19th-century sojourner Samuel Bowles wrote in 1869: “This (South Park) is the more beautiful of the parks…It offers a remarkable combination of the beauties of the Plains and those of the Mountains. They mingle and mix in charming association.” (Photo by author)

Colorado is chock full of legends and lore, from mysterious mining tales to haunted hotels. Some of the most intriguing stories include Wild West characters and buried treasure. Two of southern Colorado’s most famous legends involve the Espinosa brothers’ murderous swath through Park County in 1863 and the Reynolds Gang’s destructive path and alleged hidden gold in 1864. Even though both bands of brothers rode during Colorado’s territorial years nearly 160 years ago, their stories still hold a modern-day fascination.

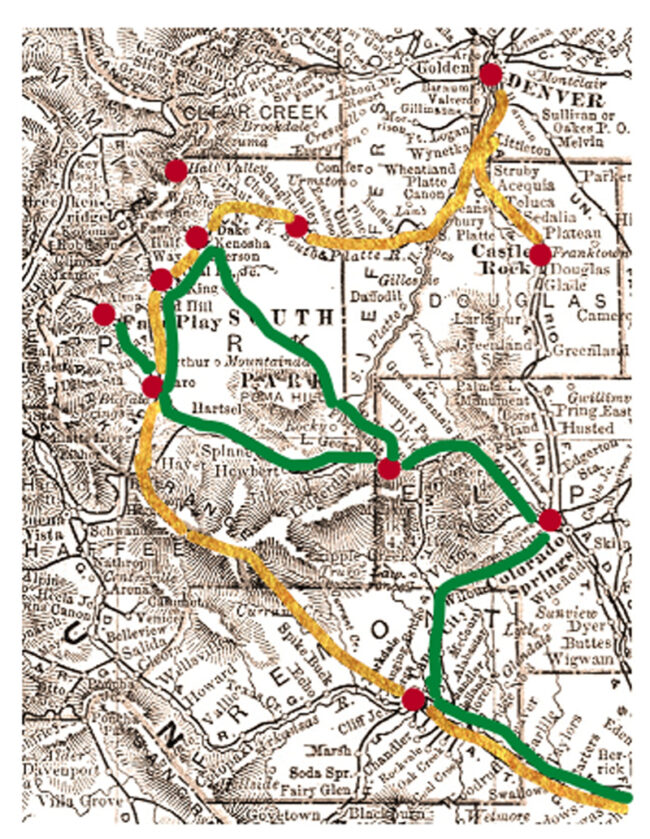

As with many legends, the truth can quickly becomes distorted, which is especially true with these stories, making it nearly impossible to separate fact from fantasy. For example, there are four different versions of where the Reynolds Gang buried their gold, and recent research has shed new light on some of the Espinosa myths. Both groups of brothers allegedly traveled similar, if not sometimes identical, routes through Park County and the South Park Basin within a year of each other.

The region’s stunning scenery has long been the subject of glowing pastoral accounts by such famous writers as Helen Hunt Jackson and Walt Whitman. Originally home to the Ute, Arapaho, Comanche and Kiowa, South Park was later frequented by trappers and explorers. The 1859 Pikes Peak Gold Rush brought in a surge of gold seekers who promptly established mountain mining camps along with ranches to support the new mineral industry.

Let’s mount up and ride along this historic outlaw trail, highlighting the brothers’ paths, why they chose them, their presumed deeds along the way, the fear they instilled and their ultimate demise.

The early 1860s were a tumultuous time for the United States and the Colorado Territory due to the Civil War, the gold-mining frenzy and conflicts between Anglo-Americans and other cultural groups, especially indigenous peoples and Hispanos. The influx of post-war Confederates seems to have caused considerable trouble as their activities affected U.S. soldiers, the Territorial government and residents alike.

The Espinosa and Reynolds forays into Park County and beyond were motivated by very different circumstances. For Hispano brothers Felipe de Nerio and José Vivián Espinosa, the reasons presumably included heightened resentment against Anglo settlers and government officials because the family lost their land and home.

