By Joyce B. Lohse

“It isn’t who you are, nor what you have, but what you are that counts. That was proved in the Titanic.” – Margaret Brown, The Denver Post, April 27, 1912.

Margaret Brown, wife of Leadville mining engineer “J. J.” Brown, was an outgoing woman with a lot to say on many subjects. If she had no audience, she would find one, or contact friends in the newspaper office. In today’s world, she probably would have been delighted with Facebook and Twitter. Print newspaper was the available media in the early 1900s, and she used it well. According to a Rocky Mountain News retrospective when she died in 1932, she stated that when she survived the Titanic disaster, “It was Brown luck. I’m the Unsinkable Mrs. J.J. Brown.”

After surviving the sinking of the Titanic steamship in April 1912, Mrs. Brown wished to speak out and tell her story. Unfortunately, she was not invited to present testimony at a Congressional hearing attended predominantly by male survivors. She was angry and deeply frustrated. When she put out the word in Denver that she had the inside story to tell and she was ready and willing to share it, delighted journalists snapped at the bait.

Margaret “Maggie” Tobin, who grew up in a poor Irish family in Hannibal, Missouri, was never referred to as “Molly” during her lifetime. Margaret was a tomboy who enjoyed adventure along the banks of the Mississippi River with her siblings. When her grown sister, Mary, left with her husband in 1883 to seek their fortune in Colorado’s mining camps, Margaret yearned to follow. Her straight-laced Catholic parents kept her at home until she turned eighteen, then allowed her to follow her sister to Leadville. When her brother, Daniel, arrived soon afterwards, the curvy, redheaded teenager went to work taking care of her brother’s cabin and cooking meals. Soon after, she obtained a job at Daniels, Fishers, and Smith’s Emporium selling dry goods.

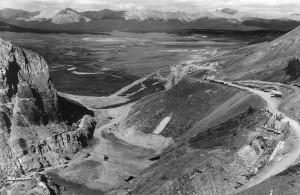

Although the gold rush of the 1860s had played out, the silver rush of the 1880s built Leadville into a wild and prosperous boom town. Margaret envisioned finding romance with a wealthy mine owner. In addition to a luxurious future, she hoped to provide comfort for her parents in their old age.

Margaret found love instead of wealth when she fell hard for a handsome mining engineer named James Joseph “J.J.” Brown at a Catholic Church social. According to the Denver Post in 1912, she said, “Jim was as poor as we were, and had no better chance in life. I struggled hard with myself those days. I loved Jim, but he was poor. Finally, I decided I’d be better off with a poor man whom I loved than with a wealthy one whose money had attracted me. So I married Jim Brown.” They were married on September 1, 1886 in the Church of the Annunciation in Leadville. She added, “I gave up cooking for my brother, and moved in to Jim’s cabin, where the work was just as hard.”

During the next seven years, while J.J. put in long hours in the mines, Margaret kept up their cabin home in Stumpftown in the mining district. After their son, Lawrence, was born in 1887, they moved to a cottage in nearby Leadville. In 1889, they had a second child, Catherine Ellen, called Helen. Although Margaret had her hands full with two children, she was interested in mining and learned all she could about it. Later, she would say, “And them was the happy days.”

1893 was a tough year for Colorado and the nation. When the Sherman Silver Mining Act was repealed, gold was chosen over silver to back American currency. The price of silver plummeted, fortunes were lost, and the silver industry fell into a deep slump.

J.J. Brown, who was working for the Ibex Mining Company, developed a new process to strengthen mine walls using hay bales. When this new method was implemented in the Little Jonny Mine, a formerly overlooked gold strike was discovered. With J.J. as 1/8th owner, it became one of the largest ore strikes ever found in the district.

The Browns were suddenly wealthy. A year later, they purchased a mansion in Denver, followed a few years later by a farm with a country house built by J.J. outside the city for holidays and weekend get-aways. Margaret embraced city life and stayed busy taking care of her family, attending the opera, and working on charity benefits.

