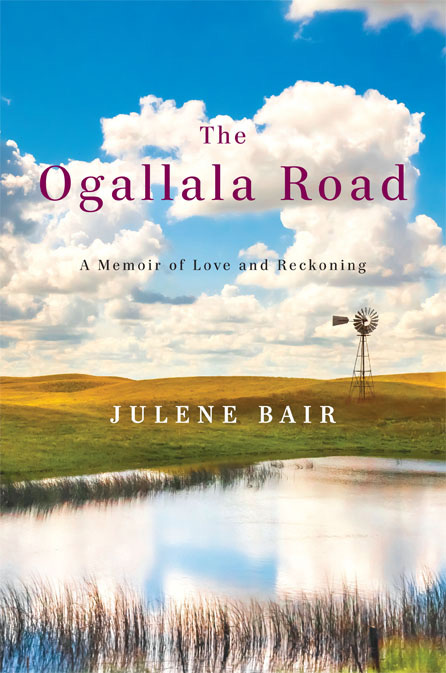

The Ogallala Road– A Memoir of Love and Reckoning

By Julene Bair

Viking, hardback, 278 pp, $26.95, ISBN-13: 978-0670786046

Reviewed by Annie Dawid

On a boulder-strewn hill behind the cabin, pink barrel cactuses fended off would-be moochers with whorls of bright-pink spines, and in the gorge between that hill and the cabin, water trickled. The pools were too tiny to immerse myself in, but a mile upstream stood a windmill beside a six-foot-tall stock-water storage tank where I could go swimming! Well, dunking anyway.

The above is a sample moment Julene Bair describes in her love story/ecology tutorial/memorial to her Kansas family farm, The Ogallala Road. As a young woman she spends months alone in the Mojave Desert, appreciating every particle of color, light, and, especially, water. With humor, grace, and hard-won wisdom, Bair tells her story of life on the Western Kansas high plains as the child of a farming family, and her subsequent travelogue through many landscapes of adulthood, landing her, finally, here in Colorado.

But the book’s focus is the part of Kansas near the Colorado border in which her family history is grounded, as is her relation to water, its presence and rapid disappearance from the landscape. The Ogallala Aquifer, the largest in North America, supported the irrigation of Bair’s family farm and thousands like hers, followed by agribusiness, which ate up the smaller farms, including hers. Decades of irrigating chemical-intensive crops like corn have wrought irreparable damage to the ecosystem. By the end of the memoir, the reader will have learned the rattling history of 20th and 21st century agricultural depredations on the land, and especially, how it has ravaged our water supply.

But the book’s focus is the part of Kansas near the Colorado border in which her family history is grounded, as is her relation to water, its presence and rapid disappearance from the landscape. The Ogallala Aquifer, the largest in North America, supported the irrigation of Bair’s family farm and thousands like hers, followed by agribusiness, which ate up the smaller farms, including hers. Decades of irrigating chemical-intensive crops like corn have wrought irreparable damage to the ecosystem. By the end of the memoir, the reader will have learned the rattling history of 20th and 21st century agricultural depredations on the land, and especially, how it has ravaged our water supply.

Life needs water. The only water we had came from the aquifer. If we were mindful of this, we could call ourselves the Ogallala People, not after the tribe that lost its home to our invasion but in recognition of our life source. The name would cascade as water does, down stairs of years – the tribe, the town, the aquifer – onto us.

What we learn about mainstream American farming, its profitability and dependence on toxic chemicals, is enough to make even the least squeamish reader want to give up corn forever. Bair is brutally honest with herself and her reader as she comes to understand the damage her family farm has caused to the earth she loves with such passion, yet the Bair family’s contribution to this massive onslaught is minor. The entire practice of crop-irrigation on the high plains is the culprit – the assumption that the billions of gallons of water pumped from the aquifer will continue forever, world without end.

But, Bair warns us, it will end. It is already ending. And the budding love affair with the Kansas cowboy, which begins the story, will end too, the reader senses, as too-good-to-be-true. Nevertheless, it’s a great ride; the twice-divorced Bair meeting a marvelous man while searching in the Kansas boonies for springs, and their subsequent passionate encounters. He’s even read her first book! Bair describes her physical intimacy in a refreshing way that doesn’t make the reader feel like a creepy voyeur. In her acknowledgments, she thanks another writer, Susan Gordon Lydon, “who, although she was terminally ill, kept me laughing while convincing me it was okay to write honestly about sex.”

