PERCHED UP ON A HILLSIDE, barely visible from Highway 285, rests the historic Centerville Cemetery off a dead-end county road. Known as Chaffee County’s oldest burial ground, it holds 350 overlooking the beautiful Sawatch Range’s southern tip.

Nowadays, it’s hard to imagine that peaceful site contains the remains of many who participated in the deadly “Lake County War,” which began on the night of June 17, 1874, and culminated in numerous deaths. According to an August 2014 Colorado Central Magazine article by the late Charles F. Price, “At least ten and perhaps as many as a hundred individuals — no one is sure of the number — died during this struggle between 1874 and 1881, some lynched, others shot and some as a result of the shock and grief resulting from the violence.”

With the 150th anniversary of the deadly conflict looming, some might wonder why it is known as the Lake County War and not the Chaffee County War? Chaffee County was carved out of Lake County in 1878. The Colorado State Legislature created the original 17 counties in 1861, and as Colorado’s population increased, additional counties were established to better manage each locale. This caused Lake County to lose land to 6 other counties before Chaffee County was even created.

Much has been written about the war with no firm conclusion. In summary, the matter began when local rancher George Harrington was shot and killed on his property by unknown parties while trying to put out a mysterious fire in one of his outbuildings. His property fronts Highway 285, and some of the original buildings still stand.

While he and his wife Helen tried to quell the flames, Harrington was shot dead through the heart by persons unknown. Frantically dragging her husband’s body out of the flames, Mrs. Harrington then rode three miles until she found Constable Frederick Bertschy to report the ambush. George Harrington was buried in the Centerville Cemetery, located just 2 miles south of his home.