“Fabricated Rumors”

Readers, historians and researchers must understand that there were many uncomfortable events taking place in Conejos during the early period of Colorado Territory; specifically, 1861-63. I believe the Espinosa Brothers were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Perhaps their troubles began at California Gulch near Leadville, as these miners were the ones who first tracked them down. Many miners arriving into southern Colorado fled conscription in the South but retained Confederate sympathies. They disliked Ute and Hispanos near their diggings. They, and others, felt Hispanos were not U.S. citizens; when in fact, the Hispanos had been U.S. citizens longer than most Anglo soldiers and miners coming into southern Colorado. Military accounts tell us these Confederates were making trouble for the Utes and causing additional problems in and around the area. The air was rife with suspicion, blame, mistaken identity and alcohol. The rumors and stories about the Espinosas were simply fabricated due to biases and prejudice against Hispanos.

— Virginia Sánchez, author of Pleas and Petitions: Hispano Culture and Legislative Conflict in Territorial Colorado

After the Mexican-American War in northern New Mexico, the Espinosa family moved north to Colorado’s Conejos County. Times were hard, and the brothers were reportedly seen robbing a freight wagon in a last-ditch effort to support their families. Cavalry Lieutenant Nicholas Hodt tried to peacefully corral the two by tricking them into joining the military, but when they refused, Hodt ordered their home burned. Other theories for their actions range from the religious to the criminal.

New interpretations of the Espinosa legend have recently been proposed by Denver-based scholar Virginia Sánchez, who notes that an accurate description of the brothers was never issued; the laws were not translated into Spanish for those New Mexicans who were in the Colorado Territory; and Hispanos were typically regarded with suspicion in the mining communities.

The Espinosa brothers were accused of committing the following murders and some postmortem mutilations: Franklin W. Bruce on Hardscrabble Creek, March 16, and Henry Harkins near present-day Fort Carson, March 18. Traveling north to Colorado City, now on Colorado Springs’ west side, they supposedly headed up Ute Pass along a historic Ute trail, entering South Park at Wilkerson Pass. The brothers were then accused of the following killings and some mutilations: rancher John Addleman south of Wilkerson Pass, March 31; Jacob Binkley and Abraham Shoup near the east base of Kenosha Pass, April 8; Bill Carter near Fairplay, April 25, and Messrs. Lehman and Vinton (aka Segga or Seyga) on Red Hill Pass, April 26. Carter’s murder was significant in that a passerby saw the ambushers, describing them as “men blackened” according to Father Dyer in his autobiography, “The Snowshoe Itinerant,” but this description fits men of many different nationalities and did not necessarily apply just to the Espinosas.

Next, their route becomes confusing with its zigzags and backtracking, raising questions as to whether it was just the Espinosas’ route or if other marauders were active in the area. Their supposed trail added up to a hefty distance of 160 miles via today’s roadways. Being on foot or horseback would have greatly increased the time needed to travel such distances.

As to be expected, news of a rampage struck fear in the hearts of Park County residents. The Rocky Mountain News Weekly of May 16, 1863, printed a letter written by a prominent local miner and lawyer: “A vague, undefined sensation of dread and fear restrains the free actions of persons who for three or four years have been accustomed to traverse the Park and the mountains without a shadow of doubt as to their safety.”

A posse tracked the brothers southward to a gulch north of Cañon City where Vivián was shot and killed on April 27, 1863. His body was either buried or left exposed to rot. Felipe escaped and returned to southern Colorado, where he remained in hiding until tracked and killed by frontiersman Thomas Tobin and companions on Sept. 10, 1863. Felipe’s nephew, possibly 14-year-old José Vincente Espinosa, who is said to have accompanied him, was also shot and killed. Tobin then beheaded both men and returned to Fort Garland, where he dumped out the heads in front of Commander Colonel Tappan as proof of his conquest.

