by Virginia Simmons McConnell

Part 1 of 2

Romantic as tales of gold and silver discoveries may be, the history of mining in Central Colorado has its grimier chapters. Many tell us how people of this area once earned their livelihoods, producing materials that fed a steel mill.

In these stories, Central Colorado has strong links with the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I) and its steel mill at Pueblo. Physically and symbolically, products from mines flowed downhill to Pueblo for a little more than a century. And, incidentally, with water capturing the spotlight today, let’s not forget that in 1905 CF&I acquired rights that moved water downhill to its steel mill from Sugar Loaf Reservoir — later called Turquoise Lake.

Central Colorado possessed supplies of coal, iron ore, limestone, and fluorspar that were of value for the Colorado Coal and Iron Company (CC&I) and its successor, CF&I. Although the mining of coal, iron ore, and fluorspar and the quarrying of limestone for CF&I had economic importance in this part of Colorado, these materials were not sufficient in quantity to last as long as CF&I needed them nor to compete in cost with products from other more plentiful sources.

CC&I began to purchase products from some of Central Colorado’s mines and quarries in the 1880s. After John Osgood and his Iowa group acquired CC&I in 1892 and changed its name to Colorado Fuel and Iron Co., CF&I bought many, but not all, of CC&I’s mine properties and continued to send most of their products to the mill at Pueblo.

After major transfusions of capital by Gould and Rockefeller interests in 1903, the steel mill grew as a regional industry, employing 10 percent of the workforce in Colorado it is said, but, at a distance from mineral resources and markets, the company never reached the size of steel mills in the East and the Midwest or, later, the West Coast.

Early in Colorado’s mining days, prospectors and miners were aware of coal and used it, wherever it existed, and so did blacksmiths who appreciated the higher heat created by burning coke. Coal’s importance soon grew as wood from forests vanished into mine timbers and buildings, the furnaces of smelters and steam locomotives. Because of the need for coal, a symbiotic relationship between railroad transportation, the steel industry, and coal mining was spawned as soon as narrow-gauge railroads could thread their way into the mining country.

Despite their chronic shortage of capital, the founders of the Denver & Rio Grande Railway (D&RG) entertained the ambition of developing a steel industry, and to that end they organized the Colorado Coal and Steel Works Company and CC&I in the 1870s. The D&RG’s first spur ran to a coal mine on Coal Creek near Cañon City in 1872, and CC&I began to produce nails, pipe, and rails sporadically in the early 1880s on the south side of Pueblo.

Although not as important in the long view as the coalfields around Trinidad, Walsenburg, and Cañon City, or in the northern field around Louisville and Erie, coal mining in Central Colorado played an important role for a several decades. Coal mining was taking place near Como by the 1870s as was small-scale coal mining near Crested Butte in the late 1870s. Beginning in 1881, production stepped up at Crested Butte and its surrounding area. Here there was both anthracite (hard coal that was desirable for domestic fuel) and bituminous coal (roasted to make coke for smelters and for the steel industry). In 1881 the D&RG built an extension into Crested Butte from its Marshall Pass Branch to access its traffic. While Crested Butte saw the largest and longest-lived coal-mining activity in the district, some also took place nearby at Floresta (formerly Ruby), Anthracite, and Elk Mountain.

