Article by Duane Smith

Colorado History – August 2003 – Colorado Central Magazine

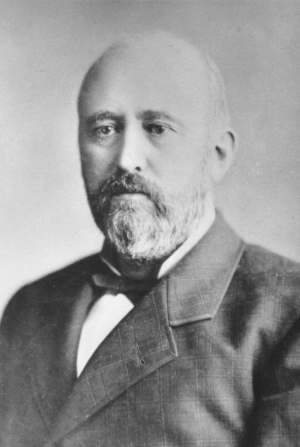

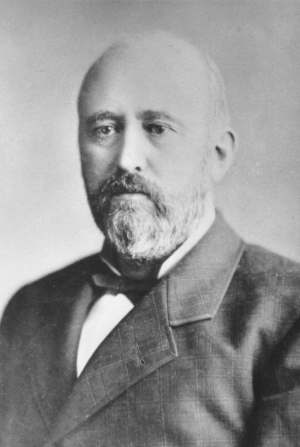

JEROME BONAPARTE CHAFFEE — mining man, politician, businessman, mill man, banker, and one of Colorado’s first two senators — was a “mover and shaker” in the 1860s and ’70s. Yet he quickly receded into history after his death in March 1886.

Yes, there is a Chaffee County today — and once there was a Chaffee City, which was renamed Monarch, after the district’s most prominent mine. But not much else remains to remind the visitor and newcomer that Jerome Chaffee helped direct Colorado’s destiny once upon a time.

Many of Chaffee’s contemporaries are better known; take Henry Teller and Horace Tabor, for example. There is even some debate about how to pronounce Chaffee’s last name; is it a long “a” or a short “a”? For someone who was once “Mr. Republican,” a famous and wealthy mining man, who was literally the “boss” of his party, this seems an unkind fate. Or was it?

Born in Niagara County, New York on April 17, 1825, Chaffee’s early life reflected the story of westward migration. His parents moved to Michigan and then young Jerome traveled to St. Louis where he entered the banking business. The lure of the Pike’s Peak country brought him west in 1860, and he became partners with Eben Smith in mining and milling operations in Gilpin County. At the time, Central City and Gilpin County were the shining lights in Colorado mining.

Smith became a noted mining man over the next few decades, and proved to be an excellent choice for a partner. Together he and Chaffee made “handsome fortunes,” in mining and milling gold according to one contemporary.

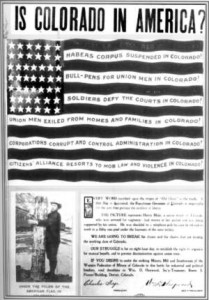

Chaffee’s Bobtail Lode became involved in Colorado’s first miner/owner conflict. The miners didn’t appreciate being paid in inflated paper money rather than gold, and they demanded shorter hours, too. The miners took action in April 1863, but the strikers returned to work, having gained nothing. Chaffee learned from the experience, however, and there was little labor unrest in his other mining ventures.

Straying further afield, Chaffee became involved in the speculation over the Maxwell Land Grant which covered more then a million acres in southern Colorado and New Mexico. He entered the scene in 1867, as the head of a company that bought the grant for $750,000. They sold it to an English syndicate for $1.3 million, and for the next century and more, the fight was on as to who owned what and where. Although Chaffee was not personally involved in the long legal dispute, the pattern for his career of buying and selling had been established.

IN A LESS SPECULATIVE VENTURE, Chaffee used his Gilpin County money to organize Denver’s First National Bank, which emerged initially as the territory’s, then the state’s, leading banking establishment. During this endeavor, bank president Chaffee became friends with another New Yorker, David Moffat, a director, and the two became partners in various mining deals in the following years.

But Jerome Chaffee chose to live in the territory’s major city and its political heart, Denver, not in the mountains — and mining merely served as the base for his further adventures. Chaffee was a spectacularly successful miner and banker, but he really came to prominence in politics, where he exhibited “remarkable talents,” according to a contemporary, Frank Hall.

He did indeed.

