Moose foothold gaining strength in Central Colorado

By Christopher Kolomitz

Once considered a rarity in the state, moose are quickly becoming another attraction to the Colorado wild lands, right up there with snow-covered peaks, blazing aspen stands and cold, clear streams.

Specifically, it’s the Shiras moose that has tourists and locals doing a double-take. Typically smaller than their cousins to the north in Canada and Alaska, the Shiras moose has gained a foothold in Colorado, thanks to reintroduction efforts by state wildlife officials, a lack of natural predators and abundant suitable range.

When out on a drive, hike, mountain bike ride or cross country ski, spotting one of the long-legged creatures is happening more often, especially in Central Colorado’s lush backcountry wetlands and other riparian zones.

“It’s not a common experience to see a moose. But at the same time when someone tells me that they saw one up by St. Elmo, it’s not alarming at all,” Jim Aragon, the Salida Area Wildlife Manager Colorado Parks and Wildlife said.

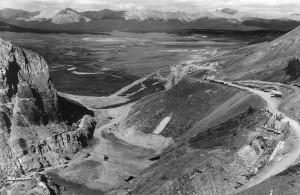

According to state wildlife officers, moose sightings are known to occur in 38 Colorado counties – basically in areas west of Interstate 25. Wildlife officials list those sightings in some counties as more rare than others, but nonetheless, it can happen. In Central Colorado, several counties stand out as having prime moose habitat and range, with major concentrations occurring in a places along or west of the Continental Divide.

Aragon travels all over the Upper Arkansas River Valley and has spotted moose in lots of places – Weston Pass, north of Buena Vista, drainages around O’Haver Lake and around the Buffalo Peaks area.

While most commonly spotted at higher elevations and near wetlands, moose have been seen around Chaffee County in lower lands and on the “dry” side or eastern side of the Upper Arkansas River Valley.

A motorist spotted one by the Arkansas River and Ruby Mountain. Wildlife watchers reported seeing a cow and two calves in the Ute Trail area north of Salida. A few weeks later, Aragon said the same three moose were spotted near Howard. A few summers ago, a bull moose was hanging out in a pasture off U.S. 50 west of Salida. The landowners spray-painted a sign with an arrow telling passersby where to look.

Wildlife officials list nearly all of Lake County as suitable moose range. In Park County, the best range is west of U.S. 285. Likewise, in Chaffee County, the best moose range is found west of U.S. 285 and the areas north of Buena Vista. Last winter, a backcountry skier spotted a moose in the Mineral Basin area near Cottonwood Pass. Other trophy-size moose are rumored to inhabit both sides of the pass.

Perhaps the best moose range in Central Colorado is in Gunnison County, where the territory north of U.S. 50 is considered suitable. The areas east and a bit north of Taylor Reservoir are known to have higher concentrations of the animal. Other prime areas include the northeastern tip of the county around McClure Pass and into Mesa County. During the 2011 elk archery season, a hunter in Gunnison County filmed a massive moose and posted the video on YouTube. The area isn’t open for hunting.

In the San Luis Valley, the western third of Rio Grande County and nearly all of Mineral and Hinsdale counties have good moose habitat. The area east of Lake City in the La Garita Wilderness within Hinsdale County hosts a sizable concentration too.

Residents of Lake City report that the area around Deer Lakes is sure a spot to see the creatures. Just the western third of Saguache County is suitable, although a concentration exists near the La Garita Wilderness and in the Groundhog Park area north of U.S. 160.

Outside of Central Colorado, notable populations inhabit Summit County, especially around Dillon. Moose concentrations are also found further north into Grand County around the Williams Fork Mountains and then into the Winter Park, Frasier and Granby and Grand Lake areas.

Large populations are found also in the northern part of the state, in Routt and Jackson counties that make up the area known as North Park and in the northwestern parts of Larimer County near the Wyoming border. In the mid-1990s the state legislature called the area around Walden the “Moose Viewing Capital of Colorado.” Earlier this winter Steamboat Springs residents watched as moose licked salt from vehicles parked in a residential neighborhood.