While the Browns supported the building fund for the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, J.J. continued his mining interests in Leadville, and helped fund its Ice Palace. Built in 1895, the ice structure was meant to attract tourist money to Leadville during its struggle to recover from the silver slump. However, an early spring thaw put an untimely end to the ice palace as a fund raiser.

Margaret continued to care for her family into the 1900s. She had accomplished caring for her parents into their old age, until they passed away. When her brother Daniel’s wife passed away, she took in their three daughters to raise as her own.

While her children attended school, Margaret worked to improve her own literacy. After a Denver newspaper reporter ridiculed her use of grammar, she studied hard to improve it, and she read voraciously. She learned new languages and developed a strong desire to travel.

After J.J. Brown suffered a mild stroke, his behavior became erratic. He disappeared for long periods of time, and acted as if he had never been absent when he returned. His “business trips” became more frequent, which left Margaret distressed and heartbroken. Margaret dismissed questions about their separation, sought a change of scenery, visited Newport on the East Coast for longer periods, and travelled.

While sightseeing in Egypt, Margaret Brown received a message that her little grandson was ill. She decided to return home at once, to learn his condition and offer support. Her daughter, Helen, who was studying in Paris, had a ticket to return home aboard the Titanic on its maiden voyage, which she offered to her mother. Margaret gratefully accepted it.

On April 15, 1912, the unsinkable new steamliner, Titanic, sank to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean following a collision with an iceberg. Margaret Brown was one of the passengers who survived the tragedy. After the disaster, Margaret Brown had her say.

Margaret Brown spread her story to other newspapers as well. Recalling her departure from the Titanic for the Denver Post on April 19, 1912:

While aboard the Carpathia, Margaret Brown started a survivor’s fund, collecting $10,000 before she left the ship. The money helped care for those who lost their families and all their belongings when the ship sank. Many immigrants could not speak English, and she used her language skills to comfort them, help them make plans, and to send messages to their families back in their homelands.

Once Margaret Brown returned to Denver, she answered questions for an anxious community starved for every detail she could share. At a lunch hosted by Mrs. Crawford Hill, famous for the exclusivity of her Sacred Thirty-Six social clique, Margaret was guest of honor. The guests hung on her every word, and she basked in the attention, although it was by no means her only social achievement in Denver.

For some people, life after surviving the Titanic disaster might have diminished and taken on a lack of importance. Not so for Margaret Brown. The next twenty years were full of activism and issues she considered important. Her Titanic fund helped other Titanic survivors, helped build a monument, and recognized the heroics of their rescuers.

During a visit in Florida, Margaret again exercised her bravery. A fire broke out at the Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach, Florida, and she led other guests to safety. During World War I, she travelled to France to help the Red Cross, and made the house she used in Newport accessible to that organization. Briefly, she ran for Congress.

During the Ludlow Massacre in Southern Colorado, Margaret rallied women to provide supplies for mining families. At home, she helped her grown children and her nieces transition into adulthood. After her husband’s death, she started a feminist coalition for mining widows in Leadville. France honored her with the Palm of the Academy for theatrical excellence.

Margaret Brown had much to give and accomplish after 1912, when she survived the Titanic’s demise in the dark, icy Atlantic waters. By the time she passed away in October 1932, she was still helping others with her interests in culture and theater. At the time, she lived in the Barbizon Hotel, a residence in New York City, where she helped young women study to become actresses.

Among her varied interests, the Unsinkable Mrs. J. J. Brown never forgot her past during the Leadville mining years when she and J.J. struggled. After her death, parcels from Mrs. Brown arrived in Leadville. In keeping with her tradition, she had arranged to send packages to mining families, full of Christmas gifts of toys and clothing for their children. From beyond the grave, she once again provided for those who were less fortunate.

Joyce B. Lohse writes and researches biographies about Colorado pioneers. She can be found lurking in archives and cemeteries. www.LohseWorks.com.