Ever since we took over the reins of this magazine last March we’d been hoping to do a profile on George Foott. His wonderfully realistic historic paintings and his legendary boating skills — skills he was still developing well into his late 60s — were an inspiration to many in a variety of intersecting circles in Colorado.

Then suddenly, he was gone, a victim of the melanoma which had metastasized and quickly took George on December 17, 2009 at the age of 70.

Rather than write a tribute to the man ourselves we sought out some of his old friends, kayaking buddies and business associates and asked them to tell us about George in their own words. We thank them for their memories and contributions. — M. Rosso

Mining District Days

by Brian Levine

I’d like to say I always knew George Foott would become a remarkable artist. But that wouldn’t be true. We knew each other for a number of years — now that I think of it — it was way back in the 1980s when we were both in Victor, Colorado, often in search of the same book, the same historic artifact. Of course, we each had our various reasons for wanting these: George for his art; me for my writing. And that, on occasion, made us competitors. I’m pleased to say we evolved out of that.

George Foott was born in Seattle in 1939, went to the University of Washington, and studied Industrial Design. Along the way, he filled his electives with art classes, history and other related interests. By 1966, George had a degree in Mechanical Engineering and applied his talents in that discipline. He moved to Denver in 1969 and became a professional designer of medical equipment. In his spare time, he explored Colorado. What else? All of its history intrigued him, especially when he could find a fragment here and there; something he could own and hold and translate into a picture.

There were times when we went on hikes together, often with friends like Ken Schneider and Owen Fuhlrodt — both antique dealers. I often exhausted George with my incessant talk and he claimed he needed others to go with us to give him a break from having to listen to me.

I lived in Victor then, and George owned a small building on West Victor Avenue. He’d come up from Denver to work on his place; and when he had time, we’d head out on the history trail. We’d hike up to the Independence Mine, or the Ajax, the Last Dollar, or Bull Hill and beyond. I’d be talking all the way — instead of listening — and George would be thinking about how to lay out a pen and ink drawing. Everything about the Cripple Creek District fascinated us, from its geology to its waste rock dumps, wood foundations to abandoned buildings, broken down ore carts to fragments of whiskey jugs; every bit a time traveler inspiring us with the resonance of past events and forgotten people.

I took to writing about Cripple Creek and its maturation from mining camp to gold district. George expressed his passion for the place and its history in drawings and paintings. But what thoroughly ensnared people such as George and myself was anything that excited, alluded to, inspired and promoted our romanticized visions of gold and silver mining in nineteenth-century Colorado.

Take the miner’s candlestick as an example. It was an early form of lighting in underground mines. At first, it was simply a utilitarian object; but over the years the candlestick became fancy, more elaborate, and a thing of pride. Its history became one of George’s first inspirations. Not just any old plain sconce; but rather, the fancy and unique candlesticks forged by true craftsmen of the time. George must’ve seen a bit of himself in each of the original candlesticks he owned because each showed up in one of his works. In fact, they appeared in some of his first pen-and-ink drawings. He made cards with their images, and prints, and then full-fledged mining scenes. George even fashioned shadow boxes around his favorite candlesticks, and then, in his distinctive calligraphy, recorded the history of each on the matting around it.

Head frames and sheave wheels, ore carts and old wooden buildings were next; then there were railroad trestles, locomotives, stations and more. In 1990, George took up oils and used that medium to add color and depth to his artwork. Nine years later, George retired from his engineering career, sold his homes in Littleton and Victor and moved to Salida, and there, with his wife Shirley, continued to explore the Colorado Rockies and further develop his themes and painting style.

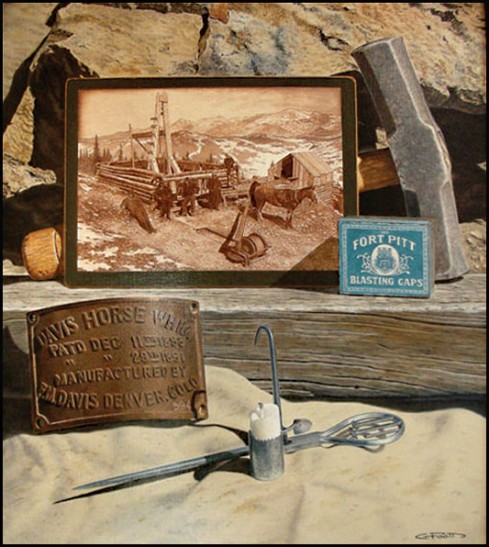

A certain type of still-life, photo-realism took hold in his artistry. Not only did George get his inspiration from old photographs, usually albumen cabinet cards, pre-1910, by William Henry Jackson, Edgar Yelton, and A.J. Harlan; but, his paintings gained dimension and shadows, and a sense of actual existence.