And, moose, which are known to wander huge distances, are being found more often along the Front Range, with moose sightings occurring in Golden and elsewhere.

The moose that people are seeing now have traveled into favorable lands after their descendents were transplanted into the state. Historically the Shiras moose may have migrated into the northern parts of the state from Wyoming, but likely there never was a viable population, wildlife officials said.

Photographs and records do show some moose in the state, with a Denver parade around 1900 featuring a moose along with other wild animals. Early forest managers on the Western Slope made notes of very small populations in the late 1800s. Some historians believe moose were probably hunted to near extinction in the state by early Native Americans and early settlers because of their massive quantities of meat and their lack of human fear, which made them easy targets. Other limiting factor for a native moose population is the state’s relatively warm climate.

In the mid 1970s state wildlife officials began transplant efforts, first looking at the willow-bottom areas on the West Slope of Gunnison County. However, because of local rancher opposition, areas around North Park became more favorable and that area became site of the first moose transplant in 1978.

Locally, wildlife managers and U.S. Forest Service officials determined there is suitable moose habitat in the Upper Rio Grande drainages and between 1991 and 1993 they transplanted 92 moose. They had come from Utah, Wyoming and North Park and with the help of dedicated volunteers they were released at 12 locations near Creede.

Those 92 moose blossomed in the Upper Rio Grande and traveled as far as 150 miles and by the summer of 2000, the population in the area reached almost 400. Since 2005, moose transplant efforts have also been happening on the Grand Mesa, east of Grand Junction. Current population estimates by the state wildlife department sit at about 1,700.

Moose in Colorado have very few natural predators. A mountain lion may prey on a calf, injured or sick moose, as would a black bear. But the state is missing predators like wolves and grizzly bears, which has allowed the moose population to grow and mature. Typically, a moose lifespan is about 8-10 years but some may live up to 20 years in perfect conditions. They can be impacted by chronic wasting disease, although very few if any cases have turned up.

Perhaps their biggest threat comes from humans driving cars or humans with guns. In fall 2011, state wildlife officials sent out a reminder for motorists to watch for moose along Colorado highways. The reminder came after a woman died when the vehicle in which she was a passenger hit a cow moose along I-70 in Summit County. Officials said they lose five to eight moose a year on major highways in that county.

Wildlife officials are also making a major push to educate hunters regarding proper target identification. In the fall of 2011, wildlife officials investigated more than a dozen inadvertent moose kills. Most likely those incidents involved some combination of low-light conditions, an incomplete or long-distance view of the animal and poor judgment by the hunter, leading to misidentification of the target. In 2010, officers investigated 14 incidents where hunters wrongly killed moose. “Elk don’t stand around and watch you,” a wildlife official said. “If it sees you or smells you and doesn’t run away, it’s probably not an elk.”

Moose are solitary creatures, they don’t join in big herds like elk or deer, although males do spar during the rut in late September and early October. They prefer alpine areas, beaver ponds, marshes or willow bottoms and you most likely won’t find them in rocky or cliff areas. Calves, typically born in late May and early June, stick close to mom and are often twins.

Their diet changes seasonally, with the summer bounty consisting of willows, grasses, forbs and underwater vegetation. Summer sun and rain showers help grow tender shoots of conifer and deciduous trees, which are favorites of moose too. It’s estimated they eat more than 25 pounds of vegetation daily in the summer.

In the winter months they browse, using their long legs to trudge through snow and ice to find willow snacks. Often, during the winter, moose will stay in one area of suitable food sources and create paths among the snow to reach their food. Winter consumption is around 11 pounds daily.

Because of their natural instincts to protect themselves against wolves, people walking dogs and should be aware of aggressive tendencies of moose when threatened, wildlife officials said. Officials also suggested giving moose with calves plenty of room and not getting too close to bull moose during the rut. Indicators of agitated moose include ears pinned down. Basically, use common sense when watching moose, wildlife officials said.

Christopher Kolomitz is a former Salida journalist who recently returned to the Upper Arkansas Valley after spending too much time in traffic. He has a moose story from Wyoming and is anxious to see one soon in Central Colorado.