Vino Salida

By Ann Marie Swan

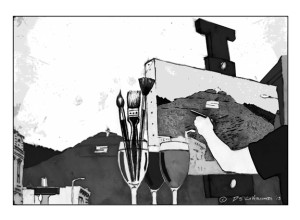

Heaven is a place where Salida winemaker Steve Flynn can follow his calling as an artist. He’s created Vino Salida Wine Cellars with a spiritual vibe where he can get into a focused zone, taking chances while concocting unique, tasty products. “The winery is my art studio,” Flynn said. “I get cranky when I don’t make wine.”

Flynn’s patron saints, high on the walls, watch over him as he works. San Vicente, the patron saint of winegrowers, is in the house, along with Saint Bernard, the saint for skiers and, hopefully, apres ski activities, which could include wine. Because wine is paired with food, Saint Lawrence, the saint for chefs, stands guard. Perched above are statues of Buddha and Jesus, who did, after all, turn water into wine.

“We need all the help we can get,” said Flynn in his funky, bright space with canyons of wine barrels and boxes.

Divine intervention aside, Flynn attributes his success to close, personal relationships with friends, customers and grape growers. Some of these bonds began in his backyard grape-stomping gatherings, starting in 2004. Friends pitched in to buy grapes, bottles and corks. Flynn then rolled up his sleeves and went to work.

Flynn’s grape stomps recreated the winemaking parties of pioneer Italian families in the Upper Arkansas Valley. It didn’t take long before they became renowned. In 2009 Flynn produced his first commercial batch of community Merlot wine, Smelter Stomp, a nod to his previous location in a historically industrial area on the outskirts of Salida.

Neighbors, dear friends, acquaintances and party-crashers turned out on glorious fall weekends to de-stem tons of grapes, building a high purple berm.

Grape-stompers then stepped into a bleach solution before getting into bins of whole grapes. Children and adults alike squealed as the grapes squished between their toes, splattering purple dots. Flynn’s product became a true community-infused wine.

“It’s what makes us unique,” he said.

Flynn’s close relationships with growers in Palisade and Paonia have reaped an unexpected bonus – a competitive advantage. Their words and support have been invaluable. Flynn pays close attention to the weather’s yearlong effect on grapes. Spending time in the vineyards, pruning, counting buds and assessing soil conditions have contributed to his education.

The experience comes full circle when Flynn brings his wine to share with growers, hoping it will taste sublime and gorgeous.

Knowing what’s going on in the vineyards gives Flynn insight into how to gauge his bets, such as gambling on mead. Flynn made mead during a shortage of grapes in 2010. Rather than ordering all of his grapes from California, Flynn looked in his neighborhood for opportunities and purchased local raw honey for the mead from fourth-generation beekeeper Jamie Johnston at Beeyond the Hive. This risk paid off with three different meads, the most popular a traditional, semisweet honey mead, BeeVino 2011.

Local connections keep circling back toward Flynn, bringing in more abundance. In 2012 Flynn collaborated with Deerhammer Distilling of Buena Vista, supplying wine for a highly successful oak-aged brandy, Buena Vista Brandy. Later, Vino Salida took Deerhammer’s clear brandy, Eau de Vie, and added it to a fermenting Syrah for a port-style wine named LaVell after Flynn’s wife’s father. Notes of dark cherries, golden raisins, brown sugar and rich oak make this wine a favorite. It’s got a kick, too, with 18.3 percent alcohol.

Recently, Flynn hooked up with P.T. Wood of Wood’s High Mountain Distillery of Salida to make vermouth and brandy. They’ll distill Flynn’s wine to a base spirit infused with botanicals. This concoction will then be added back to the wine, bringing up the alcohol content of the vermouth to 18 percent or more. “We’ll do a dry, a mid-sweet blanc and a vermouth done red,” Wood said.

Flynn doesn’t know of any other winery in the state working on vermouth. “We’d be the first,” he said.

Next, Flynn will make wine specifically for brandy. “I realized fairly soon a distillery is a winery’s best friend,” said Flynn.

