Article by Virginia McConnell Simmons

Transportation – February 2006 – Colorado Central Magazine

LITTLE TRAINS huffing and puffing across mountain passes and powerful diesel locomotives grinding across the open spaces of the West may be the images that charm rail fans. But on ledger sheets, black and red ink is the picture that inevitably decides which lines endure.

Regardless of whether it provides freight or passenger service or seasonal tourist attractions, rail transportation survives or fails on the basis of hard, economic realities, and rail service in the San Luis Valley has been no exception. Buffs of the old Denver & Rio Grande Railway will remember the founders’ contests with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe and Jay Gould’s Union Pacific, and many subsequent endeavors. Today’s competition is equally intense.

The best- known version of railroad history in the Valley goes like this: The Denver and Rio Grande Railway arrived in the San Luis Valley in 1877 because of what lay to the west, mining activity in the San Juan Mountains. Almost immediately after rails arrived at Alamosa in 1878, construction of a network of tracks began. The mining industry was the chief stimulus, but short- lived spurs to lumber camps also contributed to construction and revenue.

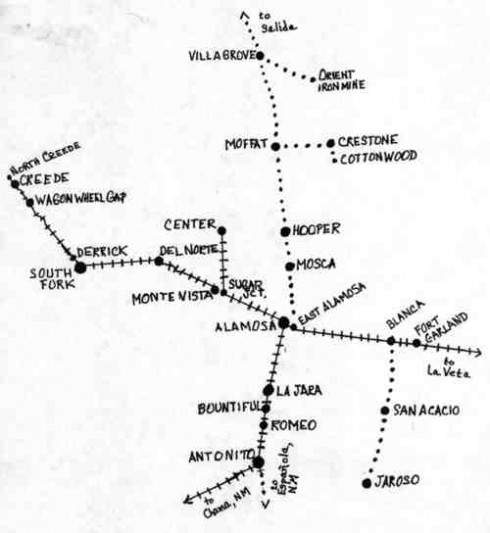

Narrow- gauge extensions quickly ran to Antonito and westward to Durango and Silverton; and to Monte Vista and Del Norte; and down to Española, New Mexico, for a connection to Santa Fe. When gold and silver mines boomed at Creede in Mineral County, D&RG rails followed, and excursionists and a fluorite mine near Wagon Wheel Gap augmented the line’s traffic.

Along the narrow- gauge line that crossed Poncha Pass, thereby connecting Salida and Alamosa, gold ore from Bonanza and iron from the Orient Mine east of Villa Grove brought in revenue. In addition to a spur to the Orient Mine, another was constructed from Moffat to Crestone’s mines and smelter in the 1890s.

By 1899 improvements were happening in the Valley as the D&RG converted to standard gauge and moved tracks a short distance from La Veta Pass to Veta Pass. The line to Creede was standard- gauged as well.

In the twentieth century, ranching and irrigated farming rivaled mining for economic importance in the region, and two independent standard- gauge short lines appeared. One of these, on the eastern side of the Valley, was the 30- mile San Luis Valley Southern Railway, which hauled vegetables in refrigerated cars from warehouses at San Acacio and Jaroso, near the New Mexico state line, to the D&RG at Blanca. The other line, the San Luis Central Railroad (nicknamed the Peavine), constructed a 12- mile- long short line to serve the agricultural area between Center and Sugar Junction, where a short- lived sugar- beet refinery had been built just east of Monte Vista.

EMPLOYMENT AND COMMERCE within the San Luis Valley thrived with the railroad, and about 600 employees worked for the D&RG. Alamosa was not only a railroad division point but also a distribution center for the area. Residents and commerce prospered with freight service as well as passenger trains east, west, north, and south. Agriculture expanded, and by 1930, according to Leland Feitz’s booklet Alamosa, 11,000 carloads of potatoes, 2,200 of vegetables, 900 of sheep, 780 of cattle, and 110 of hogs moved out of the Valley. Double- decker cars hauled livestock, and large volumes of wool went to market.

Hard as it may be to believe, at one time more livestock was shipped from Moffat than from any other rail point in the state. Hay was also exported in large quantities — back in that time when there was more water for irrigation, as rancher- historian Virginia Sutherland points out.

