By Ron Sering

Ken Frye, retired archaeologist with the National Forest Service, gestured to the vast expanse of the San Luis Valley. “We think the Old Spanish Trail went through not far from here,” he said. We were in the La Garita Store, fortifying ourselves with green chili burgers for a tour of rock art sites in the area.

“It’s an ancient trail,” he explained. The Old Spanish Trail was named for the Spanish traders and missionaries who journeyed it between Santa Fe and Los Angeles, but its origins lie centuries beyond that, possibly longer, as a network of foot trails used by Native Americans. “We think people went through here, maybe a thousand years ago.”

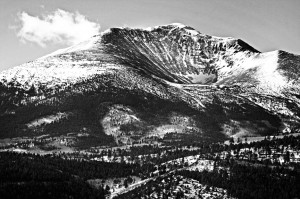

Prior to their removal in 1868, the Utes claimed much of the San Luis Valley as their territory; Blanca Peak, known by the Navajos as Sisnaajini, marks the eastern edge of their ancestral lands. But travelers in the valley date back even farther, to the earliest human presence in North America. “The valley has some of the best Paleolithic sites in North America,” Ken said.

The Clovis People, the top contenders for the first human visitors to the continent, spent time in the valley hunting mastodon and bison antiquus, a bigger and stronger buffalo, leaving behind a handful of their distinctive projectile points. The Folsom People followed them, with verified sites and equally beautiful projectile points in the area around Dunes National Park. “They were the ancestors of the Ancestral Pueblo,” Ken told me, referring to the people known as the Anasazi, a Navajo word meaning ancient enemy.

After lunch, we climbed into high-clearance vehicles for the short drive to the Carnero Creek site, located on private land administered by the Nature Conservancy. Rock formations rose on either side of a grassy meadow bifurcated by Carnero Creek. Sun-splashed rocks, water and tallgrass: perfect snake country, in other words. On one side a shaky footbridge spanned the creek and led to a panel nestled in an alcove beneath a low overhang. “A projectile point I found nearby was about 2,000 years old,” Ken said.

Here, the tiny figures were daubed onto the wall using a reddish paint that has lasted for centuries. “A Hopi elder named Thomas Benyacya came here and identified these images as Hopi,” Ken said. “He said they are flute players.” Careful not to touch the art, he pointed out the figures with a stick. Faint, but clearly humanoid, they hold sticks horizontally aloft, which could easily be flutes held to lips. “I brought a friend, who played his flute right here. You could hear it all over the area. This spot is a natural amphitheater. That’s probably why they put the images here.”

The snakes minded their own business as we crossed the meadow to scale a short wall to the other site, an elaborate display of numerous figures on a flat rock face below a stately rock pillar. “I think that pillar is why they put the art there,” Ken said. Ken pointed out humanoid figures that he called sky dancers hovering over a collage of other images, including deer, and birds that were almost certainly cranes, regular visitors to the valley to this day.

“For a long time, we thought this pictograph was by the Utes, but we brought in a group of Apache Elders, and they identified them as Apache,” he said. “The Apaches and Utes still come to this area. It is very sacred for them.”

Ken pointed out another image lower on the wall, painted with the same color pigment. “This looks like a Celtic knot.” He shook his head, bemused. “I don’t know how that got here.” Celtic knots, as the name implies, are associated with Western European cultures. It was a head-scratcher.

Piecing together the origin and background of sites often involves educated guesswork and reliance on oral history. Ken regularly visits Tribal Elders to learn what had been handed down, but 8,000 square miles and thousands of years can hide a lot of secrets. “These sites are so old. Many of the tribal Elders are dying off, and people just don’t remember,” said Becky Donlan, president of Native American Research and Preservation, Inc., a nonprofit group helping to preserve Native American cultural heritage.

Starting near Saguache and running irregularly to the Rio Grande at the valley’s southern border are a series of rock cairns that could be directional, religious or a combination. “We think many of them were built by Native Americans,” Ken said.

A rock formation on private land near Saguache depicts what could be a geoglyph, a sculpture formed from natural elements, in the image of a serpent. “When I first looked at the property, I asked what it was,” owner Barbara Maat said, “and they told me it was part of a pig farm. But it didn’t enclose anything!” Opinion varies on its true nature. The site has attracted interest from both the Smithsonian and Nazca Lines theorist David Johnson.

The Dry Creek area near Monte Vista is a rich source of petroglyphs, images chipped or pecked into the rock. Author Ron Kessler speculates that Dry Creek was a migratory path for Ute hunting parties. He adds that it was also a popular place for early settlers to quarry stone for building materials, possibly resulting in the loss of additional art.

We had a very serious vandalism problem a few years ago,” Ken said. “A lot of the rock art was being damaged or destroyed with bullet holes or people carving or spray painting their own names over it. I don’t see it as much anymore.” On a couple of occasions, area visitors sometimes brought in human remains to his office. “They’re definitely not supposed to move human remains. It could be a crime scene.”

Archaeological resources are protected from vandalism or theft by a number of state and federal laws, not to mention common decency. Both Ken and Becky offer presentations on resource protection and preservation, available for schools or interested groups.

Ken believes that most of the archaeological resources in the valley have been discovered, “but you never know. Maybe you’ll be the one to make a new discovery.” Later, while we walked a trail in Penitente Canyon, he pointed out a circle of sand beneath a rock overhang, darker than the surrounding area. “That’s an old campfire site.”

How old? “Very old.” So there’s always more out there, if you just go out and look.

Ron Sering explores ancient ruins whenever he can afford the plane fare.