Flynn tends his fragrant purple drink in his uniform of bright yellow overalls, endearingly seasoned with rips and wine stains, and black boots. He talks about gently steering the fermentation, expressing what the grower has done. To complete a wine lush’s fantasy, he pours samples.

Flynn starts with his 2011 Dry Riesling, saying he’s doing something different with this one. This riesling won a bronze medal at the 2013 Governor’s Cup, a Colorado commercial winemaker competition. We move on to Mo’ Sweet, a Gewürztraminer, co-fermented with riesling on its natural yeast. “Some wines take off, and this one did,” he said.

Next up is a 2011 Cuvee Rouge, a blend of Colorado red grapes, which won a silver medal in the 2013 Governor’s Cup. “Every year has its own wine,” Flynn said.

Another standout wine is the 2011 Tenderfoot Stomp Merlot, a 2013 Governor’s Cup silver medal winner. At the same competition in 2011, Vino Salida brought home three bronze medals for its 2009 Viognier, 2009 Syrah, and 2010 Tenderfoot Stomp Merlot.

Vino Salida has more than 60 accounts with restaurants and liquor stores, distributing to the Front Range, Western Slope and mountain towns in between.

Flynn’s web of support becomes stronger all the time with more connections. Vino Salida signed on in May as the wine sponsor for Salida’s 2013 FIBArk Whitewater Festival in June.

“Interpersonal relationships are huge, unless you want to be faceless and impersonal,” Flynn said. “That’s not what we are. We want people to know we are friendly and will take the time and treat them special.”

Vino Salida, 8100 U.S. Hwy 50 Salida, CO 719-539-2674 www.vinosalida.com. Hours: Monday through Saturday: 10 to 6, Sunday 12-5

The Winery at Holy Cross Abbey

By Mike Rosso

In 1886, two Benedictine monks came to Breckenridge, Colorado from St. Vincent Archabbey in Latrobe, Pennsylvania; other monks soon followed. In 1924, they established the Holy Cross Abbey on 200 acres at the eastern edge of Canõn City. Among the things they had in mind was a possible summer home for the Pope. When the Vatican put the kibosh on that idea, the monks began a boarding school for students that lasted until until 1985.

Fast-forward to 1998, over in Palisade, Colorado, where an unnamed businessman was building a new winery and having difficulties with some construction issues. He decided that an exorcism might be in order and contacted Bishop Arthur Tafoya in Pueblo requesting assistance. Help arrived in the form of Father Paul Montez, who apparently was successful in the exorcism. Father Paul then decided a winery might be a good way for the Benedictine Society to help the struggling Abbey raise funds; with the assistance of California winemaker Matt Cookson, they opened the Winery at Holy Cross Abbey in 2002.

With an aging population of monks, and facing economic difficulties after closing the school, the Winery was sold in 2006 to Larry Oddo, who moved to Colorado from the east coast to take over operations. He kept Cookson on as the chief winemaker, purchased the name from the monks and expanded the production, with the Benedictines continuing to receive returns on their investments.

The Winery sits on property that once belonged to Captain Benjamin F. Rockafellow who ran it as Fruitmere Farm, producing apples, pears, grapes, cherries, alfalfa, clover and hay. He sat on the CSU Board of Agriculture from 1921-22. Fremont County saw an agricultural boom in the late 1800s, providing a food basket for regional mining communities such as Cripple Creek, Victor, Westcliffe and Silver Cliff. Fremont County was the first to begin the cultivation of wine grapes in the state.

The farm was also once part of the state prison system. The Colorado Packing Company (the prison cannery) operated on the premises for a number of years.

The tasting room for the Winery was built by Percival Hamilton Troutman in 1911, who owned a strip of land just east of Rockafellow. He incorporated elements of Japanese architecture in the design. For years, the space sat abandoned and unused, except for a few stray cats and a ghost named Billy, who, according to Cookson, “is an 18- to 20-year-old who messes with stuff.” Today, it is a fully restored tasting room, offering wine tastings, retail wines and other wine accessories such as wine racks, glasses, openers and more. The house overlooks a one-acre vineyard of Riesling grapes planted from rootstock ten years back.

