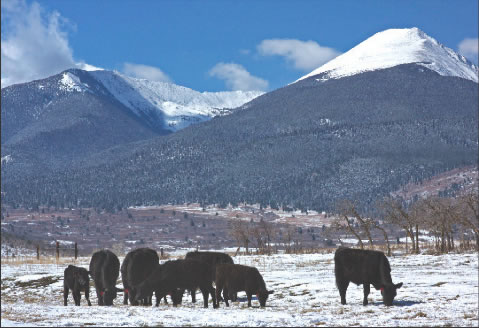

Cotopaxi grass farmers enjoy profitability while preserving land

Story by Susan Bavaria

Photos by Mike Rosso

A small percentage of cattle ranchers have laid down their agricultural arms and made peace with Mother Nature. Instead of inoculating, spraying, inseminating, supplementing, feeding and fighting blizzards to rescue calves born in February, these ranchers opt to coax the land into doing what comes naturally.

For centuries, bison and rangeland had a symbiotic relationship. Wherever bison roamed hooves trampled seeds and churned soil, pushing nutrients from manure down into the ground. The disturbed soil led to increased plant diversity and kept invasive species from gaining a foothold. Weak and defective animals self-culled through disease, hunting and drought.

Today’s grassfarmer attempts to mimic this environment, getting as close to what is natural for a cud-chewing mammal to do as possible. While improvements may have speeded up and increased production, a non-traditional rancher says that has little to do with profitability.

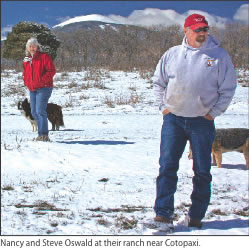

“The sun is free!” says Steve Oswald who with his wife, Nancy, owns the Oswald Cattle Company in Cotopaxi, Colo. Here they raise cattle and goats for meat production in a sustainable way that follows the natural lifecycle of both the animals and the land they graze. It’s an ecosystem that starts with sun.

“It’s how you manage solar energy, water and soil minerals with the least amount of oil and machinery between those raw resources and your finished product that generate wealth,” says Steve. “It’s all about how to build your pasture into a better solar panel.”

Initially, the Oswalds followed a more traditional ranching style. “It was primarily organic except we did use hormones,” Steve says. Then 14 years ago after attending a Ranching for Profit School in Colorado Springs, Colo., they made what Steve calls a “paradigm shift” in operations.

They altered calving time and sold hay equipment, eliminating the work and expense of putting up hay and feeding it during winter months. They made a conscious decision regarding the type of cattle chosen too.

“In American agriculture the trend has been bigger is better,” says Steve. “I looked for an earlier maturing animal because the intramuscular fat (marbling) comes after they reach a mature weight.”

While their primarily Angus cattle may have a smaller frame and lower birth weight (which incidentally lowers stress on both calf and cow), they’re healthier because they land on hard ground during June and July, the optimal grazing time for the moms. (Nursing cows double their caloric intake.) Plus the calves don’t have to endure cold and confinement that can lead to disease. Oswald also holds onto his steers at least two years because it takes longer to reach processing weight on grass. Typical feedlot processing occurs anywhere between 12 and 18 months.

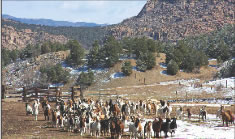

A critical practice of this type of ranching is Management Intensive Grazing which prevents overgrazing and allows grasses to recover. As winter subsides, cattle move to a higher part of the ranch where they move daily to one of 50 different pastures, grazing some once and others several times. Stewardship is key, and grass farmers use several tools to gauge the impact of grazing and moisture.

The Land EKG method of rangeland monitoring measures both improvement and degradation. The Oswalds have established 13 permanent 200 foot sample areas of vegetation called transects. Once a year, they photograph four identical patches along each transect every 50 feet and record variables such as diversity of living organisms, erosion, plant density, amount of bare ground, etc., which is charted on graphs that can be compared to preceding years.

“This gives me proof that the way we ranch actually benefits the land and also helps us manage the business,” says Steve.

For instance, drought has precipitated the sale of 20 steers in April because the land this year won’t sustain keeping them throughout the summer when they would normally bulk up to a finishing weight.

“We try to marry the economical with the ecological,” he says, a theory that prompted them to add a herd of 250 goats to eat the brush and forbs that cows don’t eat.

Operating from a base of 2,700 acres purchased by Nancy’s grandfather and two uncles in 1948, the Oswalds also lease 5,500 acres from the Bureau of Land Management and run cattle part of the year on the neighboring Eagle Peak subdivision.

“Colorado is one state that gives a tax break to homeowners who allow agricultural use on their property,” says Steve.

In the fall, Steve drives his own cattle to a small plant in Elizabeth, Colo., where they are unloaded into a quiet holding pen and given water before processing the following day. They sell everything by word of mouth and advertise less each year.

“Trust is a huge issue with a business like ours,” says Steve. “People want to know who raised it and where it came from. You could say our mission with customers is to reconnect them with the food they eat because there’s such a sterile relationship between food and people.”

While the niche is small, the market for grassfed beef is surging according to the National Sustainable Agriculture Information Services because of new nutritional information about its healthful qualities. Or as philosopher/grassfarmer Joel Salatin states in Michael Pollan’s book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, “The yearning in the human soul to smell a flower, pet a pig and enjoy food with a face has never been stronger.”

Learn more about the Oswald Cattle Company at www.backcountrybeef.com

Susan Bavaria lives in Salida and often finds ways to distract herself from writing.(Editors note: The Oswalds are also finalists for the 2009 Leopold Conservation Award in Colorado. The award is named in honor of world-renowned conservationist Aldo Leopold and is presented annually in seven states to private landowners who practice responsible land stewardship and management.)