As the 20th century progressed, the growth of trucking brought many changes. By the latter part of the century, livestock was being shipped by truck instead of by rail, and shippers of vegetables such as lettuce, spinach, and carrots were also turning to truck transportation, which could deliver produce to markets more quickly.

RAIL TRANSPORTATION DECLINED for nonperishable commodities as well. As the value of precious metals fell, shipment of silver ores declined and then stopped by the 1980s. As manufacturers shifted from wool to synthetic fibers in their products, especially carpets, large flocks of sheep, once so common in and around the Valley, became a rarity. Such industries no longer required rail service, and the railroads gradually shrank.

Not surprisingly, the first to go were the narrow- gauge branches, although some hung on for a long time with three rails accommodating the misfits. The never- profitable Chili Line was lopped off first, and in the 1950s the line north to Salida was abandoned. Passenger trains to Durango also stopped running, but coal- burning steam locomotives still pulled freight into Durango. Farmington’s oil and gas industry was the principal reason narrow- gauge operations across Cumbres Pass survived, but eventually that line failed, too.

When the Durango operation finally gave up the ghost, the 64 miles of track between Antonito and Chama, New Mexico, were sold to the States of Colorado and New Mexico for a tourist attraction, the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad (C&TS). In 1974 Congress authorized an independent interstate agency, consisting of four commissioners — two from each state — and an executive director to administer the property.

In addition to the loss of traffic from the narrow- gauge branches, standard- gauge service also shrank in the last quarter of the 1900s. In 1972 D&RGW trains withdrew from the town of Creede, because, with Creede identified as a terminal, crews had to be paid for two work days by union agreement. By cutting out Creede, the railroad reduced labor costs while still shipping Creede’s ore concentrates from loading docks near the Wason Ranch until the last train ran in 1984.

ANOTHER LOSS was the Southern San Luis Valley (formerly the San Luis Valley Southern), which had been reduced to a switch engine hauling Colorado Aggregate’s scoria from its warehouse to Blanca, two miles away. This short line finally quit operations in 1993/1994. In 2001 trains stopped running to South Fork after the closing of a large sawmill that had been shipping finished lumber and wood chips. Since then the tracks from Monte Vista through Del Norte to South Fork have been idle, though not abandoned.

Such changes might suggest that railroading is about to vanish in the San Luis Valley. On the contrary, a freight train rumbles into the San Luis Valley every weekday, entering and leaving at night to allow local operations to take place during the day. Agriculture still accounts for considerable traffic, although livestock has not been transported by rail for years. In the mid- 1990s, potatoes amounted to 20 carloads a day in autumn, but by then most smaller growers and warehouses were shipping their potatoes in faster, cheaper trucks. However, at that time Coors Brewery’s barley was filling 800 carloads a year.

Despite gradual reduction of agricultural shipping by rail, the independent Peavine (the San Luis Central) continues to deliver agricultural chemicals upstream and potatoes, wheat, and barley downstream to Sugar Junction, the interchange point. Figures for the growing season September 2004 through August 2005 show that the San Luis Central shipped virtually all the potatoes that went out by rail, totaling eight percent of the potatoes moving out of the Valley, or 1,421,816 hundred weight. A lot of potatoes! Weighing 130,000 pounds per carload, these were shipped from one major warehouse in refrigerator cars to Houston, primarily, where the spuds are repackaged. It is anyone’s guess at present whether recent increases in the price of gasoline, combined with chronic difficulty in finding truckers, will bring some independent growers and warehousers back to rail transportation.

[InContentAdTwo]

Local customers are located all along the tracks of the main line. Monte Vista sends hundreds of hoppers filled with the Coors Brewing Company’s barley, while La Jara and Bountiful ship smaller amounts of grain. Other rail customers along the route are the Monte Vista CoOp, businesses dealing in scrap metal and chemicals, lumberyards, and so on.

THE VALLEY’S RAILROADING still has an important tie with mining, too, although the products ceased to be precious metals quite a while ago. In the Antonito area, the largest volume of railroad traffic consists of carloads of perlite, although the number has shrunk in the past few years. Ninety percent of the perlite from the Harborlite Plant, owned by World Minerals, is shipped by rail in about 2,000 hoppers per year. The neighboring Dicaperl Plant, owned by Grefco, now ships most of a lighter- weight product by truck, however.