The actual winemaking operation is in an old auto shop behind the tasting room and according to Cookson, is cooled by a “Colorado hillbilly humidity control system.” In other words, it’s a swamp cooler which maintains the room at a 65-70 percent humidity – ideal for barrel aging. Cookson’s assistant is Jeff Stultz. In addition to his winemaking duties, Stultz also grows Norton grapes, a rare American hybrid, along with some Riesling vines on land that he, his wife and his parents own along the Oak Creek Grade. At 6,800 feet, it could very well be the highest vineyard in North America. The staff at the Winery increases during bottling season, employing mostly rafting guides looking to make some extra cash and maybe bring home a bottle of wine.

Winemaker Matt Cookson graduated from Fresno State University in 1984 with a degree in Enology—the science of wine and winemaking. Fresno State is the first college in the nation to operate a commercial winery, and students are engaged in all aspects of the winemaking profession. Cookson moved to Colorado in 1999 to help start the Winery at Holy Cross Abbey; and, with a grin, he also claims a “master’s degree in barrels.” The Winery uses primarily American oak barrels from Missouri for aging and fermentation. The barrel interiors are “toasted” before use over a fire pot, which helps to release sweet and vanillin overtones. Cookson describes these as “high notes” which eventually fade after a few years of use. The barrels then tend to impart more of a woody flavor. The barrels actually breathe, interacting with oxygen to help break down the tannin structure; this helps to soften the wine as well as create flavor. These tannin structures “caramelize the sugars and bring out the sweetness in the wood,” explains Cookson. Keeping these barrels in rotation helps maintain a consistency in the flavor.

Grapes for the Winery come from California as well as Colorado sources on the Western Slope and surrounding Fremont County. The Winery is also the largest purchaser of grapes from Colorado Correctional Industries Juniper Valley Farms Vineyard outside Cañon City. The Winery produces between 12,000 and 14,000 cases annually, with many of its customers within a 150-mile radius, including Pueblo, Colorado Springs and Fremont County. In its first year of operation, the Winery processed 30 tons of grapes. That number shot up to 120 tons the following year and is currently at its full capacity of 200 tons annually.

“We tried to create a community type of winery right out of the chute,” explains Cookson. This is evidenced by their very popular Wild Canyon Harvest wine, one of the hottest-selling wines produced in Colorado, made up almost entirely of grapes harvested from the backyards of Fremont County and a few Pueblo County residents; it is released six or seven days before Thanksgiving. The release traditionally occurs the day before the domestic release of French Beaujolais, “just to annoy the French a little bit,” laughs Cookson. This year they celebrate the 11th anniversary of the Harvest Festival on September 29 and 30. It will feature artists, local foods, entertainment and of course, wine. The winery also offers its wares at the Crestone Music Festival, held in August each year, where they have had a booth since 2006. “It’s just a great time,” says Cookson.

The Winery at Holy Cross Abbey has produced many award-winning wines over the years. They received Double Gold awards for their 2010 Syrah at both the 2013 Tasters Guild International Wine Competition and the Colorado Governor’s Cup Wine Competition. Their 2010 Merlot was named Best New World Merlot at the 2013 Jerry D. Mead New World International Wine Competition. One of Cookson’s primary goals as a winemaker is to “make sure the wine that goes into the bottle is good, because there is no turning back after that … you’ve made that commitment.”

Several varieties of the Winery’s gold medal wines were sampled as part of this interview; be assured that Cookson and the Winery are committed to producing the best possible wines in the shadow of the former monastery. The monks would be pleased.

The Winery at Holy Cross Abbey, 3011 E U.S. Hwy 50, Canon City, CO, 719-276-5191, Toll-free: 877-422-9463 www.abbeywinery.com. Hours: Monday through Saturday 10-6; Sunday: 12-5

Mountain Spirit Winery

By Tyler Grimes

If you turn off U.S. Hwy 50 on to County Road 220 west of Poncha Springs and make an immediate left on to a dirt road, you’ll find yourself under the arching branches of old trees, passing fence-lined picturesque meadows in the shadow of surrounding hills. If you continue on, a homestead appears on the right, complete with a wooden-railed fence, a small orchard, abandoned farmhouse, old wooden sheds, decaying farm tools and even an original outhouse. Once on the property, a gently passing stream and chirping birds greet your arrival. Amidst the farm locked in time, one piece of modernity stands out – a large metal warehouse. Making your way inside, you’ll find an operating-room clean facility with rows of tall fermentors. This vintner’s paradise is Mountain Spirit Winery.

