Story and photos by Maisie Ramsay

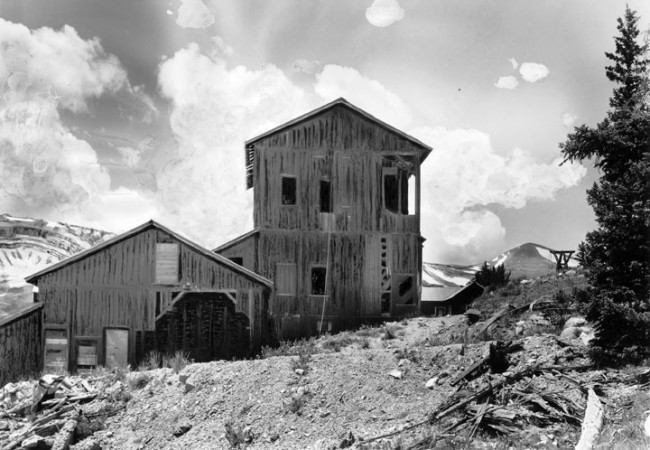

High atop the wind-blasted saddle between Mount Sherman and Mount Sheridan sits the time capsule that is the Hilltop Mine. This is not the kind filled with trinkets and buried for future discovery – no, the Hilltop Mine is an accidental time capsule, a relic of times long past, a monument to human ambition. Crack open the history books, and get a glimpse of the past.

The Hilltop Mine is now little more than a sun-bleached outbuilding clinging precariously to a 12,900-foot talus slope. The massive infrastructure that transported tons of ore has largely disappeared. What meager evidence remains is slowly dissolving into the earth.

“Some see (these sites) as a monument to history and our founding economy, others see them as an eyesore and something environmentally destructive,” says South Park historian Christie Wright. “I find them quite fascinating … but then you look at Leadville, a Superfund cleanup, and the EPA spill in Ouray. It was the founding economy of our state, both good and bad.”

The Hilltop Mine was not the Mosquito Range’s first high-elevation claim, nor the most well-known. Rather, it was among several high-elevation mines extracting precious metal from the Mosquito Range during silver boom of the 1800s.

Wright, who has written books on Park County history and is president of the Park County Local History Archives, links a single mine with the development of the Mosquito Range silver rush.

“There was a discovery at the Moose Mine, and that was the precursor to the silver rush,” says Wright. “The silver in Park County predated the Leadville discovery by several years.”

The Moose Mine proved as legendary as its namesake and precipitated the growth of other sites. There were the Russia, Present Help and Dolly Varden, to name a few. The big problem, from the perspective of miners completely devoid of modern conveniences, was the sites’ lofty elevations.

The Moose Mine was located well above treeline on Mount Bross. The Russia and Present Help mines were high atop Mount Lincoln. The Hilltop group claims reached nearly 13,000 feet.

These sites were of such lofty bearing that they became known as “aerial” mines, as the workers sometimes found themselves literally working among the clouds – the name of Harvey Gardenier’s book on the subject.

The air was thin, the weather extreme, clothing and equipment primitive. What drove men to such lengths?

“I think sometimes it’s simplistic to call it greed. The lure of something better, the promise that money could bring your family was really compelling,” says University of Denver art professor Sarah Gjertson, who has studied the Mosquito Range aerial mines for her work as an artist. “The promise of wealth draws people to do all sorts of things, even today.”

In 1873, the Last Chance lode was discovered high between the summits of Mounts Sherman and Sheridan, a thick vein of silver-rich lead ore rising from the depths of the mountain.

In addition to Last Chance, there were the Hilltop, Ptarmigan, Leslie De, Top Hill, Rush, Enterprise, Astor and Vanderbilt claims. These claims, as recounted in a 1965 Colorado School of Mines doctoral thesis by Duane Bloom, formed what Bloom describes as the “Hilltop ore zone, the most productive zone mined in the district.”

The ore was extracted, ounce by ounce, first by mules and burros, then by a 13,000-foot aerial tram.

Bloom reports the Hilltop ore “was mined continuously for a distance of over 1,450 feet, had a maximum width of 70 feet and a maximum height of 65 feet.” Each ton of ore contained 25 ounces of silver and 0.04 ounces of gold on average.