Near these two plants, south of Antonito, Colorado Lava loads some scoria into railroad hoppers, but this company’s large bagging facility, east of the perlite plants, has no rail spur and ships by truck. (Colorado Lava bought out Colorado Aggregate in 2000.) Trucks haul these materials — perlite and scoria — to Antonito’s plants from mines a few miles north of Tres Piedras, New Mexico. Employment at these facilities is important in low- income Conejos County.

Other activities have taken place in boardrooms. Early in its life, the original Denver & Rio Grande Railway became the D&RG Railroad when the original company went broke and was taken over by new leadership. In the 1920s, the D&RGRR became the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad (D&RGW), following corporate changes that consolidated operations in Colorado and Utah. Although maintenance had been neglected due to financial difficulties, service and finances began to slowly improve beginning in the 1930s, thanks to more efficient management, better maintenance, and faster service. After World War II, modernization of equipment began with the introduction of diesel locomotives on the standard- gauge branches.

In the late 1980s, at a time when the D&RGW was doing quite well financially thanks to efficient management and fast service, the corporate ownership cast their eyes on wider opportunities. Under the leadership of the largest shareholder, billionaire Philip Anschutz, the D&RGW merged in 1988 with the vastly larger but unprofitable Southern Pacific Transportation Company system, and the D&RGW was forced to bear the adverse costs of the Southern Pacific Line’s problems. In 1996 this operation, in turn, merged with the Union Pacific (UP) and became part of the enormous Union Pacific Railroad, which competes with another giant, the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway Company (BNSF). Meanwhile, nostalgic D&RG lovers licked their wounds as Colorado’s native railroad was swallowed up, along with its beloved logo, and we shed another tear when cabooses, anachronisms in the world of centralized operations, also vanished.

FOR ITS PART, the UP soon sold the San Luis Valley portion in June 2003. It became the 154- mile- long San Luis & Rio Grande Railroad (SL&RG), consisting of the Alamosa branch, all of the Antonito branch, and the line from Alamosa west to Derrick. (Derrick is a switch within the town of South Fork. It lies between the Rio Grande River and Colorado Highway 149, a few hundred yards northwest of the junction of U.S. 160 and Colorado 149.)

The new owner was RailAmerica, Inc., and this acquisition brought its ownership to 49 short lines and regional railroads. RailAmerica’s headquarters are in Boca Raton, Florida, a long way from the railroad in southern Colorado, but the manager/trainmaster was located in Alamosa.

The SL&RG was given trackage rights, not ownership, on the UP’s final five miles into Walsenburg. There, SL&RG loads moved on Union Pacific trackage, a very clever and transparent way for the UP to monopolize SL&RG shipping.

Ironically, a century and a quarter after the D&RG had fought to survive in its struggles with Jay Gould, the Union Pacific finally won, indirectly at least. But supposition that such manipulations would result in a leap in freight rates appears unfounded, although tariffs have been increasing annually for years (along with the rest of the nation’s economy).

On December 22, 2005, the railroad serving the San Luis Valley changed hands again when RailAmerica, Inc., sold the SL&RG for $7 million to Permian Basin Railways, Inc., a wholly — owned subsidiary of Iowa Pacific Holdings, Inc., which is headquartered in Chicago. Adding to the corporate layers that are often difficult for onlookers to understand, Permian Basin Railways is itself a holding company. The SL&RG produced $2.6 million in revenues during 2005 through September 30, according to a press release published in the Valley Courier (Alamosa) on December 23, 2005. Iowa Holdings’ president stated therein that the area “has a long tradition of rail use for bringing farm and mineral products to market.” Another reason for the sale to Iowa Pacific may be that RailAmerica was paying too much interest on debt, which was pointed out when RailAmerica sold lines in Texas and Arizona in 2004.

Besides debts and interest thereon, another expense that railroads encounter is taxes. Like other public utilities, railroads pay ad valorem property tax on real and personal property to the State of Colorado, unless the property is locally assessed. In fact, next to nothing is locally assessed since railroads, like other businesses, are constantly on the lookout for ways to reduce their taxes. As a result, structures such as depots or roundhouses have often been demolished, sold, or given away, while land and sidings along the right- of- way occasionally are leased to local users to raise a little revenue.

