By Forrest Whitman

Readers of Colorado Central have probably driven right next to the roadbed of a spectacular railroad loop without noticing it. Even today, the Rio Grande’s Texas Creek extension gives us spectacular views of a line built around the mountainside and up to the sky. Getting a view and photo of its high reaches above the Arkansas Valley led us on a trip there recently.

The line from Texas Creek station to Westcliffe was part of an ambitious extension of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad completed in 1900. We found most of the original line not only traceable, but easily photographed, as the accompanying photo shows. For this writer, the line also evoked some special memories of days working on the railroad with some relevance to this line.

Parking is easy at Texas Creek Junction, right across the river from U.S. Highway 50. We trained our gaze upward even as we parked. The BLM has a maintained and easy to find parking area there.

It’s fun to imagine the main line coming up from Cañon City and the branch line heading on its 25-mile journey up to Westcliffe. That canyon must have echoed with the steam whistle as trains left to climb up to Inspiration Point far above.

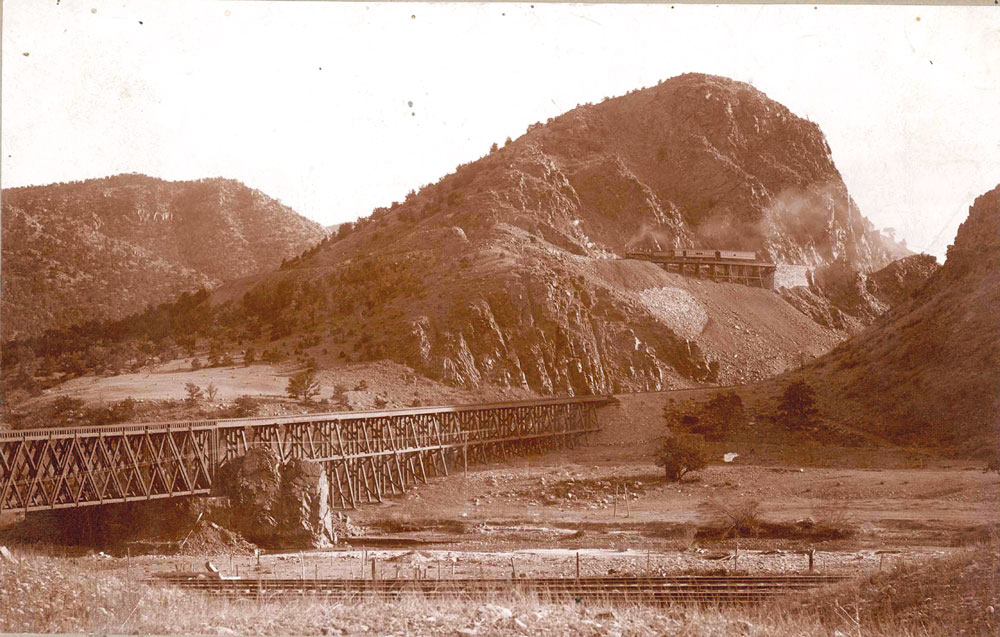

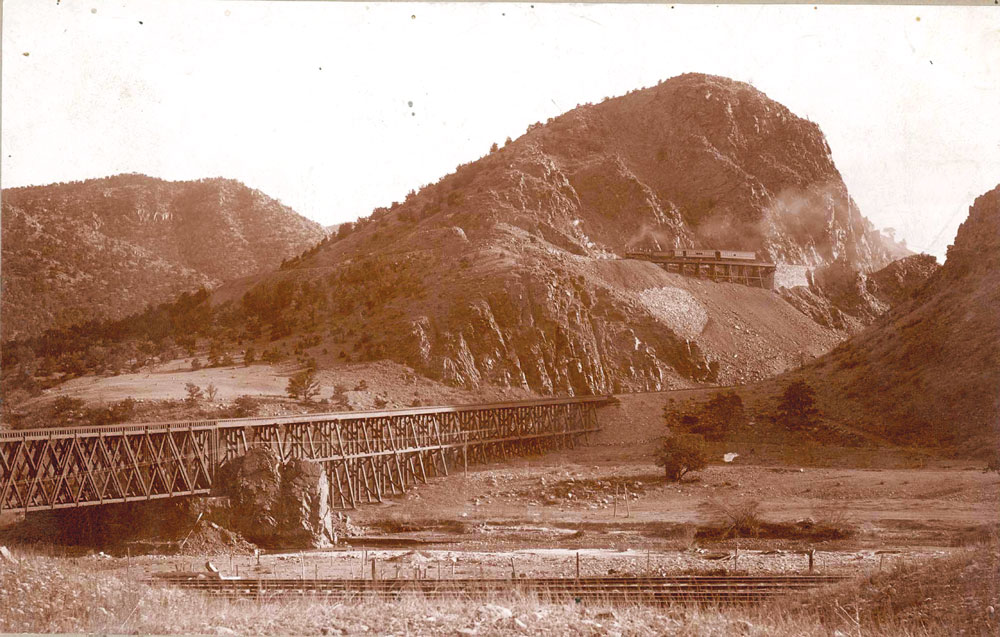

The roadbed is still fairly easy to follow from the site of the original bridge over the Arkansas (648 feet long and 95 feet high), to the beginning of the loop. It was designated 184A since it was 184 miles to Denver. U.S. Highway. 50 went under this bridge and it was a usual wayside photo stop.

From the bridge, the line followed the left bank of Texas Creek. At first it was easy for the engineers to maintain a good 2.25 or 2.3 percent ruling grade until the valley became too steep. That’s when they conceived of the idea of a loop around the pinnacle to reach the easier valley meadows above. It’s a so- called “lariat” loop because it loops back on itself and is pinched at one end.

