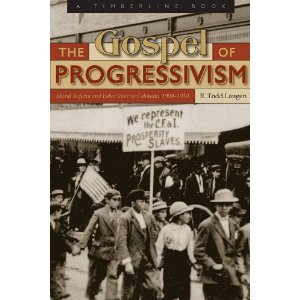

The Gospel of Progressivism – Moral Reform and Labor War in Colorado, 1900-1930

By R. Todd Laugen

University Press of Colorado

ISBN 978-60732-052-4

Reviewed by Virginia McConnell Simmons

Fans of the Old West tend to forget that Colorado burgeoned in scarcely a half century from a mostly wide-open frontier territory to a state replete with land grant settlers, cowboys and cattle barons, homesteaders, railroads, mining booms and busts, industries, labor wars, cities, merchant princes, and, predictably, political parties. In this welter of competing interests, defenders of humanitarian concerns and moral rectitude looked out and saw that their state not only could, but should, be improved. Such reformers called (and often still call) themselves “progressives,” the staunch descendants of agitators for abolition, temperance, and suffrage, who were ready to take on other battles like child welfare, minimum wage, women’s working conditions, and political party corruption.

Dr. R. Todd Laugen’s book focuses on the years of 1900 to 1930, a period when Coloradans from the two major parties demonstrated pervasive corruption on one hand and desire for change on the other. This period found many middle-class Protestants and social reformers like Judge Ben Lindsey pitted against the political machine of Democrat Robert Speer, Republican industrialists like John Osgood and John Rockefeller, their political puppets in state government, radical union leaders, and elite capitalists and matriarchal social arbiters.

Dr. R. Todd Laugen’s book focuses on the years of 1900 to 1930, a period when Coloradans from the two major parties demonstrated pervasive corruption on one hand and desire for change on the other. This period found many middle-class Protestants and social reformers like Judge Ben Lindsey pitted against the political machine of Democrat Robert Speer, Republican industrialists like John Osgood and John Rockefeller, their political puppets in state government, radical union leaders, and elite capitalists and matriarchal social arbiters.

During the period from 1912 to 1920, Progressives coalesced in the Bull Moose Party, gaining political power briefly in the state. During this period, Colorado witnessed some achievements in the direction of honest government and social welfare, but demonstrated some inconsistent progress while war preparedness captured the public’s attention. Outside of Denver during this decade, labor turmoil and the grip of capitalists and industrialists, notably Colorado Fuel and Iron, continued. An exception was Josephine Roche, a social worker who, following a campaign to clean up public amusements in Denver, later took over northern Colorado’s coal industry from her father.

Dr. Laugen describes the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s in Colorado, with its racism among native-born workers who opposed immigrants in the workplace and communities. Preaching moral reform, at times echoing Progressive doctrine misleadingly, the Klan divided labor sufficiently to get Ben Stapleton elected as mayor in 1922 and Clarence Morley as governor in 1924. Author Laugen’s discussion of the Klan’s activities shows Denver and Cañon City being the most active geographically, although the movement was statewide. In the meantime, the Progressives in Colorado declined.

Readers are given interesting information about Billy Adams of Alamosa. After starting as a state representative in the late 1890s, he served continuously as a state senator until he became governor for three terms, from 1927 to 1933. Although he was a Democrat, his ideology, his rural southern Colorado background, and his constituency were conservative, not progressive – like present-day Bluedog Democrats. Like the powerful “Big Ed” Johnson from rural northwestern Colorado, who served as a governor and U.S. senator, Billy Adams opposed New Deal policies, as Dr. Laugen points out.

His book, however, misses an interesting tidbit pertaining to Billy Adams, as well as to his brother Alva, who had also been a Democratic governor: As head of the police department in Denver, another Adams brother was embedded in the corrupt machine that ran Denver’s politics during Boss Spear’s lengthy tenure as mayor, with wide-ranging influence as the center of population in the state.

Readers with a special interest in women’s history may feel that feminists in the West, who had already hung up their aprons, have received inadequate attention from by Dr. Laugen, who indulges, instead, in maunderings about maternalism and male domination in politics.

For the record, this reviewer feels compelled to add that for more than 50 years, beginning soon after their enfranchisement in Colorado, women held the elected office of State Superintendent of Public Instruction, a position that males were willing to concede to women by default. This post “belonged” first to a Republican but soon afterward was contested by female Republican, Democrat and Populist candidates, who proved capable of vigorous campaigning.

By 1912, women were aggressively vying for nomination to other offices in entrenched male political bailiwicks, particularly for election as a University of Colorado regent, Colorado secretary of state, and state senator. After losing a bitter contest for State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Helen Ring Robinson won election two years later as a Democratic state senator. Although Mrs. Robinson emphasized domestic issues, she showed her mettle in other matters, particularly in leading about 1,000 angry women in a sit-in at the office of milquetoast Governor Elias Ammons, forcing President Woodrow Wilson to send federal troops to restore order at the time of the mayhem at Ludlow.

Stephen J. Leonard has provided a useful introduction with the title “The Varieties of Colorado Progressivism.” More than a dozen cartoons from contemporary newspapers illustrate the political temper of the time, and extensive, annotated endnotes provide insight. For unexplained reasons, the price tag for this hardbound, 239-page volume is a whopping $65, so try to find it at a public library.