William Michael Harnett (Irish-born American Painter, 1848-1892), was one of George’s most powerful influences, and he regularly incorporated Harnett’s trompe l’oeil into his later paintings. No question, George’s work fools the eye; not only because original photographs and magazine illustrations appear in his paintings, but also because George was able to paint them so life-like you believed you were holding those artifacts. George’s passion was beautifully reflected in his work. He melded realism, history and emotion into astonishing, thought-provoking paintings. The results make you wonder if you’re inside the painting or out.

During his last year, George spent a lot of time improving his ability to make rock surfaces and minerals come to life on his gesso-coated, masonite board. The more he was intrigued about geology and minerals, the more he focused on reflecting his character in those painted images. He was quite proud of the porphyry and phonolite he perfected in his painting, Davis Horse Whim, which portrayed not only his interest in minerals, but also his never-ending obsession with the Cripple Creek District. He finished this painting months before the cancer claimed him.

George Foott’s work has been recognized by numerous organizations, exhibited in venues from Wyoming to Arizona, and awarded honors in Colorado. But George doesn’t have to be concerned about continuing his quest for the most emotive still life; he’s in every object he ever collected, every drawing he ever drew, and every painting he ever painted.

What’s more, I’m damned sure George just got another Cripple Creek book I’ve been searching for for ages.

Brian Levine, writer, collector, victim of numerous acronymic ailments, was born in Denver and moved to the Cripple Creek District in the 1980s. After writing several histories on the Cripple Creek District and developing his business, Mt. Gothic Tomes and Reliquary, Levine divided his time between Colorado and Scotland. Today, he writes both fact and fiction, and has acquired obsessive interests in the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald and quantum mechanics.

That’s Foott Spelled with Two T’s

by Thom Schnellinger

George Foott was a dear friend, incredible western genre painter, amateur historian, antique collector but, to me, more than anything he was a wonderfully dependable kayaker who was always available for a run down the waters of the Arkansas River. Many in the regional boating community will know George, along with Jerry Carpenter and WD Tucker, as being the three guys always available to assist beginner and intermediate boaters. They led many trips through the Numbers, Fractions and Brown’s rapids. They also dug many new boaters out of that water while the “pups” were learning. George was also a reliable and skilled slalom gate judge. During FibArk, he and I often partnered a gate and had a fine time. He’ll be missed on the banks of the river this June.

We hung together a lot. Our goals were boating “all the time” — forty days of summer and well into the winter. We embraced the open waters of winter, punctuating by an annual New Year’s float starting in Salida. Everyone had to roll through the frigid water. One of the New Year’s trips down through Bear Creek rapids began with the thermometer around 45 degrees but, by the time we took out, covered in ice, the temp had dipped below 30. That was enough for George.

He and I spent hundreds of winter hours in the Salida Hot Springs Pool doing countless rolls and perfecting our techniques. When we got bored with that we would play games like rolling without a paddle or passing the paddle over the bottom of the upside-down boat. On Sunday mornings, we would finish with a breakfast at the Patio Pancake and tell tall boating tales. Those stories ranged from past trips to boat design, to boating personalities. George so loved to eat breakfast with us and talk boats. I’m pleased that my last conversation with George this past December turned to those familiar topics. He loved kayaking. (He gutted Skull Rapid Class 3-4 in Utah’s Westwater Canyon, straight on, sort of legendary I understand!)

George and WD were especially supportive and helpful when my son Micah was learning how to kayak. Micah took up the sport in the 6th grade and George was eager to help. It is a tough sport for any father to teach and those guys took Micah under their wing and let him go. Micah is still boating and George never failed to ask about him.

George set his clock to the flows of the river. He embraced the Arkansas. The wonders of the water were always in his thoughts. He lived on the river honing his skills. He was a skilled, fearless and talented boater. I believe he loved the Arkansas Valley and Salida because of their orientation to the river. In Salida you don’t need compass points, you just know where the river is, where it’s going, what the flows are and when it gets big. George enjoyed guessing which valley flash-flooded by the color change of the river. It’s a culture. Those that know it understand.

I will miss George Foott. He was a devout boating friend that I and others counted on for many years. I know that he will not be forgotten.

