By Mike Rosso

The Ute Indian tribes are the oldest continuous residents of Colorado. The earliest Utes are said to have populated the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains and were hunters and gatherers.

Before the Europeans arrived, the Ute (which means “land of the sun”) were composed of seven bands; the Mouache, Weeminuche, Uintah, Yampa, Parianuc, Tabeguache and Capote. The latter were dwellers of the San Luis Valley and Northern New Mexico. The Tabeguache lived in the Gunnison and Uncompahgre River Valleys. These diverse bands now make up the present day Southern Ute, Ute Mountain Ute and Northern Ute Tribes.

In typical fashion of the so-called Manifest Destiny of the United States, treaties and agreements with the native populations were signed and broken on a regular basis, eventually assigning the Utes to reservations in Southwest Colorado and in Northeastern Utah.

But it can’t be said that U.S. officials were not without some respect for the great chiefs and leaders of these various tribes, for they named several mountains and an entire range, the Sawatch, complete with anglicized spelling, after the Ute word for “blue-green place,” Saguache.

We’d like to delve into the background of the native people who have been immortalized by these grand peaks which reside in their original homelands, and now, our backyards.

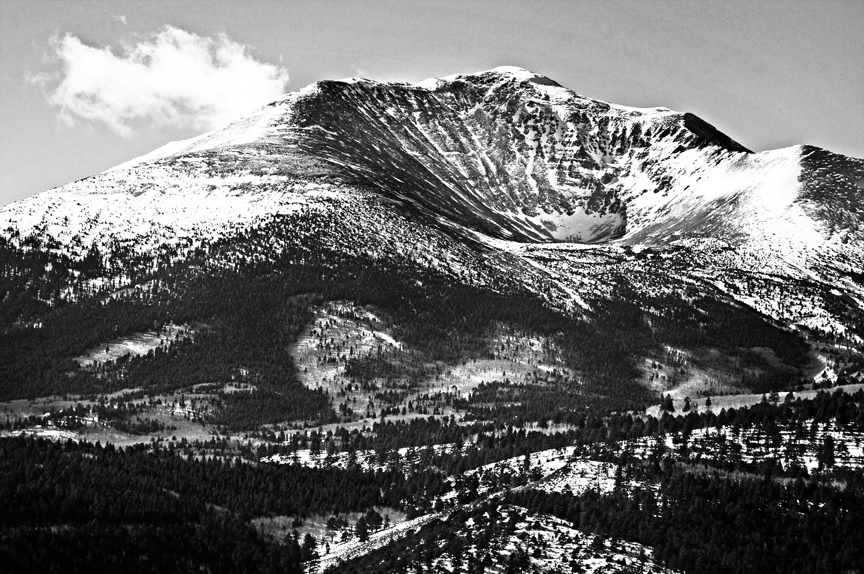

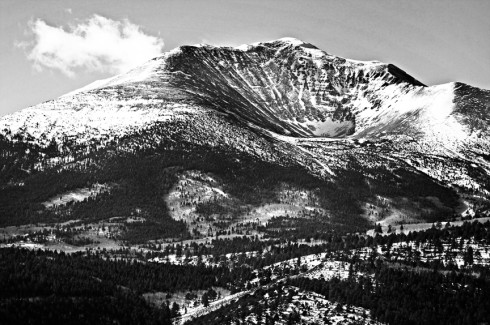

Mount Ouray

At 13,961 feet, Mount Ouray (you-ray) makes up the southern tip of the Sawatch Range and lies about 18 miles southwest of Salida.

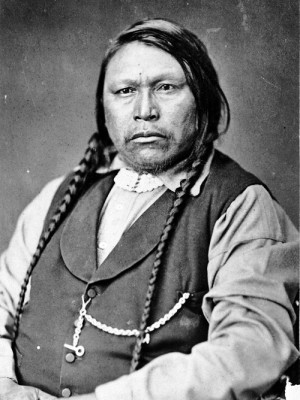

Chief Ouray (the arrow) was a member of the Uncompahgre band of Ute Indians. Ouray was considered to be the chief of all the Utes by the U.S. government, although some tribal members were not crazy about the idea. Ouray was born in Taos, New Mexico in 1833 to a Ute mother and a father who was half Jicarilla Apache. Ouray grew up speaking both English and Spanish, later in life learning Apache and Ute. As a young man, he married a Tabeguache maiden, Black Mare, and fathered a son, Queashegut. While Ouray was on a buffalo hunt north of Denver, the five-year-old son was kidnapped by either the Northern Arapaho or the Sioux.

Ouray first began working with the U.S. government in 1863 with a treaty made by the Tabeguache band at Conejos, Colorado. Ouray was able to translate speeches from Ute to Spanish, which were in turn translated into English. In 1868 he cosigned a treaty giving the Utes 16 million acres of land, mostly in Western Colorado. Then came the gold discoveries in the San Juan Mountains, and the influx of white miners into the area negated any tenancy the Utes had over the land.

Chief Ouray was said to be patient and diplomatic, possessing a strong personality. The Northern Utes, though, felt the U.S. should have chosen one of their own to represent all of the Utes and were slow to accept Ouray. He was even the target of an assassination attempt by his own band. In 1872, five sub-chiefs of the Tabeguache band attacked him at the agency’s blacksmith shop at the Los Piños Agency. Ouray managed to avoid an axe attack by a fellow named Sapawanero, who happened to be the brother of Ouray’s second wife, Chipeta. Gaining an advantage over his opponent, Ouray reached for his knife from his scabbard, only to have it taken by his wife, who wanted to see her brother spared. Witnessing the incident, the other would-be assassins fled the scene.

