’t be fueled into thinking otherwise.

Hal Walter raises and races burros, among other things, in the Wet Mountains.