“Winemaking requires a very sterile environment,” says Michael Barkett, owner of Mountain Spirit. Barkett, or as his patients and colleagues know him, Doctor Barkett, founded the winery with his wife, Terry, in 1995. Both of the Barketts’ occupational backgrounds were in biology, so keeping a clean working environment comes naturally. “Cleanliness is key,” the doctor reiterates: “If a winery is dirty, walk out.” That’s because once bacteria has found its way in, it’s nearly impossible to get out, and if it gets in the bottle, the wine is ruined.

The couple moved to actualize their lifelong dream after attending Colorado Mountain Winefest and learning of the industry boom. When it opened, Mountain Spirit was the 13th winery in Colorado; there are now over 100. One of the first challenges for the Barketts was finding a location, and a five-acre property bordering their ranch became available. The site was a former chicken farm. All of the original structures are still intact except the old coop, which was replaced by the warehouse. The outside of the farmhouse is in good condition, but the inside has aged and is no longer functional for anything other than storing empty barrels.

The Barketts learned winemaking by taking a viticulture class from the University of California Davis and from other wineries willing to help. A few individuals in particular helped the Barketts grow from wine enthusiasts to wine producers: Jim and Ann Seewald, founders of the Colorado Wine Industry; and Matt Cookson, of the Winery at Holy Cross Abbey.

Colorado-grown fruits and an ideal producing environment have contributed to Mountain Spirit’s success, and they have been recognized worldwide. The winery has won over 50 awards since it opened, with the Angel Blush, a best seller, winning gold multiple times at competitions like Amenti del Vino International. Most recently, the Angel Blush won silver along with Sophie’s White, and the Merlot/Raspberry and Blackberry/Cabernet Franc took bronze.

Currently, Andrew Ritchie, head winemaker, is letting time put its touch on a Cabernet Franc, which will be ready for bottling in a few months. He says there are a few people who have the “difficult job” of tasting wines during fermentation and determining when thery’re finished. The most recent product to be finished was a Zinfandel; Ritchie said he drank it all winter and slowly witnessed it improve with time. The Mountain Spirit vintners are constantly experimenting with new ideas and trying new things, but most of what’s bottled are old concoctions. “All of the wines are from Dr. Barkett’s original recipes; I just put them together,” said Ritchie, son-in-law of the Barketts.

In his free time from mixing grapes, Ritchie, owns and operates the Twisted Cork Café in Salida. Or perhaps it’s the other way around. “This is stress-free compared to the restaurant,” said Ritchie while preparing for a future bottling. He and the Twisted Cork have partnered with the Barketts to make Mountain Spirit wines more easily available by opening an art and wine gallery adjacent to the Café. In fact, the gallery is the only other place to buy Mountain Spirit wine outside of the winery.

Mountain Spirit Winery finds unique ways to distribute wine other than stores. Members of the Mountain Spirit Angels wine club, a group of over 400 people, have two bottles shipped to their homes quarterly. The club is free to join and gives members discounts on wine, merchandise and artwork. The winery relies on volunteers to help bottle new wines, which happens about eight times a year, compensating their labors with free wine.

Dr. Barkett meets me in the evening after seeing patients all day to tell his story and the history of Mountain Spirit. He points out a pile of grape skins behind the warehouse and explains that winemaking is an “ecologically positive” industry. The trait evident in his personality, no doubt formed from years of practicing medicine, is the imprint found in his winery that trickles down into every bottle: attention to detail.

Mountain Spirit Winery, 15750 County Road 220, Salida, CO. 719-539-7848. Tours of the facility, given by winemakers, are offered seven days a week during the summer. www.mountainspiritwinery.com