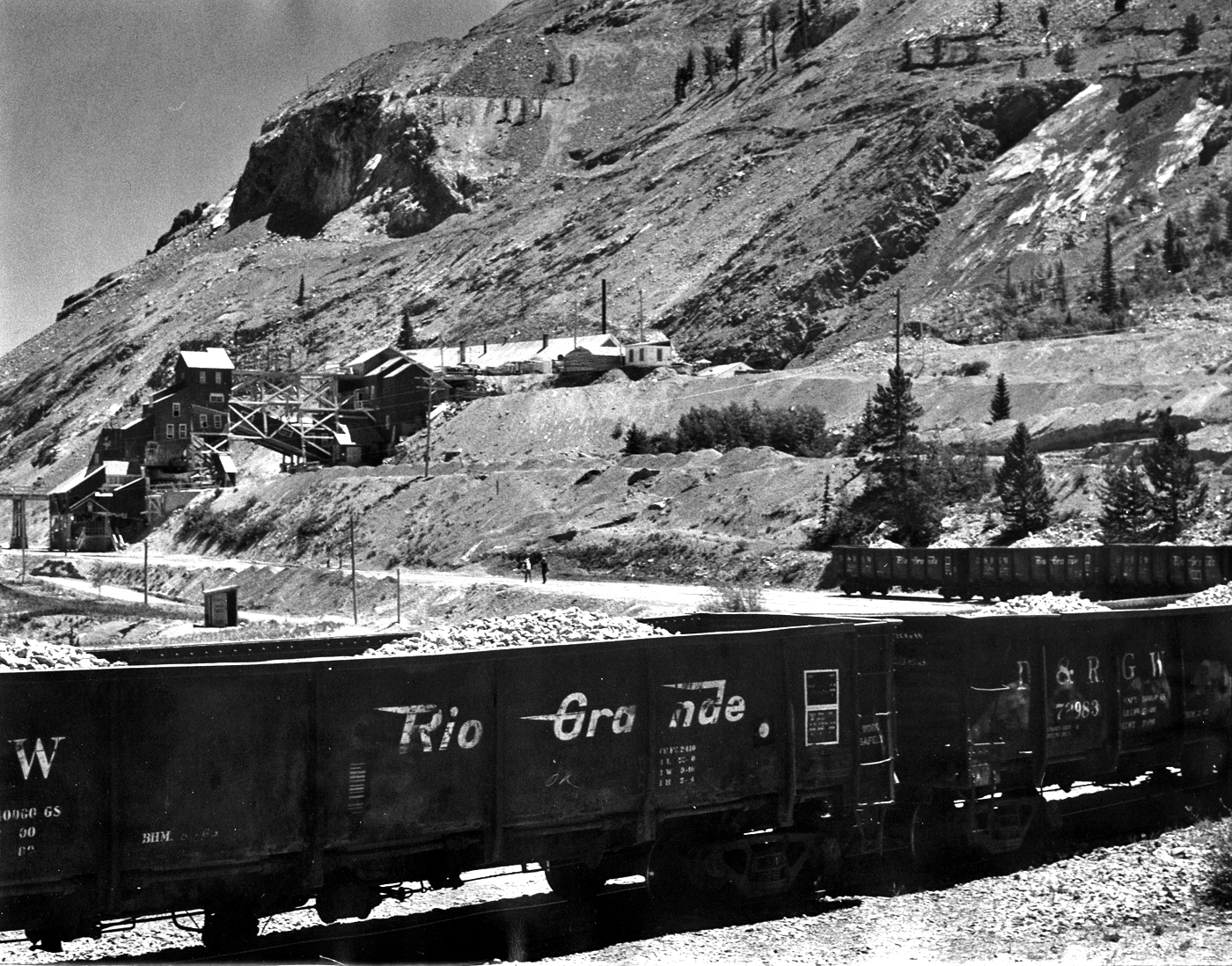

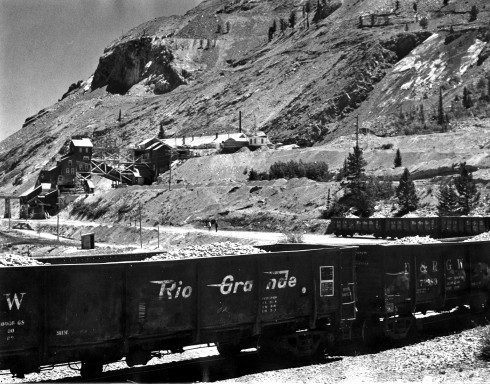

For nearly three quarters of a century, the D&RG would pull coal cars across Marshall Pass to Salida and from there to Pueblo or the Leadville area by standard-gauge, with the transfer increasing freight costs for the railroad and CF&I alike. Mules pulled coal in rail cars directly from mine openings to beehive-shaped coke ovens, where coal was roasted to drive off the moisture content, work that created many jobs while fouling the air horrendously. Coke was used at CF&I, and it also had a market at smelters in the upper Arkansas River area, especially at the Ohio and Colorado Smelter at Salida from 1903 until 1921, when that smelter shut down. At Pueblo, the need for coke from beehive ovens was declining already, though, because the plant installed more efficient by-product ovens at Pueblo in 1918 that yielded better coke.

As a coal-mining community, Crested Butte had not been a typical company town like those found in southern Colorado. Through its Sociology Department, CF&I introduced a system dubbed “welfare capitalism” by cynics. By building houses that were rented to employees, opening stores and boarding houses, and providing social facilities and medical care, the innovations improved living conditions in many places, but were resisted by some miners. At Crested Butte, local businesses, churches, and homes already existed when CF&I ownership began. Miners — mostly from the British Isles with some Slavs and Italians — lived in their own houses, too, after the company built some houses. CF&I also brought in the Colorado Supply Company’s store, a CF&I subsidiary. The store remained in Crested Butte until mining ended, whereas other company stores at Anthracite and Floresta, in 1893-1906 and 1893-1920 respectively, had shorter lives, reflecting their briefer mining activity. The Supply Company at Crested Butte also contracted with an operator to run a boarding house for single men who worked at the 150 or so coke ovens.

Underground coal mining was dirty, dangerous work with constant threats from explosive gases and rock slides as well as the long-term effects on miners’ health from bad air. The first underground accident in the area took 17 lives in the 1880s. Grievances about conditions, working hours, and pay led to several strikes over the years, sometimes in sympathy with those in other districts and parts of the country, but at Crested Butte they did not reach a level of violence like southern Colorado’s.

In 1952 the Big Mine at Crested Butte closed, and in 1955, long after revenue on the branch had sunk to red ink for the D&RG, rails over Marshall Pass were pulled up. Contributing to this finale was the development of coal mines around Somerset, where the D&RG’s extension from Delta provided a better connection to the main line for competitors. Except for the snow, the Crested Butte of today bears almost no resemblance to the coal-mining town of yesterday.

This mining saga can be repeated with variations about the mining of other products for CF&I in Central Colorado. Most of these other stories were not as long as coal mining, however, and the operations were smaller.

A primary commodity for the mill at Pueblo was iron, of course, which, ironically, was not abundant in Colorado. The CF&I mill depended mainly on ore from other states — first New Mexico, next far-off Mexico, and lastly Wyoming. After 1919, the principal source of iron was the Sunrise Mine in Wyoming, and by the 1940s CF&I was using Wyoming ore exclusively.

Some sources were found in Central Colorado in the early 1880s, though. A small amount came from precious metal mines at Leadville, and a little was found in the Grayback District near La Veta Pass. More came in magnetite at Calumet.

In 1881 Calumet and its neighborhood had the young town of Salida all fired up with enthusiasm, but, truth to tell, there proved to be more excitement than profit. Ore from Calumet and the nearby Hecla operation was brought down on an eight-mile-long spur of the D&RG to Hecla Junction in Brown’s Canyon, north of Salida, on daunting grades of seven and a half percent and six percent. The value of the iron ore, even with a little fluorspar, copper, and nearby gold thrown in for good measure, did not justify rebuilding the line after a flood took out the spur in 1901.

Next month: Orient City, Wagon Wheel Gap and the Monarch Quarry.

Historian-author-octogenarian Virginia McConnell Simmons claims that staying active makes it harder for the vultures to land …