The Reynolds Gang was ostensibly motivated by the Confederate cause in Colorado Territory, but this may have been secondary to their personal desires for goods and gold. The Reynoldses traveled north from Texas, entering Colorado at the southeastern point via the Santa Fe Trail then passed through Cañon City. Traversing Currant Creek Pass around July 20, 1864, now Colorado Highway 9, they headed into South Park, staying overnight at Adolphe and Marie Guiraud’s ranch, now home to the Rocky Mountain Land Library.

The next day, the gang rode north to Daniel McLaughlin’s ranch and stagestop near present-day Como, where they awaited the Buckskin Joe stagecoach. When it arrived, the gang promptly robbed driver Absalom Williamson and stage owner Billy McClellan of cash, a watch and a gun. The following also transpired according to cohort Thomas Holliman, who was later captured and forced to describe the gang’s pillaging: “Jim and another one of our boys took out the Express trunk, got the key from one of the men, opened it, and took the money; there was three or four thousand dollars in gold dust. … Jim said he wanted to do the U.S. all the damage he could and ordered me to cut up the coach wagon. I got an axe and one of the others took the axe and chopped the wheels to pieces.”

Next, the gang stopped in the foothills in or near Platte Canyon, unaware that they were right smack in the middle of several posses. A small one, including Salt Works Ranch owner Charles L. Hall, was riding ahead to warn settlers of the gang’s path toward Denver. Another posse, headed by Breckenridge miner Jack Sparks, discovered the desperados’ encampment July 30, 1864, and snuck up on the gang. Firing into the group, Sparks’ posse killed and subsequently beheaded Private Owen Singletary and wounded Jim Reynolds with a shot to the arm.

Just before being ambushed, Reynolds allegedly hid most of the outlaws’ gold and currency. Four different versions of the narrative claim the treasure’s value ranged anywhere from $2,000 to $100,000. Purported cache locations include Hall Valley along today’s Park County Road 60, according to an Oct. 11, 1892, report in the Rocky Mountain News. “Trail of the Broken Dagger,” an article in the August 1964 issue of True West Magazine, mentions Handcart Gulch, aka Webster Pass, along U.S. Forest Service Road 12 as a possible location of the stolen goods. A chapter in The Rocky Mountain Empire entitled “The Mystery of Handcart Creek” also identifies Handcart Gulch as the location of the treasure.

An August 2000 article in Colorado Heritage Magazine, “No Time for a Trial,” identifies Geneva Gulch, aka Guanella Pass, now traversed by Park County Road 62, as a possible location. Finally, according to the book, Hands Up! Or Thirty-Five Years of Detective Life in the Mountains and on the Plains by Dave Cook, includes a map that marks the treasure location below Rosalie Peak south of today’s Harris Park community near the headwaters of Deer Creek. This includes a map with the treasure location marked. Frank Hall’s History of Colorado also points to the likelihood that the treasure was stashed at a Deer Creek location.

Jim Reynolds and his cohorts were subsequently captured near Cañon City on Aug. 13, 1864, by Lt. George L. Shoup, whose brother was killed the previous year near Kenosha Pass. John Reynolds and another man, Addison Stowe, escaped and headed south. The remaining prisoners were transported to Denver for trial; although, the notorious Col. John M. Chivington seized the men from a federal marshal. On Sept. 1, 1864, Chivington sent the prisoners, shackled together, to Fort Lyon with Captain Theodore Cree and soldiers with the 3rd Colorado Cavalry.

Near Franktown, at the Russellville settlement, the unit separated, leaving only a small group to deal with the men. The group was headed by Sgt. Allen Shaw and Absalom Williamson, the driver of the Buckskin Joe stage who was previously robbed by the gang. Several versions claim that Shaw ordered his men to fire on the shackled prisoners and that Williamson immediately shot and killed Jim Reynolds. The other men refused; whereupon, Shaw fired once and Williamson finished the job. Several months later, a well-known Colorado frontiersman, “Uncle Dick” Wooten, said he found the men’s bodies, still shackled to a tree. Chivington went on to lead the atrocious Sand Creek Massacre only four months later. According to the Colorado Encyclopedia, the Reynolds gang’s convictions were overturned in February of 1865.

