By Charles F. Price

On July 17, 1882, nine days after a visit to Salida – described in the April and May 2009 issues of Colorado Central – John H. (“Doc”) Holliday pulled into the town’s division yards on a DR&G train from Pueblo, headed for the silver camp of Leadville. This time he didn’t get off.

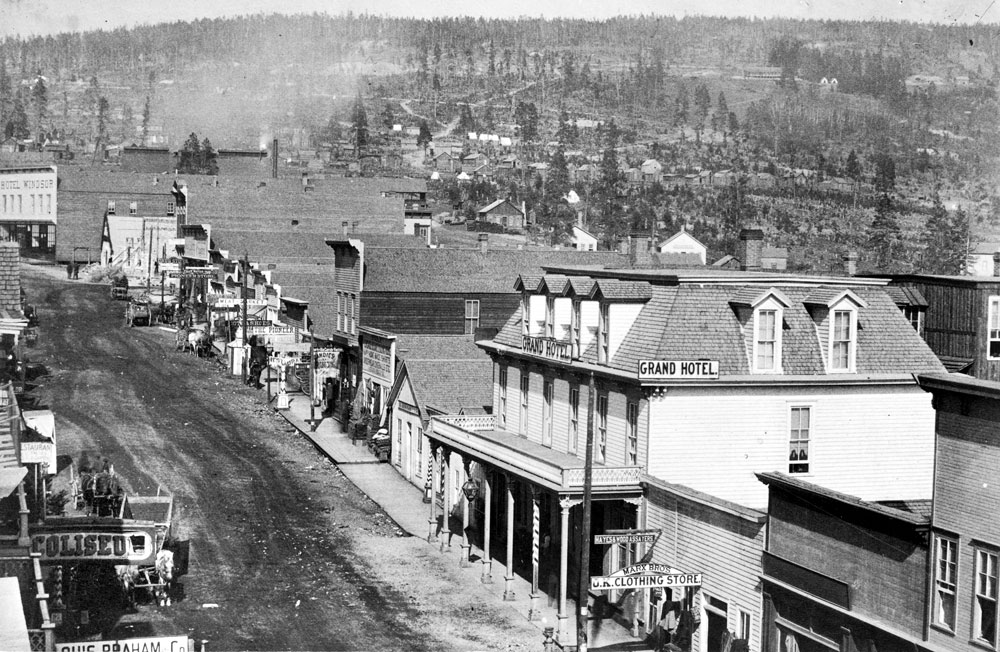

Perhaps on his previous sojourn the Arkansas River burg just hadn’t offered the right inducements. The notorious gambler and gunman was a high roller and Leadville, even if past the apogee of its boom, still boasted the kinds of fast-paced action Holliday preferred. Later that day when he stepped off the train at Leadville’s four-gabled brick depot, Doc was at the summit of his fame, or infamy, seemingly in the pink of health and no doubt looking forward to fattening his bankroll at the camp’s several classy gambling parlors such as the Monarch, the Board of Trade, the Texas House and Mannie Hyman’s Saloon.

But Leadville would not prove to be the bonanza Doc hoped; instead it would sound a death knell for the Georgia-born ex-dentist. He couldn’t have picked a worse place to settle. The piercing cold and thin air of the place quickly awakened the demon of tuberculosis that had slept in remission throughout his days in southeastern Arizona’s high desert. At first he flourished and came to be regarded as one of Leadville’s leading, if also potentially most dangerous, citizens, winning approval for his mild and agreeable temper, which contrasted sharply with his lethal reputation.

He made several trips over the next months, notably to Dodge City, Kansas, in 1883, along with his friend Wyatt Earp and several other noted “shootists,” to help out fellow gambler Luke Short in a squabble between sporting factions in the old cowtown. He also frequently visited Denver. But Leadville was now his home; he always returned there from his travels. He lived in a seven-by-fourteen foot room upstairs in a building at 320 Harrison Avenue, next door to the Tabor Opera house. The structure was owned by Cy Allen, proprietor of the Monarch Saloon. Doc banked faro for Allen in the Monarch and also played profitable poker – what was called “hard cards” in gamblers’ parlance – at the other prestige saloons along the avenue.

But over time his tuberculosis worsened. He steadily grew weaker and sicklier. He suffered several sieges of pneumonia. Never robust, he now became positively fragile. By the summer of 1884 he weighed only 122 pounds. As was his habit when his disease flared up, he began drinking heavily, a habit which interfered with his proficiency at the faro bank.