After the trials and tribulations of the Civil War, many Coloradans decided the answer to their problems lay with statehood. In 1864, the movement commenced, spearheaded by Denverites, including John Evans, William Byers, John Chivington, and eventually Chaffee. They became known to their opponents as the “Denver Crowd.”

Fortunately for them, the Union Party (as the Republicans called themselves during the Civil War) was unsure that they could win the presidential election that year. So to entice votes, they offered Colorado, among others, statehood.

The pro-staters enthusiastically and quickly called a constitutional convention, wrote a constitution, and nominated a slate of “state” officials and sent the whole question to the voters. But they made one major slip. Supporters of statehood were thoroughly convinced they would win, but greedy Denver grabbed almost all of the important nominations. At that point, the scheme started to unravel. Mountain towns, led by Central City, bolted and to the horror of Byers and the others, statehood lost.

Not one to give up, Chaffee renewed the fight in 1865, finding a worthy opponent in Central City’s Henry Teller. An ambitious man, Jerome Chaffee had his eye on the United States Senate. For the next decade, the two men led rival factions of the Republican party and the press flowed with charges and accusations.

Chaffee organized his wing brilliantly, and captured control of the party, then initiated another “state” election. This time it passed, but the voters rejected “Negro suffrage.”

So back to Washington they went. But the suffrage issue was hot in Congress, with the Republican radicals pushing hard for it nationally. And Colorado got turned down for statehood several times, not only because of its stand on suffrage, but also because Teller and his supporters carried their case against statehood to Washington — where they skillfully used arguments that the territory did not have a large enough population, and questioned the legality of the election on statehood. They also charged that the enabling legislation was no longer valid.

THE RESULT WOULD MEAN no statehood until 1876. But Chaffee, in the meantime, was elected territorial delegate, a non-voting position, and he kept control of the party.

Finally, a series of events, including some bad territorial appointments, corruption, and the desire to control their own destiny led to a final push for statehood.

President Ulysses Grant made the appointments, and there is a legendary story about poker, a long evening, and probably a few drinks, during which Chaffee convinced Grant to appoint a new governor and set the stage for statehood. Later, Jerome Chaffee’s daughter married Grant’s son.

By 1875, Chaffee and Teller reconciled their differences and led a unified Republican party, and the desired result finally came about. Statehood was proclaimed on August 1, 1876. The state legislature then named Chaffee and Teller senators, there being no direct election of senators for another generation. Chaffee lost the draw for the six-year term, served for two years and because of ill-health, retired. Regaining his spirit, Jerome tried to make a comeback and failed but he continued on as “Boss Chaffee” almost until his death — even though he eventually moved back to New York.

ALWAYS IN PURSUIT of money, as well as political power and office, Chaffee continued wheeling and dealing in Colorado mining property. He and Smith dabbled in Georgetown silver mines in the 1860s, as that town became Colorado’s first silver “queen.” They organized a group of Central City investors into the Georgetown Silver Smelting Company, purchased a mine, and built a smelter. It was the best in the county at the time (1867); and displayed a thirteen pound silver “button.” But they promptly sold the mill.

Chaffee and his partners promoted and sold mines; he received fees as a broker, and also helped sell stock at an inflated price. Jerome and others had learned that investors would invest in a property and spend tens of thousands of dollars before actually knowing if the mine or mill had proven itself. Selling properties was an easier road to wealth than actually testing and working the mine or mill.

Their multitude of promotional means were wondrous but”often fraudulent.” The two classic cases of Chaffee’s wheeling and dealing occurred at Caribou, over in Boulder County, and in booming Leadville. The deals happened almost simultaneously with a common pattern: Jerome ending up with the money and the others with the mines or stock.

Discoveries at Caribou in 1869-70 heralded Colorado’s silver decade. The Caribou, the most famous mine in the district, had been sold to Dutch investors in 1873 for the then unheard of amount in Colorado of $3,000,000. Undercapitalized, with a mine that had been gutted before the final sale, the Mining Company Nederland went bankrupt within three years.