Our ride-along shows the deep-rooted legends these two bands of brothers left in their trail, despite some factual evidence to the contrary, and the Reynolds Gang’s posthumous pardons are rarely mentioned. The Espinosas’ story contains numerous myths, as evidenced by Virginia Sanchez’ research. It is possible that other, more discreet brigands, were riding during this time, yet the Bloody Espinosas moniker still sticks with us.

Wild West tales can provide many hours of entertainment (see the full list of resources below). When doing your own research, however, keep in mind that there are numerous versions with many sensationalized accounts. Outlaws are part of the romanticized myth of the West, and the Espinosas and Reynolds Gang will continue to ride on in history — hopefully with a more grounded reputation.

Christie Wright is a Colorado author and the former president of the Park County Local History Archives, where she volunteered for 8 years. After retiring from her job as a probation officer, she turned her interest to writing about Colorado’s historic “bad guys.” Christie is a member of Women Writing the West and Western Writers of America.

SOURCES USED

BOOKS

“A Brief History of Fairplay” by Linda Bjorklund, History Press (2013).

https://www.arcadiapublishing.com/Products/9781609499556

“A Confederate In The Colorado Gold Fields” by Daniel E. Conner, University of Oklahoma Press, 1970.

“A Wild West History of Frontier Colorado” by Jolie Anderson Gallagher, 2011.

“Bandit Years – A Gathering of Wolves” by Mark Dugan, Sunstone Press, 2007

http://sunstonepress.com/cgi-bin/bookview.cgi?_recordnum=14

“Bayou Salado” by Virginia McConnell Simmons, University of Colorado Press, 2002.

https://upcolorado.com/university-press-of-colorado/item/1728-bayou-salado

“Colorado Treasure Tales” by W.C. Jameson, Caxton Press, 2001

https://www.caxtonpress.com/coloradotreasuretales.aspx

“Colorado Lost Gold Mines and Buried Treasure” by Caroline Bancroft, Johnson Books, 1976.

“Colorado Myths and Legends: The True Stories behind History’s Mysteries” (Legends of the West) by Jan Murphy, 2016.

“Colorado Gunsmoke: True Stories of Outlaws & Lawmen on the Colorado Frontier” by Kenneth Jessen, 1995. https://www.facebook.com/PruettPublishing/

“Forgotten Tales of Colorado” by Stephanie Waters, the History Press, 2013.https://www.arcadiapublishing.com/Products/9781609498863

“Hands Up! Or Thirty-Five Years of Detective Life in the Mountains and on the Plains, A Condensed Criminal History of the Far West” by Dave Cook, The W.F. Robinson Printing Company, 1897.

“History of Colorado, Volume 1” edited by Wilbur Fiske Stone, S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1918.

“History of Denver: With Outlines of the Earlier History of the Rocky Mountain Country” edited by Jerome Constant Smiley, The Times-Sun Publishing Company 1901.

“Lost Bonanza: Tales of the Legendary Lost Mines of the American West” by Harry Sinclair Drago, Dodd-Mead Publishing (now defunct), 1966.

“Man-Hunters of the Old West” by Robert K. DeArment, 2017.

“Mysteries and Legends of Colorado: True Stories of the Unsolved and Unexplained”(Myths and Mysteries Series) by Jan Elizabeth Murphy, TwoDot Books, 2007.

