A Local Hydroelectric Plant Passes the Century Mark

By Ron Sering

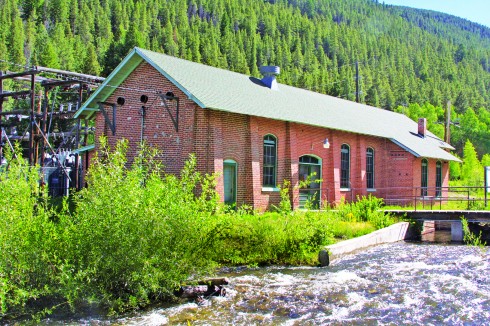

There are many remarkable things about Salida Hydroelectric station two. The location itself is dense with history. The distinctive red brick powerhouse is situated a short distance from the train track that once linked Salida with its historic mining operations. The Victorian structure and the generator it houses have an elegance that modern designs can’t match.

The facility’s other distinguishing feature is its longevity. Apart from changes in instrumentation and upgrades to the turbines, the generator looks and functions much as it did when it was first installed in 1906. Pipes feed water past two turbines, which turn the generator at a relatively sedate 200 rpm. Currently owned and operated by Xcel Energy, the generator churns out a maximum of 400 kilowatts of emission-free power, as it has for the better part of a century.

“We don’t really know what the life of a hydro generator is,” says Alfred Hughes, manager of hydroelectric operations in southern Colorado. “You’re going to be replacing components, rewinding generators. You have to maintain them correctly, but they can pretty much run forever.”

The Salida Hydro operation uses a method called “run of the river,” which relies on a gravity-fed water supply to operate the generators. The method requires a relatively small amount of stored water, but power output can vary depending on the runoff. “Mid-May to mid-June is our peak,” said Hughes. He noted that peak runoff now occurs earlier than in the past. “The peak used to be around Father’s Day in June. We’re clearly peaking three weeks earlier on all these hydros than we used to.”

Hughes has been involved in hydroelectric operations in the state for over thirty years, and shuttles between other facilities, including the Ames station near Ophir. “Ames was the first practical application of alternating current in the world,” Hughes said.

With its vast wealth of rivers, Colorado is the home of some of the earliest applications of hydroelectricity. The Ames station was the first application of alternating current in 1891, predating Niagara Falls by almost a half decade.

Today, alternating current is the dominant form of electricity, but in the late 19th century it was a toss-up between the alternating current of Nikola Tesla and George Westinghouse, and Edison’s direct current. AC, capable of more efficient transmission over distances, eventually won out. “Without alternating current and the ability to transmit electricity, we wouldn’t be where we are today,” Hughes said. The project was part of the Colorado Power Company with Shoshone Hydro, which in 1924 became part of Public Service Company of Colorado, a predecessor of Xcel Energy.

Like Ames, the Salida Hydro stations initially provided power to the mining operations that put Salida on the map. The operation begins near Garfield, where water is diverted to Fooses Reservoir at 8,900 feet, which serves as the supplier, or fore bay, of water for Salida Hydro one.

Water is gravity-fed by a supply line known as a “penstock” to the station. Salida Hydro station #2 lies several hundred feet below Fooses. Here, the old generator was replaced in 1925 by a higher capacity unit. The unit is currently offline, pending repairs to its service line. When it is operational, the generator produces the bulk of the maximum 1.4 megawatts produced by Salida Hydros one and two. “Enough, in this day and age,” Hughes said, “to supply about 1,200 homes.” Hughes expects station one to be back online later in the summer. Another penstock delivers water to Salida Hydro two. Here, a smaller reservoir holds the water. Outside the station there are no emissions, and only minimal noise.

The facilities are not without detractors. Trout Unlimited, a national conservation group, released a 2002 report, “A Dry Legacy: The Challenge for Colorado Rivers,” citing reduced flow due to agricultural and hydroelectric diversions, with possible adverse effects on fish populations in the Little Arkansas.

Two bypass flows were installed as part of the plant’s 1997 license renewal, one at the Garfield diversion and another at Salida Hydro two. The combined bypass flow returns a peak flow of five cubic feet per second to the river. A habitat restoration project jointly funded by Trout Unlimited and Xcel Energy was completed in 2009. Collegiate Peaks Anglers, the local TU chapter, was awarded a 2011 Embrace-A-Stream grant to conduct assessments of the Upper Arkansas and to plan further habitat restoration. Licenses are renewed for thirty year periods. The license for Salida Hydro is up for renewal in 2027.

Both reservoirs, regularly stocked by Colorado Department of Wildlife, are popular fishing locations. “The local fishermen know the stocking schedules, and come out in large numbers,” Hughes said. The facilities themselves attract school groups and history buffs. Xcel hosts tours, which can be scheduled by phoning 1-800-895-4999.

Despite giving up the mean streets for dirt roads, Ron Sering washes his truck even less than he used to. His fiction and nonfiction work has appeared in original anthologies and publications that include Inside Ecuador, The Nashville Tennessean, and Cemetery Dance. His website is www.ronsering.com.