by Mary Syrett

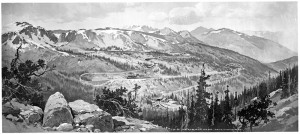

In April of 2011, while hiking among the sand dunes in Great Sand Dunes National Park, I heard something unusual. If you listen carefully, you may discover that sand at various locations among the dunes “sings,” making audible sound vibrations.

Sand dunes in the park do seem to have a built-in “sound track” – a phenomenon that has been reported from other widely separated dune areas. While “music” emanating from the dunes at times can be compared to the strains of a chorus in the distance, the effect at other times more closely resembles the playing of violins.

Reverberations and vibrations oscillated into world headlines in 1969 when Apollo 12’s astronauts sent Intrepid’s descent stage, crashing into the sandy Ocean of Storms on the moon. Scientists are still trying to understand the bell-like reverberations that were recorded through a moon-based seismometer. They lasted for 55 minutes after impact.

A sand dune, whether on the moon or in Colorado, would not seem to be a likely candidate as a natural sound generator. The fact is, however, dunes in many parts of the world squeak, roar or boom. Many writers have discussed this curious phenomenon.

Indeed, for a thousand years and more, literature has mentioned singing sands. Venetian traveler to the Mongol court of Kublai Khan, Marco Polo, frequently referred in The Travels of Marco Polo to musical sands and the superstitions attached to them.

The ancient Chinese knew of the phenomenon as well. One Chinese writer left an account of an area in Kansu Province where noise-generating sand was noted in the 9th century. The document speaks of a “Hill of Sounding Sand” that was 500 feet high. According to the author, it possessed strange supernatural qualities: “The peaks taper up to a point, and between them there is a mysterious hole which the sand has not been able to cover up.”

The writer observed that in the summer, when men or horses trod upon the hill, sounds could be heard for great distances. The manuscript spoke of a custom that was used to induce singing sands: “It is customary during the Dragon Festival for men and women from the city to clamber up to the highest points and rush down again in a body, which causes sand to give forth a rumbling noise. Yet when you look at it the next morning, the hill is found to be just as steep as before. The ancients called this the ‘Hill of Sounding Sand’; they deified the sand and worshipped it.”

In the Western Hemisphere, essayist Henry David Thoreau came upon singing sands while walking on a New Hampshire Atlantic Ocean beach. He noted the sound resembled that made by rubbing a finger over wet glass.

British naturalist Charles Darwin was the first scientist to discuss the phenomenon. In his book A Naturalist’s Voyage Round the World, an entry for April 19, 1832 reads: “Leaving Socego (Brazil), we retraced our steps. It was very wearisome work, as the road ran across a hot, sandy plain, near the coast. I observed that each time the horse put its foot on the fine siliceous sand, a chirping noise was produced.”

Some 300 years ago, a strange Middle Eastern legend arose, a legend Darwin had heard about. It concerned a monastery buried in sand for centuries, the bells of which still were heard to give off a drawn-out ringing note. People passing by were awestruck as they came within earshot of the mysterious ringing dune. European pilgrims also heard a prolonged sonorous sound. But the place where they heard it was deserted, with no priests or other human beings in sight. In time the “Mountain of the Bell” passed into legend.

Intensely curious, Darwin decided to investigate. Visiting the locale, he sat down on a rock and asked a guide to climb up the sand mountain on the “musical” side. “It was not until the guide had reached some distance,” Darwin wrote, “that I perceived the sand to be in motion, rolling down the hill. In the beginning, the sound might be compared to that of a harp when its strings first catch the breeze. As the increased velocity of the descent agitated the sand, the noise more nearly resembled that produced by drawing a moistened finger over glass. As it reached the base, the reverberations sounded like distant thunder.”

Musical sounds, such as those Darwin heard, occur in localities widely distributed over the earth’s surface. Best known, perhaps, is on the island of Eigg, off Scotland’s western coast. Anthropologist Hugh Miller, in his book The Cruise of the Betsy, published in 1858, first described sounds heard there. Miller noted that when he kicked the Eigg sands at an oblique angle, they gave off “a shrill note, resembling that produced by a waxed thread when tightened between teeth and a hand, then tripped by a forefinger.”

Other places where “singing sands” have been heard include Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge on the South Carolina coast, the Outer Banks of North Carolina, Rockaway Beach on Long Island, the western coast of Wales, the island of Bornholm off the coast of Denmark, and New South Wales, Australia.

What produces the sounds? Singing sands may involve thin films of air or gases, deposited and condensed upon the surface of grains during evaporation. Such films may act as elastic cushions separating the quartz grains. These cushions are capable of considerable vibration, which may be translated into sound, produced after any quick disturbance of sand.

Another possible explanation is that certain sandy stretches of beach are bathed in waters which contain various salts, including calcium and magnesium bicarbonates. When water dries, the salts coat the grains and, when friction is applied through rubbing, may produce a sound somewhat comparable to the action of rosin on the bow of a violin.

The “singing” of sand may be the audible consequence of billions of minute crystals being tumbled and rolled one against another by wind. Or, since “singing” is sometimes more pronounced after sundown, another theory could hold true. A mass of sand absorbs heat during the day and, with nightfall, as each sand particle cools and contracts, a dune shifts and settles; in such movement, sounds may originate.

Spontaneous “music” arising from beach and desert sands around the world has long captivated the imagination of writers and scientists. The next time you’re hiking among sand dunes in Great Sand Dunes National Park, keep an ear open for one of the strangest concerts ever to come from nature. If you listen carefully, you may hear a hauntingly beautiful sound, especially in the quiet of a summer or fall evening. Singing sands are a natural curiosity, a phenomenon in Mother Nature’s bag of tricks that astonishes all who hear them.

Mary Syrett is a Colorado Springs native who for now lives in the Research Triangle Park Area of North Carolina, where her spouse is a visiting professor. She misses home.