By Ron Sering

Not much goes on these days in sparsely populated Wellsville, a few miles east of Salida, off U.S. Hwy 50. Home now to a couple of modest mining and milling operations and several private residences, the booms that had periodically rippled through the state have passed it by for many years. But that was not always the case.

There is some evidence that Native Americans once spent winters in the area, but Wellsville, the town, was founded in the late 1800s by namesake George Wells. Drawn by the area’s mineral wealth, miners worked the dry hills and canyons for gold, silver, copper, and quick lime, but most prominently for travertine, a sedimentary rock commonly formed from the action of hot springs. Prized as a building material since Roman times, travertine from Wellsville quarries was used in numerous public building projects, including the state Capitol in Denver and the Department of Commerce building in Washington D.C.

The mid to late 1800s was a prosperous time in the Pleasant Valley and throughout the region. Minerals and lumber flowed from the mines to the flatlands. Kilns throughout the region converted pinyon to charcoal to feed the Colorado Fuel and Iron Steel Mill in Pueblo. Wellsville grew to include a one-room school, general store, and post office. When the Denver and Rio Grande railroad extended service to Salida in 1880, the line ran through Wellsville, as did US Highway 50, which then ran along the river’s east bank.

Mining peaked in the area before the turn of the century; work in the travertine quarry continued into the 1920s and in aa reduced capacity throughout most of the Great Depression. But a Salida mining and lumber entrepreneur, Vorhis C. Davenport, had already prepared Wellsville for another boom, one based on Wellsville’s other geological asset, the warm springs.

“There it is, that’s the source,” said Steve Finch, whose family first homesteaded the area in the mid-1800s and have owned the spring and surrounding property for nearly a century. He pointed to a marshy area at the base of an enormous black boulder. Fingertips in the water revealed a distinct current flowing from it. Steve credits his great-great-grandfather, Daniel Heister with discovering the spring. “When he found it, it was just a bear wallow.”

Located on the edge of the Rio Grande rift, geothermal activity bubbles beneath Wellsville’s surface. “A 1979 study found that the water temperature ranged from 28 to 33 degrees Celsius,” said Fred Henderson III, chief scientist of Mt. Princeton Geothermal. Translating in Fahrenheit to 80-90 degrees, “this classifies Wellsville as a warm spring.” The report estimates the flow at 160 to 200 gallons per minute, with a high mineral content.

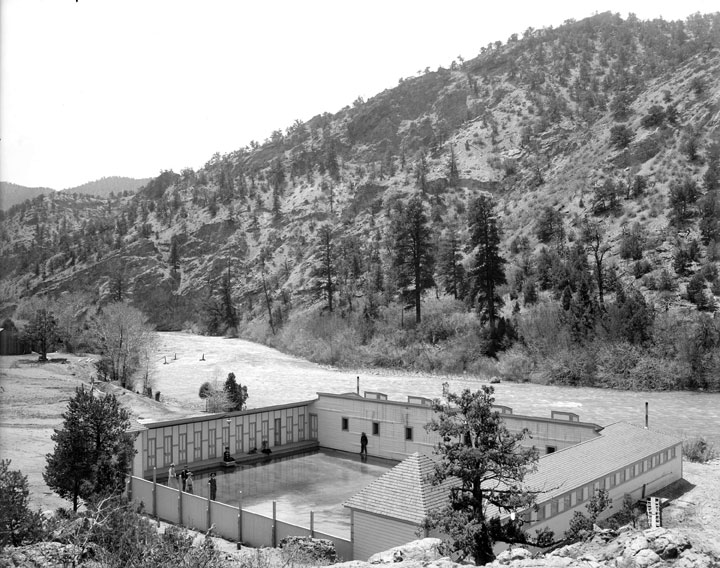

Davenport purchased the warm springs in 1900, and by 1904 the resort was in full operation, with a two-story hotel, indoor and outdoor pools, a large hardwood dance hall, and picnic areas. In its listing for Davenport, Progressive Men of Western Colorado, a who’s who of men in the early West, described the project as “a popular summer resort which grows in favor every year.” With easy access by road and rail, and with the water’s reputed curative powers, it became a haven for stressed-out flatlanders seeking respite from the Roaring Twenties.

“They came on the train, spent the day, and then when it came back at the end of the day, rode it back home,” said Steve’s father, Ed.

The hot springs was later purchased by Charles (Brownie) Wickers, Finch’s great-grandfather, and operated throughout the 1920s; the resort hosted holiday crowds estimated at 1,000 visitors. Baseball was popular in the area, with teams coming from all over the Upper Arkansas river valley to compete. The resort brought people on the trains from as far away as Denver. “I remember my great uncle, Clark Wickers telling me about people just running from the trains, buckets in hand, to get to the waters,” said Steve, who lives there still. “It didn’t matter who they were, black or white, they all came and shared the water together.”

Amidst the festivities, there was the occasional scandal or tragedy. In the summer of 1932, a Salida businessman discovered his wife and a local man having a rendezvous at the popular resort. He gunned down the lover in the hotel lobby, and killed his wife at the pools before turning his gun on himself. Reports from the time said that the bodies of the lovelorn husband and his unfaithful wife were found floating in the pool.

The Great Depression brought a reduced number of visitors. Eventually, the dance hall closed, though later in the 1930s it reopened as a skating rink. The resort experienced a number of natural disasters, including the 1945 Waldo Gulch flood.

Former Wellsville resident Bill Williams wrote, “the river was completely dammed up by this flood and was backed up a half mile toward Salida. The water was so full of dirt and floating debris that it filled the Wellsville pools with the fine silt and washed out the buildings that were dressing rooms and covered the two inside pools.”

While the resort is no longer open to the public, the property is home and sanctuary for various family members, each of whom owns a portion of the property. Little remains of the resort. Steve Finch pointed to a cabin, worn with age which still stands. “My grandfather came back from France in WWII, and lived right there.”

Elsewhere, a concrete pillar the size of a small SUV, is all that remains of the dance hall. The lower part of the old hotel still stands. Two pools, though closed to the public, still operate, one teeming with tropical fish. “My grandfather introduced these fish,” Steve said. “He passed away in 1987, but the fish just live on.” The other, also more along the lines of a warm bath, is reserved for family bathing.

The Finches are barely fazed by the many booms and busts that the state has encountered, and seem to like it that way, despite the occasional generous purchase offers, “This is our history here,” Steve said. “Five generation’s worth. We’re not monetary driven-people. It’s just not for sale.”

Ron Sering lives and works in Howard, where it’s also pretty nice.