Article by Allen Best

Wildlife – August 2007 – Colorado Central Magazine

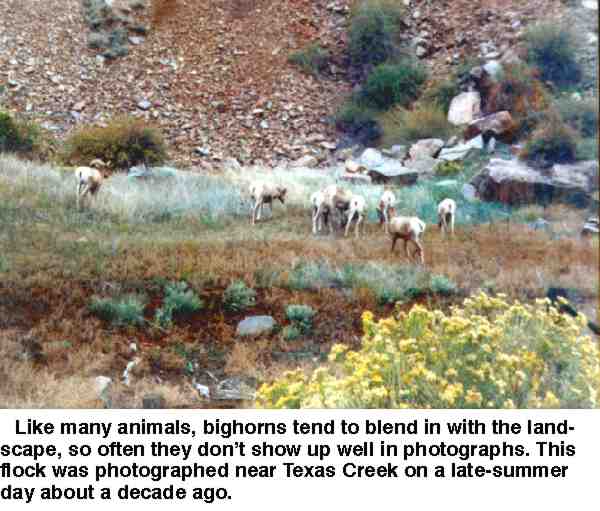

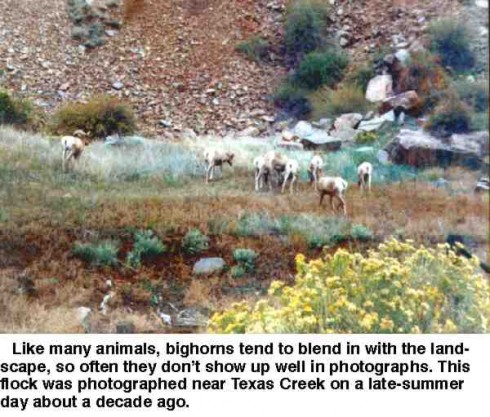

FOR DRIVERS with eyes peeled wide open, the canyon of the Arkansas River between Salida and Cañon City usually has bighorn sheep. They’re not like the sheep along Interstate 70 near Georgetown, which at times graze nearly to pavement’s edge. But the sheep are there, little patches of white against the morning sun, coming down amid the rocks to the river to drink.

An artist could no doubt portray this scene in a painting worthy of a bank lobby. “Sheep Descending to Water,” might be the title. Such a painting could be wonderful art. But the more pressing question is whether the sheep can live with art.

The answer to this question about bighorn sheep could determine whether and how the fabric unfurls in the summer of 2011. What provokes this question, of course, is the fabric canopy called “Over the River” being proposed by Christo and his artist-in-arm, Jean-Claude, which would temporarily convert stretches of the river in an area now designated as Bighorn Sheep Canyon into an art gallery.

BIGHORN SHEEP have long captured the imagination of Coloradans and visitors. The explorer Zebulon Montgomery Pike, in a January 1, 1807, journal entry mentioned coming across a bighorn ram killed by another member of his party near the Royal Gorge.

Forty years later, the traveler George Frederick Ruxton reported the sheep were generally very abundant in all parts of the Rocky Mountains, but particularly in the vicinity of South Park and the Wet Mountains. At least in earlier times, bighorn sheep were more plentiful east of the Continental Divide, because of less snow. Visiting in 1869, naturalist W.H. Brewer remarked that trails were found on all ridges extending into South Park.

Early settlers journaled in a different way. While they named few mountains after deer and none about cattle, the Colorado landscape is littered with several dozen “sheep” mountains. In 1961, the General Assembly named the Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep as the state animal. Given the makeup of the Legislature then, it’s a surprise they didn’t anoint the tail-switching red-and-white Hereford cow.

Like other game animals, the bighorn sheep were nearly eliminated from Colorado during the early years of the state. Market hunters from Leadville and other mining and railroad camps scoured the parks and canyons for elk, deer and bighorn sheep. Denver itself was a major market, and in 1867 a combination of market hunters and sports hunter had killed nearly all of the estimated 4,000 believed to have been in Estes Park and what is now Rocky Mountain National Park.

By 1887 the plundering had become so severe that Colorado legislators banned hunting of bighorn sheep, and didn’t lift the restrictions until 1953. The regulations, when given teeth by creation of a state fish and game department, the precursor of the Division of Wildlife, worked. In 1915, the Boone and Crockett Club estimated the state had 7,230 sheep, a tenfold increase in just two decades.

BUT HUNTING was not the only thing that caused bighorn sheep numbers to decline. Even more powerful, say wildlife biologists, were the diseases spread by domestic bands of sheep, and possibly goats. Both were from Europe and hence introduced bacteria to which the native bighorn sheep had not evolved defenses. The process was similar to that of when the American and Spanish frontiersmen introduced smallpox, measles, and other diseases to the Indians. In the case of the sheep, the cause of death was most often pneumonia.

Even now, sheep remain vulnerable to population swings, particularly when herds become dense. Nor does existence of a population mean it will remain. For example, in the northern Sawatch Range, between Vail and Aspen, native bighorns remained somewhat thick around Mount of the Holy Cross at mid-century. But now, that remnant population has blinked out.

That might have happened in the canyon of the Arkansas River, too. The only sheep remaining by the mid-20th century was a herd of 150 observed in the arid country north of the canyon 20 miles west of Cañon City, between Parkdale and Texas Creek. Another 135 were reported in the Sangre de Cristos, and 300 in the Buffalo Peaks area near Buena Vista, although bighorns were by then absent, or extirpated, from the Wet Mountains.

