Review by Steve Voynick

Local Lore -March 2006 -Colorado Central Magazine

A Thread of Gold

by R. Reed Johnson

Published in 2005 by Western Reflections

ISBN 1-932-73812-6

For a first-time literary effort, R. Reed Johnson took on a daunting task writing a 470-page historical novel with a host of characters and complex time transitions. And for the most part, he pulls it off rather well.

A Thread of Gold covers 150 years of Colorado history, focusing on the 1779 de Anza expedition, the South Park goldfields during the Civil War years, and a Depression-era farm in Littleton. As the title implies, the thread that ties it all together is the search for a gold bonanza.

Johnson begins his tale with two young scouts, the brothers Juan and Pedro Vasquez, who are accompanying Governor Juan Bautista de Anza’s force of 800 Spanish soldiers and friendly Indians on their trek from Santa Fé into what is now Colorado. Their mission is to track down a band of troublesome Comanches led by Chief Cuerno Verde (Green Horn). Johnson follows Anza’s journal faithfully, taking the reader into the San Luis Valley, over Poncha Pass, across South Park, and onto the Plains near present-day Pueblo where Cuerno Verde is killed.

Along the way, the Vasquez brothers meet up with Silas Smith, a lone American trapper who has discovered a rich gold deposit in the Tarryall Mountains. Smith’s character seems based upon James Purcell, a real-life American adventurer who found gold in South Park in 1803 before taking up residency in Santa Fé. Since Smith never intends to return to the site, he reveals its location to Juan and Pedro Vasquez. The brothers head for the Tarryalls and find the bonanza, setting the stage for the remainder of the tale. But more about Part 1 later.

Part 2 takes the reader to the Shadycroft Farm in Littleton during the Depression. The main character here is 11-year-old Robby Johnson who, as the preface reveals, is the author himself. Now that Johnson is drawing on firsthand experience, the quality of his writing improves markedly. The plot also becomes quite engaging as a local character, the eccentric Crazy Sam Baker, is shot in a mysterious confrontation and takes refuge at Shadycroft. During his recuperation, Crazy Sam befriends Robby, then shows him an old journal from the 1860s, purportedly written by his friend John Reynolds.

The author smoothly turns Robby’s reading of the journal into the narration for Part 3, where we learn that John Reynolds is the younger brother of the notorious Texas brigand Jim Reynolds who, under questionable pretenses of securing gold for the Confederacy, did indeed wreak havoc across South Park in 1864. Johnson’s thread surfaces when the Reynolds brothers acquire a map showing the site of a gold mine made some 80 years earlier by, you guessed it, the Vasquez brothers. The ensuing search for the gold is so deftly woven into the Reynolds story that it becomes difficult to separate history from fiction. Johnson spices his tale with mentions of such historical figures as John Chivington, H. A. W. Tabor, Father John Dyer, and Silver Heels, names known to anyone familiar with Colorado history.

Flashing ahead to the 1930s again, Crazy Sam, together with Robby and his older brother J. J., explore the Tarryall Mountains, find the gold, thwart the villains, and thus save Shadycroft Farm from foreclosure during the darkest days of the Depression.

The problems with this book are concentrated in Part 1, which is thankfully short. I sensed that the author wrote this part almost as an afterthought to extend the historical span of the book and impart an added measure of credibility to the gold bonanza. The dialogue between Juan and Pedro Vasquez is stilted, sometimes sounding more like a conversation between two stockbrokers on a camping trip than between two young scouts during the late Spanish colonial period.

As an example, Pedro tells Juan, “… Besides that, I can carry some more in my backpack.” But no one accompanying the de Anza expedition would have said that, because the contemporary term “backpack” didn’t enter the language until the 20th century.

The book has been proofread well except, again, for Part 1. The Comanche chief Cuerno Verde suddenly and inexplicably becomes Querno Verde, with the spellings alternating regularly, even in consecutive sentences.

Johnson’s history is usually, but not always, accurate. After doing away with C(Q)uerno Verde in September 1779, “Anza … ordered his army to begin the march back to their homes in the San Luis Valley and Santa Fé.” Apart from the irritating point that “their” does not relate grammatically to “army,” there would be no Hispanic homes in the San Luis Valley for decades to come.

Furthermore, the plot in Part 1 is implausible. It is unlikely that the trapper Silas Smith, who has spent a year looking for beaver, would have mining equipment such as picks, shovels, gold pans, rope, and blasting powder, but he passes all of that on to the Vasquez brothers. Because the brothers need a mere four days to build a windlass and an arrastra to grind their hardrock ore, and just eight more days to amass a large quantity of gold, I suspect that the author has little familiarity with the difficulties of mining. And Johnson’s depictions of cougar and grizzly attacks, along with his descriptions of an October avalanche, compromise the sense of realism needed to make a historical novel ring true.

R. Reed Johnson was born on Shadycroft Farm in 1921 and is a former Denver pediatrician. Upon his retirement in 1989, he began writing his autobiography, but soon became bored by the humdrum happenings of his own life (although turning a Depression-era, farm childhood into a long, successful career as a medical doctor is not my idea of humdrum ). So Johnson changed direction and reworked his budding autobiography into a historical novel, the researching and writing of which took more than a decade. His autobiographical portions are readily apparent in his fine character development of Robby, his 11-year-old alter ego.

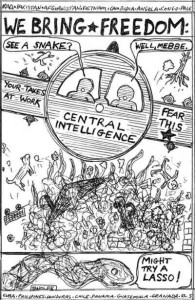

The book includes a few dozen historical photographs and excellent pen-and-ink drawings. Its brief, final section is titled Fact or Fiction? It’s a valuable addition in which Johnson sets the record straight on exactly where history becomes fiction in A Thread of Gold.

Most of this book is quite well-written. While a few aspects of the plot are predictable, Johnson more than compensates by introducing some fine elements of suspense and surprise. And his historical impressions of South Park in the 1860s and of Littleton during the Depression years are first-rate. All in all, A Thread of Gold is a good read, especially for anyone with a background in Colorado history –but only if you can get through Part 1.