“Outlaw Tales of Colorado” by Jan Murphy, TwoDot Books, 2012.

http://twodotbooks.com/books/search/outlaw%20tales%20of%20colorado

“Pioneers of the Colorado Parks” by Richard Barth, 1997.

https://www.caxtonpress.com/search.aspx?find=pioneers+of+the+colorado+parks

“Pleas and Petitions: Hispano Culture and Legislative Conflict in Territorial Colorado

by Virginia Sánchez, 2020.

https://upcolorado.com/university-press-of-colorado/item/3672-pleas-and-petitions

“Raids by Reynolds, 1956 Brand Book, published by the Denver Posse of Westerners, by Kenneth Englert, 1956.

“Rebels in the Rockies” by Walter Pittman, McFarland Publishing (2014).

“Reynolds Gang: Confederate Outlaws With A Cause” by Ben Benoit, The CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012 (novel).

“Season of Terror: The Espinosas in Central Colorado, March-October 1863” by Charles F. Price, University of Colorado Press, 2013.

https://upcolorado.com/university-press-of-colorado/item/1984-season-of-terror

“Spirits of the Border: The History and Mystery of Colorado” Omega Press, 2007.

(no working website).

“The First Hundred Years” by Robert L. Perkins, Doubleday & Co,1959.

“The Rocky Mountain Empire” and the chapter entitled, “The Mystery of Handcart Creek.”

“The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: History of Nevada, Colorado, and Wyoming”

by Hubert Howe Bancroft 1540-1888 The History Company, Publishers (San Francisco) 1890.

“Tom Tobin: Frontiersman” by James E Perkins, Herodotus Press, 1999.

(book not listed on their website).

“Tom Tobin and the Bloody Espinosas The story of America’s first serial killers and the man who stopped them” by Bob Scott, 2004.

“The Vendetta of Felipe Espinosa” by Adam James Jones, (Thorndike Press Large Print), 2015. https://www.facebook.com/ThorndikePress

INTERNET LINKS (URLs)

Denver Public Library

https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/reynolds-gang-colorado-confederates-and-their-buried-treasure

LIFE…DEATH…IRON: Ghost Towns, Road Trips, and Obscure History

by Jay Eberle

The Colorado Encyclopedia: The Espinosa Brothers

The Colorado Encyclopedia: Reynolds Gang

https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/reynolds-gang

The Colorado Prospector

http://www.coloradoprospector.com/forums/index.php?showtopic=2262

The Royal Gorge Regional Museum & History Center Blog

Now & Then: The Espinosa Brothers APRIL 28, 2020, by BRANDON MARES

MAGAZINES

“Colorado Heritage Magazine: No Time for a Trial – The Abrupt Fate of the Reynolds Gang” by Ariana Harner, August 2000.

“Colorado Magazine: The Capture of the Espinosas” by Tom Tobin, 1932

“Colorado Magazine: “Tom Tobin” by Edgar L. Hewett, 1946.

“Colorado Magazine: Confederate Guerillas in Southern Colorado” by Morris F. Taylor, 1969. https://www.historycolorado.org/sites/default/files/media/document/2018/ColoradoMagazine_v46n4_Fall1969.pdf

“True West Magazine: The Trail of the Broken Dagger” by Vernon L. Crow, August 1964.

“Empire Magazine, A Supplement to the Denver Post: Legend of the Lost Reynolds Gold,” October 19, 1975, p.10.

NEWSPAPERS

Colorado Historic Newspapers

https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/

PODCASTS

“Beyond the Valley of a Doubt: Lost Highways: Dispatches from the Shadows of the Rocky Mountains” by History Colorado, March 7, 2022.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/6qfmL07haukZMdvlynYyXM?si=x6gRyHfOQCCE62wPdo5cNQ

SCOLARLY WORKS

“Re-Examining the Mob Violence Against the Espinosas in South Territorial Colorado, 1862-1863” by Virginia Sanchez, 2017.

https://www.academia.edu/34625684/Re_Examining_the_Mob_Violence_against_the

“The Outlaw: A Distinctive American Folktype” by Richard E. Meyer

Journal of the Folklore Institute, Vol. 17, No. 2/3, May – Dec., 1980

https://www.jstor.org/stable/i291288