by Sterling R. Quinton

On the outskirts of a quiet Colorado town lies a new goat dairy which, despite the steep industrial odds set against it, is making an impressive stand upon some old-time principles.

At the center of that dairy is its founder, Dawn Jump, who embodies the quintessential blend of rugged mountain individualist and collegially articulate woman, calling to mind Isabella Bird and her 1873 collection of letters, A Lady’s life in the Rocky Mountains. The comparison is all the more compelling because Jump’s Colorado lineage harks back to 1892. Her family homesteaded a forty-acre ranch in Calhan, Colorado.

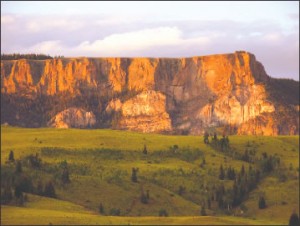

Today, she and her family, with the help of a modest but committed staff, are stewarding agriculture in the upper Arkansas Valley toward a future of sustainability. Her business, The Jumpin’ Good Goat Dairy, is located three miles north of Buena Vista, at the foot of some of the most picturesque peaks ever thrust from terra firma.

The dairy, post kidding (the term for the birthing of baby goats), will milk a hundred goats a day, and is situated on forty-two acres of slanting pastures. The barn, dairy, country store, and corrals were still in a state of construction during a visit in mid-March, but Jump expected the dairy to be ready for public participation in time for its grand opening and celebration on March 20 and 28.

She has her work cut out for her. Besides the often exhausting logistical and clerical aspects of a small business, Jump is also a primary goat milker. At maximum production, when all the does are producing their capacity, Jump expects to be able to create in excess of 100,000 pounds of goat-based product annually.

Jump moved back to Colorado, in part, because the damp climate of Washington was hard on her animals’ hooves. The goat, a small ruminant, originated in drier climes and thrives in this region’s semi-arid deserts. The lush geography of Washington, while not great for the herd, allowed Jump to experiment with washed-rind cheeses. Washed-rinds, such as Livarot or triple crème, tend to be softer cheeses which are regularly splashed during the aging process with beers, brines or other such liquids to stimulate a leathery bacterial growth.

Colorado demands a different kind of cheese production. This means Jump’s dairy will specialize in firm cheeses such as cave-aged Jack, Cheddar, and Gouda: a slightly sweeter cheese. They’ll also carry less common variations like washed-rind Telagio and Feta. The aging process will transpire in the pine-lined subterranean caves Jump herself designed. In addition to the cheese and milk, the dairy hopes to eventually offer an assortment of goat-milk ice creams blending vanilla with fruits, including apricot and peach, procured in the Valley and along the Western Slope.

The dairy’s does alone are not enough to generate all the milk needed for the fifty tons of product she’ll produce. Jump says she’s also partnering with the State of Colorado and proud to be importing milk from Colorado Correctional Industries (CCI).

“That’s part of the Cañon City prison operation,” she said. “CCI is an entity that involves a 1500 head goat dairy. It’s an absolutely fabulous program down there in Cañon City and I’m really proud that we’re a partner with them and able to use them as a source to bring imported (goat) milk here.”

Jump hopes to partner with more local dairy producers in the future. Of course, the more diverse her import sources, the more difficult it can be to monitor the quality of the final product. Not to worry, she’s already considered that angle.

“I’m very proud to say that I have a state-of-the-art cheese room and a grade-A milk processing facility rated to state standards. I’m also proud to say that I have a very in-depth quality-control program that exceeds state standards because I like to know what our milk consists of at any given time,” she said. “I think it is a great path to follow the origin of milk from the beginning to the end product.”

Fervent as her beliefS in stringent quality standards are, they’re overshadowed by an even deeper devotion to the impact her business will have on the local community and foodshed. She makes sustainability an integral part of her work. “As we live our lives today, each and everyday, for myself and my generation, as well as our children and their generation, the ability to achieve sustainable farming is not an option but a must,” she said. “Each one of us must be a part of sustainability.”

One way Jump achieves this vision of sustainability is in the design of the dairy. While she admits to using diesel-based tractors and coal-driven electricity, she says that fundamentally the dairy is successful because of elbow grease and smart design. “For instance, the caves that I designed, they’re naturally ventilated. They’re built into the ground. [The design] takes the rocks that are so abundant in the Arkansas Valley and puts them to good use. 3,700 wheels of cheese can be stored in those caves energy free. Energy free. It’s done by the coolness of the earth. That, to me, is significant. That’s a contribution.”

In addition to placing a premium on energy efficiency and on manual labor, Jump is also working with experts in the field of Holistic Management to ensure that her forty-two acre ranch sustains not only the needs of her animals, but also improves the health of the land. She is working with Natural Resource Conservation Services out of Salida to develop smart water plans in conjunction with rotational grazing designs. This care for the process culminates in what she calls Terroir: a combination of “the flavor of the Earth,” and the quality engendered by incorporating “old-world farmstead traditions” in order to create a truly regional product.

Unfortunately, a commitment to community and tradition isn’t always easy. The hardest part of being principled? The cost. “The amount of money that it takes to do what I’m doing,” she said, “is substantial. The amount of money it takes to do what I am doing and do it in favor of the Earth is more substantial. It’s constant,” Jump says. “You always have to step up to it.”

That cost, of course, is inherent to the nature of a small, locally-based business competing with the well-funded and subsidized goliaths of the industrial farming system. Many times, the exorbitant cost is enough to unseat a person’s drive to achieve their passions. Hearing the words of this ardent and astute businesswoman, however, gives a sense of Jump’s commitment. It also begs the question, “What is your inspiration?”

Jump gets that from seeing the effects of her work. Of the catalyst for her hope, she said, “I can feed people sustainably. I can nourish people in mind, body and spirit. When I bring people to this dairy and they are able to tour and see the babies, feed the little kids and be involved in holding these creatures, and then they’re able to come into the milk parlor, and their children are actually able to milk a goat and see with their eyes where that milk travels and how that process takes place. That’s nourishment on levels of all types. All of those things give me hope.”

Sterling R. Quinton, born and raised in a state of utter confusion, freelances from somewhere in Colorado. Contact him at writesterling@live.com