But after World War II, biologists began to repopulate Colorado’s bighorns, plucking sheep out of herds that had remained strong, such as on the east side of South Park, and inserting them into places where they’d dwindled. Unlike animals like coyotes, bighorn sheep stick to one place. Wildlife biologists say they don’t readily pioneer new habitat on their own.

Twelve transplants have occurred between Salida and Cañon City since about 1980, with the sheep becoming so prominent that former state legislator Ken Chlouber got state highway crews to post signs designating the canyon as “Bighorn Sheep Canyon.”

THE POPULATION of bighorns in the canyon is now stable, says the Colorado Division of Wildlife. Hunters kill eight to ten sheep annually from among the 520 sheep in the region. For the purposes of census work, those sheep can be found far from the river itself, visiting the river only occasionally. Statewide, the population is about 7,200, or about what it was in 1915.

Jack Vayhinger, the terrestrial biologist in this region for the Colorado Division of Wildlife has been driving and walking in the canyon since 1985, and intermittently before that as projects required. “I spent a lot of time in the canyon looking for sheep,” he says. “If you want to spend time and look pretty intently, you can find sheep in the canyon just about any day you go there.”

Bighorn sheep, he says, are well suited to the river and its canyon -and may also be suited as food for mountain lions, which are found in above-average numbers in the area. The sheep owe their survival to their hooves, which give them good purchase among the rocky crags. They can be contained by eight-foot fences, but not if they can find something like a crossbar that will allow them leverage. Their hooves give them what mountaineers call “purchase.”

Another important attribute of sheep is their keen eyesight. They can see well for long distances. As such, they favor the broad shores of the river, where they can see long distances. When wildlife researchers have gone specifically looking for bighorns in the canyon, 90 percent of their observations come within 300 meters of the water’s edge. When they search up the side gullies, they find very little evidence of sheep use. “We surmise that’s due to the fact that most natural springs occur in the bottom of very tight draws, and there’s usually a lot of vegetation, which would conceal predators -mountain lions,” says Vayhinger. “The sheep have learned over time to avoid those water sources, and to instead use the river.”

Water is important. Unlike camels, bighorn must get to water at least daily, sometimes more. Although not all sheep in the canyon rely solely upon the river, says Vayhinger, some do, including those in the area of Parkdale and Texas Creek, the descendants of the sheep that Pike and his men saw in 1806. Particularly important are water sources during spring, when ewes are lactating, and the mothers need fresh water twice daily, or more.

The sheep are, as the saying goes, creatures of habit. Passing trains seemed to bother them very little, nor does automobile and truck traffic. The bighorns have also become reasonably habituated to rafters passing by, unless the boaters do the unexpected and climb onto shore on the north side, where the bighorns are more commonly found.

A more precise understanding of what stresses bighorn sheep was provided by a pilot study. In this study, heart-rate monitors were implanted into three sheep as well as a monitor for a chemical produced in times of stress. The information is transmitted telemetrically to wildlife researchers. Again, the study suggested that habituation is the key, as is the ability to see. These are critters that like to go through life with eyes wide open.

SO HOW WOULD BIGHORN SHEEP see landscape- scale art by Christo? That’s not known with certainty, but Vayhinger suggests the two-week gallery being planned can’t do sheep any good. “We are not sure a sheep will want to come in under a translucent blue curtain to get a drink,” he says. In time, he says, maybe the sheep would gather by the river peacefully.

The key is time. What concerns wildlife biologists is not just the two-week showing, but the two years of preparatory construction and then the post-showing take-down. Too, there are concerns about impacts to both migratory and non-migratory birds. Could, for example, a bald eagle fly blindly into the cables that would be strung across the river?

Just what impact the curtain will have on bighorn sheep is ultimately unknowable in advance. “Our crystal ball is sometimes a little cloudy,” says Vayhinger. He will be the key figure in the Division of Wildlife evaluation, and he expects it will come down to a “professional-guess judgment type of thing.” However, when this conversation took place in mid-June, he had not yet seen the latest 2,029-page proposal submitted by Christo to the Bureau of Land Management. “It’s something we are certainly concerned about.”

The Division of Wildlife also has concerns about impacts to fish — or, to be more precise, to fishermen and women. The agency must consider whether the tent will affect water temperatures and hence the fish and other aquatic life. “I don’t personally have much concern in that area,” says Greg Policky, a DOW aquatic biologist in Salida. The dffect of sedimentations — the result of anchors being set in the hillside and other land-disturbing activities — potentially could be more important.

BUT WHAT CLEARLY CONCERNS Policky is the disruption to fishing, on foot or in rafts, during the slower-water months from early July to September. “The Arkansas is a big destination for a lot of fishermen up and down the Front Range, and if they do come, they’d have to fish elsewhere — if they came at all,” he says. Policky cites a 1995 survey that found nearly 33,000 “fishing days” — one person fishing day — from April through September in Bighorn Sheep Canyon. Most of that use came from July through September. Use since that survey has probably doubled, he says. A better time for Christo’s show, from the perspective of fishing enthusiasts, is during peak rafting season, where there’s more than 1,000 cubic feet per second. Most years, he says, that high water ebbs by early July.

Whatever the Division of Wildlife decides, it’s an advisory opinion. The BLM and the two counties, Frémont and Chaffee, call the shots. “We’re not a permitting agency,” explains Jim Aragon, an area wildlife manager for the Division of Wildlife. “So we normally don’t come out to oppose or support something like this. We basically provide information to the decision-makers who are issuing those permits.”

Allen Best formerly edited newspapers in Kremmling, Winter Park, Vail and Denver, and curreently publishes Mountain Town News.