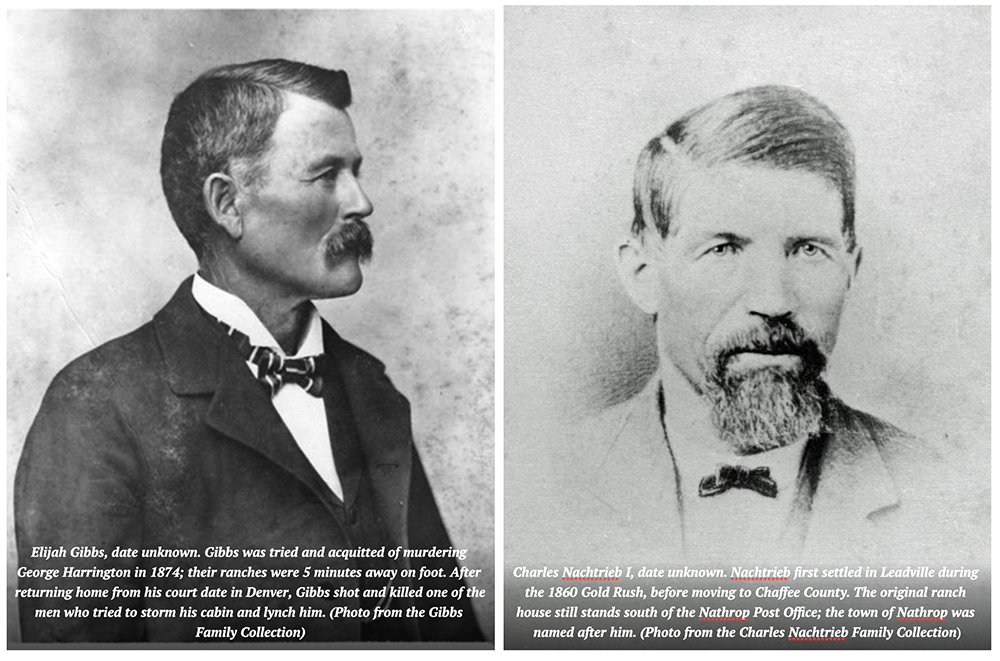

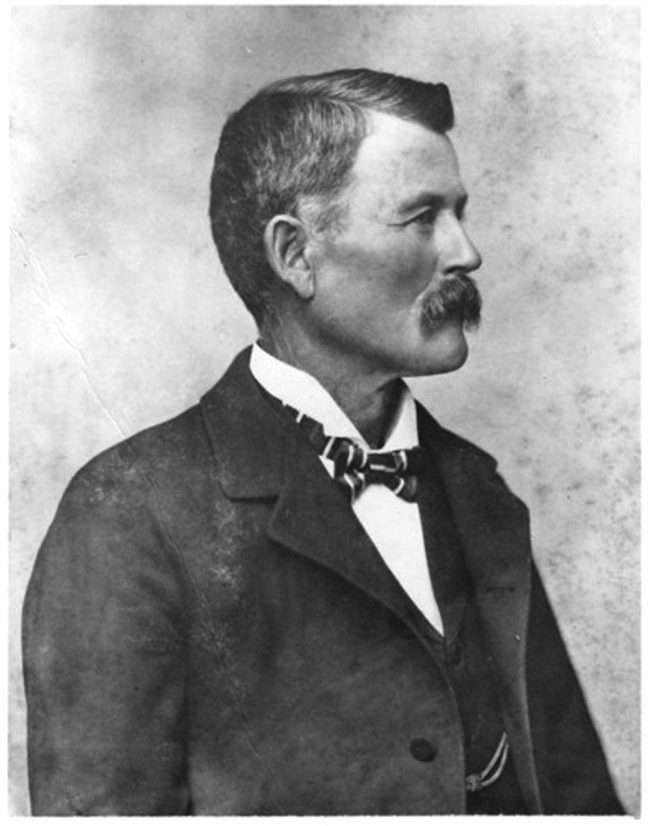

Harrington and his neighbor across the road, Elijah Gibbs and his ranch hand, Stewart McClish, had previously disagreed over a water ditch that divided their two properties. In November 1874, Gibbs and McClish were charged with murder and taken to Denver for trial in hopes of seating an impartial jury. The location change worked as both were acquitted. Gibbs promptly returned to his ranch, whereupon some citizens calling themselves the Committee of Safety, felt they should hand down what the Denver jury did not — a death sentence.

To that end, on the night of January 22, 1875, a band of 15 committeemen approached Gibbs’ ranch house while his family (including his pregnant wife and the Gibbs’ children) and several visitors (including one other child) were inside, intent on setting his house on fire to lure him outside for a lynching. However, Gibbs was forewarned and well-armed — he killed one Samuel C. Boon, while friendly fire mistakenly killed his brother, David C. Boon. Gibbs wounded several other men.

Gibbs escaped and local Justice of the Peace A.B. Cowan ruled that Gibbs acted in self-defense and dismissed all charges. Gibbs then absconded to Denver with several friends until the Chaffee County atmosphere cooled off enough for him to return home.

Many residents began taking sides with the Committee of Safety, as noted above, banning together against Gibbs. The Committee called men who stood with Gibbs “the Regulators,” although they did not refer to themselves as such.

Newspaper articles from around the state reflected the growing conflict with titles such as “Mob Law in Chaffee County” and a “Perfect Reign of Terror.” Letters to the editor refuted one story after another until it was almost impossible to determine the number of people involved and who was on which side. It was a time of lawlessness.

Those who were even remotely acquainted with Gibbs were terrorized by the Committee of Safety, with firsthand accounts of late-night inquisitions, quasi-hangings and road patrols. The tragedy culminated with the murder of Probate Judge Elias Dyer in the neighboring town of Granite on the morning of July 3, 1875, where he was shot dead in his courtroom. Dyer had been a Gibbs’ supporter but no one was ever charged with his murder.

APPROXIMATELY 14 LAKE COUNTY WAR participants are buried in the Centerville Cemetery, part of the cemetery’s history, which reveals the lives of local residents from the 19th-century — ranchers, women homesteaders, miners, storekeepers and all the other trades of the time.

Centerville Cemetery’s burials were documented by the late local historian June Shaputis in her excellent 1995 book, “Where the Bodies Are,” along with the county’s other cemetery interments. This burial ground was also known as Brown’s Cañon Cemetery, established in approximately 1865. The land was donated by Fred Bertschy, who was involved in the Lake County War as the local constable. The first burial was that of Judge Galatia Sprague’s son, William, who died in 1865 at age 15. Unfortunately, his sister followed suit 10 years later, passing at age 9. The Judge, who died in 1904, was labeled as one of the Regulators.

Those reportedly involved in the War included Andrew Bard, George and Elizabeth Bassham, Frederick Bertschy, Jacob Cantonwine, John D. Coon, Jacob Ehrhart, Griffith Evans, Thomas C. Fletcher, George Harrington, James Harvey Johnston, William Kraft, Helen (Harrington) Land and Judge Galatia Sprague.