Ouray was crucial in the prevention of a Ute outbreak that nearly occurred after the Meeker Massacre in 1879. He was granted an annuity of $1,000 per year for his efforts to preserve the peace as long as he remained chief of the Utes. During a visit to Washington, D.C. in 1880, he was called “the most intellectual man I have ever conversed with” by President Rutherford B.Hayes.

Ouray spent much of his time working to solve the issues that arose from the coming of the white man, whom he considered friends and continually kept faith with.

He died on Aug. 24, 1880, on the west bank of the Pine River, after becoming ill on a visit to the Southern Utes. His grave resides in a cemetery southeast of the Southern Ute agency in Ignacio.

Chipeta Mountain

Chipeta, or White Singing Bird, was the second wife of Chief Ouray after Black Mare, who died shortly after the birth of their only son. Born a Kiowa Apache, she was raised by the Utes in what is now Conejos and married Ouray at the age of 16. Her namesake mountain sits northwest of Mount Ouray and is 12,775 feet.

Chipeta (Chip-ee-tah) was a confidant and advisor to her husband, sitting at his side at tribal council meetings, and continued to lead the Ute people after her husband’s death. She often represented the Utes as a delegate to Congress and testified before that body at an inquiry into the Meeker Massacre. Attempting to board a train once at Alamosa, she was nearly lynched by an angry white mob who associated her with the massacre.

Chipeta was known for her masterful beadwork and played guitar and sang in three languages. Although never bearing any of her own, she and Ouray adopted and raised four children. Shortly after her husband’s passing, she and her tribe were forced to move to Utah from Colorado as a result of the Ute Removal Act of 1880.

Chipeta died at the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in 1924 around the age of 80.

Mount Shavano

Mount Shavano (shah-vah-no), 14,231 feet, was named after War Chief Shavano of the Tabeguache Band. It is the 17th highest peak in Colorado and sits south of Tabeguache Peak, named for the Ute band he led.

Shavano (also known as Sha-va-noh or Che-Wa-No) was fourth on a list of 133 Native American signers of the Brunot Treaty in 1874. The treaty had the confederated band of the Ute Nation relinquish lands, mostly in the San Juan Mountains, in exchange for a trust for the natives and allowing the Utes access for hunting on said lands “so long as the game lasts and the Indians are at peace with the white people.” The treaty also offered to erect “proper buildings” and the establishment of an agency on the southern part of the Ute reservation. According to an article by Virginia McConnell Simmons in the June 2005 issue of Colorado Central, Shavano tended to be independent and uncooperative, in contrast to Ouray. Records indicate he was married to Chipeta’s foster sister, Chito, and was a medicine man.

After the violation of Ute territory by prospectors, Shavano went to Washington, D.C. to sign a second treaty. Despite being helpful in rescuing the Meeker family members who were taken captive after the massacre of 1879, he, along with his band, was deported to Utah in 1881 as part of the Ute Removal Act. He died there in 1886 after being shot by the father of a boy who died despite Shavano’s efforts to cure him. The peak was originally given the French spelling “Chavanaux” but was later changed to Shavano.

Mount Antero

At 14,269 feet, Mount Antero is the highest of the “Indian Group” of peaks. Chief Antero was a member of the Uintah band of the Ute.

Also known as Graceful Walker or Chief White Eye because of blindness in one eye, Antero worked to promote peace during the uprisings of the late 1860s and 70s. He was also one of the signers of the Brunot Treaty. He had a fair amount of influence in affairs on the Uintah Reservation due to his cooperation and friendliness with the white man.

Antero was used as a source for ethnological studies by John Wesley Powell and was photographed by Jack Hillers, who accompanied Powell on his Grand Canyon expedition and was also put in charge of taking portraits of Indian leaders when they visited Washington, D.C.

Pahlone Peak

North of Mount Ouray and Chipeta Mountain lies Pahlone Peak at 12,266 feet. Pahlone was originally born to Chief Ouray and Black Mare as Queashegut. He was also called “Paron” (apple) by Ouray or “Cotoan” by his cousins. He was later kidnapped while on a hunting trip near Fort Lupton.

Charles Adams and Otto Mears, Indian agents at the Los Pinos Agency were convinced that if the boy was found and returned to Ouray, he might be more inclined to sign the Brunot Treaty as a sign of gratitude. They began making efforts to find the boy though various Indian agencies. Thus it was learned that Queashegut, renamed Pahlone, had been passed along from the Sioux to the Northern Arapahoes and then to the Southern Arapahoes. Along the way his name was changed again, this time to “Friday,” after a Northern Arapahoe chief.

37 Indians were rounded up in the pursuit of Pahlone, but fourteen escaped, including Friday. He was then found in Indian Territory and brought in but refused to acknowledge any relationship to Ouray or to the Ute Tribes, whom he claimed to despise. But those Utes who met him remembered him as Cotoan, whom they had played with as children. Pahlone was brought to meet Ouray, and witnesses became convinced they were father and son. Pahlone then agreed to go to Colorado but died en route after bidding goodbye to his friends in the Arapahoe Tribe.

Special thanks to Virginia McConnell Simmons and the late Ed Quillen for their research on this topic found in the Colorado Central Magazine archives. Historical materials were also found in The Southern Utes, A Tribal History, published by the Southern Ute Tribe.