Thom Schnellinger is the principal at Moffat County High School in Craig, Colorado. He was an art teacher from 1989-2005 at Buena Vista High School. He is also a watercolorist and past president of the Chaffee County Council of the Arts. He served on the first Buena Vista Whitewater Park Committee and was a gate judge for the FibArk Slalom Races. He works hard at boating all the time.

From a Fellow Artist

by Charles Frizzell

I met George about 25 years ago at an art function in Victor. A happy, smiling, energetic man, he and his wife Shirley were in the process of redoing a small building in town, frequently coming up from the Denver area to work on the building and to relax. George was in “mining artifact heaven” in those early days, as the area was littered with mining memorabilia if one knew where to look. I was taken with his black and white pen and ink drawings of that time. With an exquisite attention to detail and fine line work the mining camp came alive under his pen. We occasionally had some time to sit with a beer in the hot high-altitude sun and talk art, old cars, and more art. George was interested in almost everything and every topic filled him with enthusiasm. He was especially interested in the mining history and the human factor of early hard rock mining, as well as being fascinated by the shapes and ingenuity of the early tools. He began painting them with a keen observation of small nuances of metal, wood, and glass, turning those tools of labor into beautifully rendered objects of art.

George was a sensitive and thoughtful man and enjoyed his quiet studio as well as the outdoors and the river. He had a deep reverence for those miners that used the tools he loved to paint, and in this, he was a humanist in the truest sense of the word. His paintings will live on, and will bring understanding and joy to many, now and in the future. We miss you George, but we thank you for the legacy you left for us and for the coming generations.

Charles Frizzell, an internationally recognized and award winning artist, lived and worked in the Cripple Creek/Victor area from 1969 until 1994 when he moved to Salida. He now has his home and studio in Cañon City.A Peek Into the Past

by Wendell E. Wilson

George told me that he was first inspired to create artworks of mining artifacts and scenes after seeing my pen-and-ink drawings in A Collector’s Guide to Antique Miners’ Candlesticks (1984). Thereafter, in the evenings and on weekends, he spent his spare time sketching and painting, and since retiring in 1999 he has been able to devote even more time to his art. He learned how to work with oil paints and how to mix colors from a neighborhood art teacher, and began producing oil paintings in 1990. He also began to incorporate his old mining artifacts (miner’s candlesticks, carbide lamps, tools, blasting cap tins and the like) into his still life paintings.

His illustrations have appeared in a number of books on Colorado history including The Little Book Cliff Railway (1984), Cripple Creek Bonanza (1996), Pikes Peak Gold (2000) and The Great Pikes Peak Gold Rush (2000). His artwork has also been published on notecards and calendars, and he designed a silver medal issued by the American Numismatic Association to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the town of Victor, Colorado where some of the richest gold mines in the state were located. His artworks have won numerous awards and have been displayed in many shows throughout Colorado and Wyoming. He was honored in 2004 to be included in the prestigious Colorado Governor’s Invitational Art Show.

Excerpted with permission from an article in The Mineralogical Record, Volume 40, January-February 2009 by Wendell E. Wilson, Editor-in-Chief & Publisher. He is author or co-author of over 80 major articles and 13 books in mineralogy, including his most important work: The History of Mineral Collecting 1530-1799, plus over 250 column installments.The Mineralogical Record caters primarily to mineral collectors, mineralogists and mineral museum curators, but mining history is also covered, and many of our readers also collect mining artifacts and mining art.

Randy Pruitt

Colorado Central Magazine spoke with George’s stepson, Randy Pruitt, who lives in Denver with his wife and two boys and works as a commercial fly-fishing guide and chef. George married Randy’s mom Shirley in 1972, when Randy was five years old. He shared the following thoughts with us:

I learned an appreciation of the outdoors from George — camping and nature skills, and a great appreciation for the mountains. We did a lot of backpacking in the hills, exploring old ghost towns and artifact hunting. The thing was, I was usually reluctant to tell my schoolmates I had spent my weekend out digging in 100-year-old outhouses!

He was really kind of a hermit in his late 50s until my Mom encouraged him to get out more. He was around 60 when he decided to take up boating. The river became a catalyst for my relationship with him. It gave us something more in common than just my Mom.

George just loved to paddle and had a lot of courage. After one his trips to South America he was offered a job as a river guide but turned it down. He figured he had the best whitewater available just outside his back door in Salida.

George was just a badass.

George, I miss our discussions of Colorado History. I charish the pieces I got from you. We are only stewards of these things.

Your Friend Terry

I own a “Davis Horse Whim” brass tag that is portrayed in one of his paintings. I had to tell someone…hehe.