AT ALAMOSA, the large railroad shops have been completely removed, and the depot belongs to Alamosa County and houses social service offices. Depots at La Jara and Del Norte became town halls several years ago. In 2002 the Union Pacific donated a unique lava- rock depot, built in Antonito in 1880, to that town, which has not, as yet, found a use for its run- down, but nevertheless historic, gift.

And now for the fun side of railroading in the San Luis Valley. At least, it is fun as long as you don’t have to worry about finances and operations. The Valley has two tourist ventures that exist outside the above- mentioned conventional operations. One of these two has been functioning for the past 35 years and the other is still on the drawing board. Since 1971, Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad trains have operated each summer on the old right- of- way between Antonito, Colorado, and Chama, New Mexico, with high- maintenance, vintage steam engines for motive power and rebuilt coaches replacing the modified freight cars that were originally used by the C&TS. So much for the fun part.

GOVERNED BY THE INTERSTATE Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad Commission since 1974, this tourist attraction has been leased to a series of managers who have experienced chronic management problems and economic woes, resulting from the relatively short summer season and from the costly maintenance of the aging equipment and roadbed. The main office is in Chama, New Mexico, and that colorful little tourist town produces more ticket sales on the C&TS than does Antonito, unfortunately. A shortfall of $807,000 had accumulated for the C&TS by the end of the 2005 season, resulting in part from lower passenger traffic and in part from a shortage of funding from the coffers of the State of Colorado, which is obligated to subsidize the operation on a 50- 50 basis with New Mexico. Alas, Colorado has been unable to contribute its share lately. After the 2005 season, the most recent manager, the Rio Grande Railroad Preservation Corporation, abruptly terminated its management agreement on November 1 and offered to sell i

Whenever a suggestion is made to reduce operations, especially by withdrawing C&TS trains from the Antonito terminal, the opposition argues that Conejos County desperately needs the tourists, the income, and the employment opportunities associated with the attraction. On December 22, to everyone’s relief, the C&TS Commission announced that the 2006 season will take place again from May 27 through October 15 with no curtailment at Antonito.

In the meantime, Colorado’s Governor Bill Owens, State Senator Lewis B. Entz (R- Hooper), and Representative Raphael Gallegos (D- Antonito) were attempting to find a monetary solution — specifically $870,000 for the 2006 season — that might be acceptable to Colorado’s Joint Budget Committee and legislature.

ANOTHER TOURIST LINE is planned for the 22 miles of standard- gauge right- of- way between Creede and Derrick (South Fork). This mileage was purchased from the Union Pacific in 2001 by the Denver & Rio Grande Railway Historical Foundation. Don Shank, the foundation’s executive director, reports that the excursion line, often called informally the Wagon Wheel Gap Route, may someday be called the Denver & Rio Grande Railway, Railroad, or Western. (Shank’s explanation for suggesting the D&RG title, if he does use it, is that the UP did not purchase the corporate name.)

By any name, that excursion line is not yet running. Shank has spent a considerable amount of time and money in litigation with property owners, particularly in Mineral County, where some structures impinge on the right- of- way. But on- going maintenance work on the grade has been performed, while work on bridges awaits. Several pieces of standard- gauge equipment have been acquired, and these are presently stored on sidings near the old water tank on the east side of South Fork. The office of the Denver & Rio Grande Railway Historical Foundation is located in Monte Vista.

Railroads, history, and tourism have a longstanding symbiotic relationship in Colorado, including in the San Luis Valley. Along with several other railroad- related properties in the San Luis Valley, the C&TS is a district that is justifiably in the National Register of Historic Places. Bolstering Shank’s claims to historic significance and nonprofit status, the Creede Branch also won designation in the National Register of Historic Places in 2002. Additional historic sites along the route are a steel bridge across the Rio Grande, the privately- owned Wagon Wheel Gap depot, and the entire town of Creede. A directory of the Colorado State Register of Historic Properties with thumbnail histories of each is available on the Internet at www.coloradohistory- oahp.org.

Sentiment and pleasure aside, railroading in the San Luis Valley has had its ups and downs for nearly 140 years. There is no denying that, in the past, commodities have been more profitable than passengers, but perhaps that too will change. Meanwhile, activities in corporate board rooms have proven to be as important and interesting to onlookers as are those on the rails, once you get the hang of them.

Virginia McConnell Simmons lives in Del Norte and is the author of many books of regional history.