In addition to the cowboy boyfriend, Bair’s father, son, brothers, mother and friends play crucial roles in this coming-of-a-certain-age memoir. Solitude and loneliness dance with one another, alternating with the undeniable sense of rootedness her Kansas homestead offers her, though she must reject it and return, reject it and return, drawn to what she loves as well as despises. As she studies the damage irrigation has done, she comes to understand that the entire way of life of High Plains farmers like her father and brother is itself toxic to the land: profit always trumps conservation.

Our sense of beauty is a survival instinct, telling us that a place can sustain us for generations to come. I’d always known this in my bones, but it wasn’t until many years after I left Kansas and discovered my passion for wilderness that the intuition became conscious.

Bair is adept at making conscious what lies beneath the surface: water sources beneath the dirt soil as well as intentions underlying human behavior. Haunting her story is that of the Cheyennes, what she calls the “pre-us” period of High Plains history.

The low-growing grass stitched itself over the ground like a wooly tapestry, accented, especially in the spring, by other pastels. Blue grama grass. Apricot mallow. The yellow and cream waxen blooms of cactus and Yucca. Prairie dogs chirped alarms from mounds of whitish clay, and meadowlarks sang from their perches on yucca spires, their notes climbing and dipping like winding ribbons. Instead of cows, I imagined buffalo grazing the hills. The grass had been named after the buffalo because millions of them once thrived on it.

A specific brand of nostalgia pervades her beautiful writing, the longing for places we have never been, that unspoiled, untrammeled world formerly husbanded by the aboriginal peoples, now vanished.

On the flat part of the farm, I had been painfully aware that the land was being enslaved and abused. Standing there (in the hilly area) proved to me that it could all be put back someday …. Ever since I was a child, I’d been thrilled to imagine the world ‘pre-us.’ I wasn’t exactly thrilled to imagine it ‘post-us,’ but I did take some comfort knowing that it might recover from our brief and injurious tenure.

“Miss?”

By Laurel McHargue

Publishing Syndicate: 2013

ISBN: 978-1-49364-770-5

$12.95, 228pp.

Reviewed by Eduardo Rey Brummel

Laurel McHargue’s name is not uncommon to Colorado Central readers, and some of her essays are archived on the magazine’s website. If you have read her work, you already know she shows a sturdy handling of the stories her essays tell, and often with a sublimely screeching sense of humor. Further, she’s been a strong supporter of the magazine and its writers, behind the scenes.

Publishing Syndicate has recently released McHargue’s novel, “Miss?” which tells the story of Maggie McCauley, who’s returned from active duty in the Middle East war zone and is now beginning her teaching career in a struggling Denver inner-city middle school. After her time in the military and overseas, Maggie thinks dealing with seventh graders will be a comparative cakewalk. Well, not so much, it turns out – as any parent or teacher of adolescents already knows too thoroughly.

I enjoyed this book. I never had to “push through” to read it, never felt it was a poor expenditure of my time doing so. However, I do see problems. Specifically, I believe that some of her characters, and some of the events that take place are unnecessary. Also, her characters seem at times a wee bit too black and white in their behaviors and moods. It would have been nice to have Maggie’s next-door neighbor call her to task for her whining, and for the security guard to have done something commendable before his fall from grace.

In his interview in the September 2010 issue of Writer’s Chronicle, Andre Dubus III said, “Oh, I’ve thrown away more novels than I’ve kept, and really, the four books I’ve written are phoenixes that have risen from the ashes of my failures.” McHargue’s essays show such a higher caliber of capability that I question whether this should have been her first published novel.

But let me get back to McHargue’s successes, for as I said, I did enjoy reading this book. She does otherwise have a good handle on her characterizations. I’ve crossed paths with pretty much each of the people who inhabit her story. Some of them, I’ve met several times, or even too many times. They were real and vivid to me, especially the students. I have a teaching degree and license. I’ve let them sit unused on the shelf due to many of the same struggles Maggie goes through, which is another aspect of the storytelling McHargue gets right.

Finally, also, and again, McHargue’s novel is enjoyable to read. Isn’t that the true measure of a story’s worth? I dreaded approaching the final chapters. I knew I wouldn’t be ready to leave already, and so soon.

Eduardo Rey Brummel is grateful for his own seventh grade English teacher, Regina Cole, who championed his writing – even after he’d told her, “English is my least favorite subject.”