It is still easy to see the loop coming back around far above the station site. Also, concrete reinforcement is quite visible as the line winds around the pinnacle. What an engineering feat it was! Track clung tenuously to the east slope of the valley. Roadbed was blasted out of sheer cliff faces. Trestles were built and stone retaining walls were used in a dozen locations.

It must have been quite a sight for passengers as a train rounded “Inspiration Point” with a view looking down below to Texas Creek station, the Rio Grande main line and the Arkansas River. I’m told parts of it can be walked, though we were happy just to view it from below.

[InContentAdTwo]

This Texas Creek extension was truly an engineering feat in 1900. It was costly too, at $580,000. Clearly it was made to last and was built with standard gauge rail (56 1/2 inches between the rails). The rail itself was heavier than usual for that era, 65 pounds to the yard. More common today is 131 pounds to the yard or more, but it was heavy for that time.

Congratulations were in order for the firm of Orman, Crook and Company. Apparently James Orman, with Scottish/Irish engineering background, did some or all of the work himself. It was a happy day when mixed trains 19 and 20 begin regular daily service (except Sunday) between Westcliffe and Cañon City.

Of course, mixed trains with their unpredictable schedules led to some complaints, but it was better than no service at all. By 1914, the Rio Grande gave in and put on a scheduled passenger run, never profitable for a side extension. Still, I’ve a soft spot in my heart for the mixed trains of the past. Just the thought of mixed trains brought up some memories for me.

As a kid brakeman on the Burlington Railroad I got to work a mixed train a few times. They were the odd ducks of railroading, and guaranteed a little overtime on the time sheet.

The mixed train would pick up and set out cars along the way and you’d get to see some plains towns up close. Most interesting of all, you’d also haul passengers usually to the next big town. The fare in my day was something like 55 cents. It was quite an affair, but very unpredictable as to time. One can see why the locals in Westcliffe agitated for a dedicated service.

But odd things would happen on a mixed. One day we stopped to set out a car and the conductor walked up to the little store. After an hour he returned gallantly helping a lady in her forties wearing a summer dress down to the tricked-out, mixed train caboose. She was our only passenger and I remember she shared cookies with us. One can only hope the Texas Creek passengers were that nice.

Various rail writers have speculated about why such an impressive and expensive branch line as Texas Creek happened at all. One reason was that the older Grape Creek extension, completed in 1881 had been abandoned. The Grape Creek branch, built from the mainline up to Westcliffe, had been a disaster for the Rio Grande. The creek regularly overflowed and wiped out the tracks. The last straw happened in 1889, when five miles of track were wiped out, stranding 26 miles of good track and much rolling stock at Westcliffe. The extension at Grape Creek had never been well engineered either. It was narrow gauge (36 inches between the rails) had light rail (30 pounds to the yard) and a hefty ruling grade of three percent.

There were political reasons to build rail to the Wet Mountain Valley too. Riches in mines and cattle found there had long been prized in Colorado. The mines at Rosita, Querida, along with Gyser and Racine Boy, were top producers in the state. But the residents there felt left out of state politics. In territorial governmental days, a variety of fairly ineffectual men held the governor’s post. This led to discontent with Denver as the capitol.

Governors Alexander Cummings and Edward McCook were possibly corrupt and certainly inept. That led many to suggest places like Silver Cliff as a new “start over” state capital. After all, Denver was not the only town in the game. Silver Cliff mushroomed to Colorado’s third largest city by 1880 with a population of 5,040. They did have a claim on being the state capital. General William J. Palmer, owner of the Rio Grande, paid attention to the riches at hand.

By 1880, Palmer was ready to extend his empire. Indeed, the road had just been given back to him after languishing under court supervision for some time. Leadville was now a possible plum at the top of his ruling grade. As Meredith Wilson, railroad writer of the time, put it: “Leadville is only an ornate vestibule to a great mineral kingdom beyond.”

General Palmer did not stint on building feeder lines of which the Grape Creek line, and later the Texas Creek line to Westcliffe, was one. His philosophy was, “(it is) wise and profitable to keep the main stems through all this gold and silver belt extended well ahead.”

Another reason for the line was the longtime friendship between Palmer and Dr. William Bell. Bell owned land near Westcliffe and was probably the reason for the line stopping there and not in the more prosperous Silver Cliff.

Changing times did eventually doom the line. The Rio Grande motor coach company supplied more timely passenger service. The Rio Grande motor truck service handled most light freight. Full carload trains were operating only about once a week by the 1930s. By 1937 it was clear that rubber wheels were taking over from steel wheels; the last train rolled that year.

We continued our trip all the way up to Westcliffe. The rail roadbed was often clear to see and the auto road is built over much of it. On arrival in Westcliffe, visitors will notice the old D. & R.G.W. caboose painted in Rio Grande yellow. It sits right on West Main Street and seems almost ready to roll again.

The little museum established by All abroad Westcliffe is definitely worth a visit. It’s located in the last single-stall engine house still standing anywhere. On display is a section car once used to maintain the line. Many other items of railroad interest are to be seen. There’s even a Google Earth landsat of the whole Texas Creek line. There are a number of old maps, advertisements and timetables in the museum too. One day we may be lucky enough to visit the old station. Now privately owned, it might be turned into a museum.

But even if one doesn’t get to Westcliffe, a journey to see the Texas Creek loop is well worth it. It’s a must for anyone interested in our railroad heritage and the history of Central Colorado. g

Forrest worked on the railroad as a brakeman and served two terms as a county commissioner. Which did he like more?