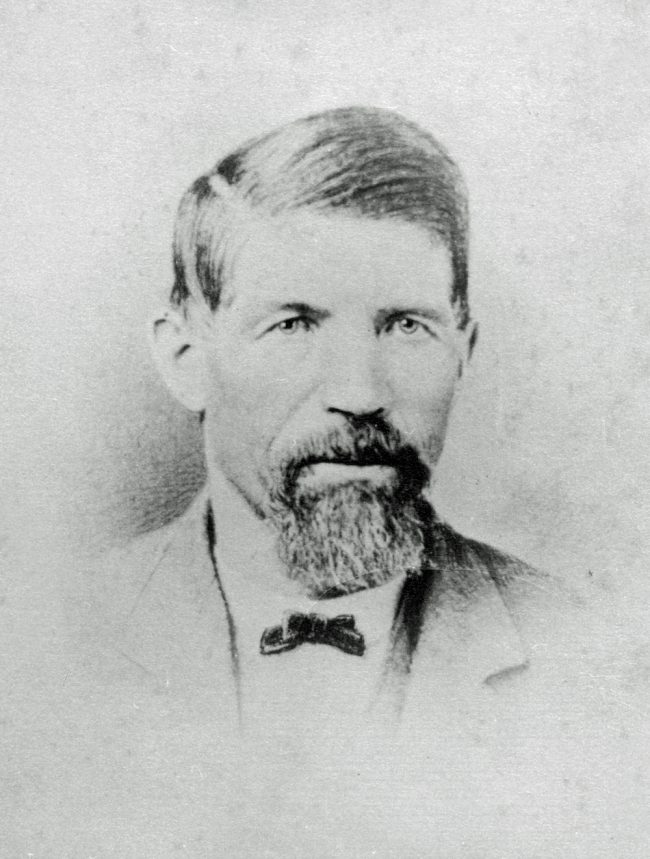

Other participants were buried in various Colorado cemeteries — Judge Elias Dyer in Castle Rock, the Boon brothers in Poncha Springs, Charles Nachtrieb I in the Nachtrieb Family Cemetery in Nathrop, Hugh Mahon in Buena Vista, and Elijah Gibbs in Oregon.

Descendants of some participants remain in the local area and have provided insights about the War. In a recent interview with Art Hutchinson, whose third great-grandfather, John McPherson, played a role in the war, said, “The relevance of the War was not who shot Harrington. That can never be proved. If the Lake County War should have significance, it’s over the fact that we have homesteaders trying to protect a right that wasn’t really codified at that time. It was probably the first or one of the first water disputes in the history of Colorado and it wasn’t even a state.”

At the time of the hostilities, water was scarce. Homesteaders were trying to eke out a living in a desert. Hutchinson continued, “In that time and place, people figured if you had done the work to get a ditch and put it to use, you were entitled to use it.” This idea reflects Colorado water law today: first in time, first in right. The dispute over water, combined with “the fact that a few people died in a little faraway place from Denver” yet received the attention of the territorial government, shows its importance. (Denver detective David J. Cook, was dispatched to Lake County by Acting Governor Jenkins consequent to the appeal of Judge Dyer after his son’s murder.) In the Lake County War, “Mostly sodbusters with little more than a log cabin and a few rhubarb plants were fighting over something that’s following us right now.”

Many historians with roots in Chaffee County spent thousands of hours researching the Lake County War. Art’s father, Dr. Wendell Hutchinson, was among them. Others included John Ophus, Ed Quillen, Donna Nevens, Dr. Fred R. Paquette and Charles Price.

Judy Starbuck, sister of the late Dr. Paquette, said, “Fritz was always, always so interested in local history, and since the Paquette family settled in the Centerville-Buena Vista area, it was natural for him to be drawn to this particular Lake County War conflict, and it became an obsession to him. It obviously was an important part of his life over many years, judging from the boxes of folders, photocopies, newspaper articles, and other information that he had gathered over those years. He spent countless hours picking people’s minds — Donna Nevens, John Ophus, and Dr. Hutchinson in particular — who shared his passion.”

Dana Nachtrieb is a fourth-generation Chaffee County resident descended from Charles Nachtrieb I, who immigrated from Germany in the 1800s. The town of Nathrop was named after Charles, who established a mill, a hotel and other businesses there. Many people had trouble pronouncing his last name, especially the local Utes, so the name morphed into Nathrop. Charles’ original house still sits along County Road 286, just south of the Nathrop Post Office; a photo of the original buildings and mill is the cover photo on Where the Bodies Are. The Nachtrieb family has not lived in the house since the 1930s.

Regarding the Lake County War, Dana feels that people tended to exaggerate stories from the 1870s and that published books on the matter are a more reliable source of information rather than some of the historical newspaper articles.

The 1881 murder of Charles I is frequently considered the last death related to the Lake County War. Reportedly involved as a Harrington supporter, Charles was shot and killed in his store in 1881, allegedly by a cowboy named Bert Remington, who was never apprehended. However, later speculation arose as to the shooter’s true identity and that the name Remington was an alias for a man related to Harrington. This man reportedly believed that Charles, not Gibbs, was Harrington’s killer and murdered him for revenge.

The violence of the Lake County War seems unthinkable today, but for reasons we may not understand today, during that time, the lethal Wild West reigned in what is now Chaffee County.