By Bloom’s account, the Hilltop shipped $675,000 worth of ore in 1888. The next year, production totalled $303,000. In 1890, that number dropped again to $150,000. Translated to today’s currency, Hilltop’s annual production ranged from roughly $17 million to about $4 million.

The ore coming from Hilltop was enough to merit a mill site on the banks of Fourmile Creek. This mill site grew into a town later named for local prospector Felix Leavick.

“Larger communities were definitely driven by the productivity, the wealth that was driven by the mines,” Gjertson says.

The same source of riches that helped found Leadville, Alma and Fairplay also created smaller, less enduring towns, Leavick among them.

Miners who worked gold and silver claims lived in camps sometimes as transient as the mountain weather.

“Even on the Mosquito Range, there are tons and tons of mining claims, but there are equally as many where there’s nothing remaining,” Gjertson says. “Sometimes it was just a handful of people living in a canvas tent while they were mining.”

When the claims were played out, the workers departed for richer fare. The longer the silver lasted, the longer the workers stayed. They were nomads of Manifest Destiny, forever on the search for a better life.

[InContentAdTwo]

The riches at Hilltop were compelling indeed. More and more men were drawn to the claim, and a town began to form around the mill site. The mill bloomed into a hub of industry, and then, a town.

Then, disaster. The price of silver began to decline, then drop, then plunge precipitously into a gaping abyss. Some blame the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, others point to enduring downward trends in the silver market. Regardless of the cause, the Silver Crash of 1893 soon took its toll. Colorado’s economy was shaken to the core, and Leavick was by no means immune.

Legend has it the entire town was evacuated overnight, its occupants abandoning Leavick like rats from the proverbial sinking ship. There are stories – possibly tall tales – that miners fled straight from the dining table without bothering to clean up, their dirty dishes left to petrify on the table.

The 1893 Silver Crash wasn’t the end of Leavick or the Hilltop Mine. An attempt was made to reopen the Hilltop Mine. In 1896, the Hilda Mining Company undertook a major rehabilitation of the Hilltop Mine, according to Bloom. A railroad line was extended 11 miles from Fairplay to Leavick. A massive aerial tram connected Leavick to Hilltop, expediting the transport of ore from the mine to the mill site.

Leavick repopulated, supporting several local businesses and, in keeping with the times, a house of ill repute.

Leavick was more than a mining camp. Whole families settled in Leavick. Students traveled by snowshoe to attend class, while women mostly kept the home fires burning. Even the U.S. Postal Service took note of the town’s newfound prosperity, opening a Leavick storefront in 1896.

It closed three years later.

Like wildflowers in alpine tundra, the blossoming of Leavick was short lived. The town followed the fate of the post office, albeit at a more gradual pace. Mining operations wound down, and so did Leavick.

There was some sporadic activity until the early 1920s, and another round of extraction in the late 1940s. As the mine lived on, Leavick became a ghost town.

Little remains of Leavick. A blacksmith shop and a homestead house were moved to South Park City in Fairplay. There, they remain preserved as relics of a bygone era. The story of Leavick was a common one in the Colorado Mineral Belt. Boom towns went bust with all the predictability of the seasons.

Despite this commonality, there’s still something captivating about old mine sites like Hilltop. They are microcosms of human endeavor: crumbling monuments to avarice, ambition and survival. Their empty buildings serve as a haunting reminder that the lives we create for ourselves are impermanent and fragile, subject to the whims of fate.

Early prospectors came to Colorado to wrench unfathomable wealth from the cold grip of the Rocky Mountains. These days, the mountains are the last place you’d move to get rich.

Indeed, it takes a special combination of grit, determination and inventiveness just to eke out a living in our rural communities.

Our present-day mountain towns offer wealth of a different variety – wealth of community, natural beauty and quality of life. Some riches can’t be measured in gold.

Maisie Ramsay enjoys life’s riches from her home in Poncha Springs, and is especially grateful for Christie Wright’s above-and-beyond assistance with this story. Follow Maisie’s frolics at theviewtax.com.