In July 1876, Chaffee purchased the property at a sheriff’s sale for $70,000. Soon charges flew that he had been involved in everything, from the original sale, to demoralizing the Dutch stockholders, to deliberate “mine butchery.” And Chaffee had, indeed, brought suit on behalf of himself and the First National Bank relating to loans.

Joined by Moffat and others, the new owners put Smith in charge of the mine. While Chaffee cleared claims against the property, Smith skillfully brought it back into production. The Caribou soon regained its former status as one of Colorado’s great silver mines.

The end result of this could be easily predicted. Moffat and Chaffee sold the mine, and its Nederland mill for $1,000,000 — a tidy profit in 1879. All this happened just in time to rush to Leadville.

That was not the end of the Caribou Mine story, however. Within two years, amid lawsuits, high expenses, and low grade ore, the mine shut down. The role of Chaffee and Moffat remained shadowed in mystery. Had they brought it back into production for one reason, and only one, to sell it? They definitely left with a profit and sold what stock they had in the new company before the collapse.

HAD THEY SUSPECTED that the mine was almost “dug out”? No one can say, and no records remain. Chaffee would find himself in court over these Caribou transactions until the year before his death.

His involvement in Leadville’s famous Little Pittsburg Mine parallels the Caribou story. The Little Pittsburg, which laid the basis for Horace Tabor’s fortune and started the Leadville excitement, had attracted Chaffee’s and Moffat’s attention early on. They joined with Tabor, incorporated the mine, sold stock, and promoted the endeavor. Everything went smoothly, with the stock jumping into the $30 range, but then it suddenly collapsed in February 1880, slipping to $7.50 a share.

Accusations flew thick and fast — especially regarding company president Chaffee and vice president Moffat. Leadvillites blamed New York capitalists; easterners blamed Western betrayal. Chaffee was accused of selling out secretly when he knew the profitable ore was almost exhausted.

It was discovered that Chaffee, in March, telegraphed Moffat to sell out, while he told the press that he was the “heaviest loser” in the crash and had not been involved in inside trading. But as it turned out, he and Moffat had sold 51,000 shares in February.

Moffat blamed the mine, not the management, for the collapse and denied any wrongdoing, claiming he really knew nothing about mining. This, he lamely asserted, was his first stock operation. Chaffee said the vein had pinched out, but he had hoped that new deposits would be found. Their explanations weren’t very convincing, however.

RUMORS WERE BANDIED ABOUT, and denials countered accusations, but still the whole story failed to emerge. Nor has it since. Chaffee, Moffat, and all of the others involved withdrew with their profits. By year’s end, the dismal descent continued, falling under $2 per share, and stockholders were left holding the bag.

Although there are differences, the story of the Caribou and Little Pittsburg mines create an obvious pattern, particularly when some of Chaffee’s other activities are thrown into the mix. Mining in the nineteenth century always created investment risks, a fact Chaffee completely understood. It was sharp business to get in and get out, but in the Little Pittsburg case, Chaffee definitely used inside knowledge to get out in time.

Chaffee and his partner Moffat cannot be convicted of more than using inside information. The direct evidence is not there to convict them of crooked or at least shady manipulations. But these episodes would dog Chaffee for the rest of his life, particularly in Colorado’s Democratic press.

Despite the “dark side” of Jerome Chaffee’s wheelings and dealings, however, Colorado gained promotion, statehood, development, and a political coming of age with his help. In his day, Chaffee gained fame, praise, and power along with suspicion and condemnation, but he gleaned very little lasting recognition.

Now, however, in our own era of big money manipulations and insider trading, it seems fitting to spare a moment to reflect on the career of Jerome Bonaparte Chaffee, the namesake of Chaffee County, and a past master of questionable finance.

Duane Smith is a professor of history at Fort Lewis College in Durango and the author of many books about Colorado’s history. His recent books include: San Juan Gold: A Mining Engineer’s Adventures, 1879-1881(Western Reflections, 2002) and Mesa Verde National Park: Shadows of the Centuries (Revised Edition, University Press of Colorado, 2002).