Inevitably weakness invited trespass. An old enemy from Tombstone days, a swaggerer named John Tyler, headed a coterie of gamblers who, for various reasons including Tyler’s resentment against Holliday for having publicly humiliated him during the Arizona feud, began to pick on his ailing nemesis. To make matters worse, Holliday’s legendary luck at the faro layout deserted him, former friends shied away because of his drinking and he soon grew short of funds. Finally he lost his job dealing for Cy Allen, who for some reason had taken Tyler’s side in the growing dispute between the two old antagonists. Rubbing salt into this wound, Allen hired Tyler to take Doc’s place at his faro table.

As Holliday’s health failed, Tyler and his henchmen pestered him more and more. Finally, on July 21, 1884 some of them cornered him in Hyman’s Saloon and dared him to go for his gun. Unarmed, in obedience to a city policy prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons, Holliday had no choice but to tolerate the abuse. Next day he spoke to a reporter of the incident “with tears of rage coming from his eyes.”

“If I should kill someone here … no matter if I were acquitted the governor would be sure to turn me over to the Arizona authorities, and I would stand no show for life there at all,” he complained. “I am afraid to defend myself and these cowards kick me because they know I am down. I haven’t a cent, have few friends and they will murder me yet before they are done.”

His words, which seem to smack uncharacteristically of fear and self-pity, defined his quandary precisely. Murder warrants awaited him in Arizona where, early in 1882, he and Wyatt Earp’s “posse” of vengeance riders had killed at least three men they suspected of having slain Morgan Earp, Wyatt’s younger brother, in the wake of the shoot-out at the OK Corral. To have gunned down Tyler and his minions would have surely dispatched Doc to an Arizona hanging at the hands of his worst enemies.

Still, it is hard to reconcile such language with Holliday’s formerly cocksure, devil-may-care attitude. Myth has bequeathed us an image of him as cynically and negligently courting death, hoping to die quickly by the bullet rather than slowly by what was known then as “consumption.” Clearly, the actual Doc Holliday clung to life even when beset by bad luck, poverty and grave sickness, just as anyone would. But underneath the seeming weakness lurked another, steelier reality. He had prefaced his remarks to the reporter with the phrase, “If I should kill someone…” Killing was something he knew very well how to do, and would do again if pressed to it. But a killing just then, given his legal liabilities in Arizona, would have been inconvenient to say the least. So the Tyler gang had him in a box.

[InContentAdTwo]

Ironically, it would not be Tyler who eventually forced Holliday to resort to the gunplay he so earnestly wished to avoid. Instead it would be a man named William J. (“Billy”) Allen, a bartender at the Monarch. This Allen has often been confused with the Billy Allen who was an antagonist of the Earp faction in Tombstone, but the two were in fact entirely different persons. The Billy Allen of Leadville was a sturdily-built, pugnacious former policeman and fitness trainer who had reputedly killed a man in Illinois.

Though the Monarch was now affiliated with Tyler and his yahoos, there is no evidence of friction between Billy Allen and Holliday, who had known each other favorably from the earlier period when Doc worked there. Sometime in late June 1884 Holliday borrowed five dollars from Allen, promising to repay the loan in five or six days, or a week at the most, as soon as a man who owed him money satisfied his debt.

However, when the time came to return Allen’s money Holliday learned that his own debtor was tapped out and could not pay. He explained his problem to Allen, who at first seemed unconcerned. But as time passed and Doc still couldn’t pay, Allen grew impatient and insisted on his money. Holliday was broke and tried to borrow funds from former friends, all in vain. Eventually Allen demanded payment, approaching Doc in a threatening manner and giving him till noon of August 19 to make good the loan, “or else.”

Five dollars was worth more in 1884 than it is today, but even in that time and place it was a trivial amount when a thousand dollars might be required for a gambler to “change in” to a high-stakes poker game. That it became a reason for a possible shooting suggests other motives were at work. Holliday believed Allen was “a tool of the gang” Tyler led. While that was certainly possible, it could also be that Allen felt his manhood was at stake – how would it look if he let a washed-up tubercular deadbeat stiff him for a mere fiver? If that was his thinking, it showed how low the once-dreaded Holliday had sunk in the estimation of Leadville’s sporting fraternity.

The few friends Doc had left began to warn him that Allen intended to “do him up” – frontier slang for killing him. Holliday appealed to the police for protection but instead, at Billy Allen’s instigation, an officer searched Doc for a weapon. Resigned that Allen intended to kill him and the authorities would not prevent it, Holliday resumed carrying his nickel-plated .41 caliber double-action revolver. He was “heeled” with it when he walked into Hyman’s Saloon, his habitual hangout, at three o’clock in the afternoon of August 19 – three hours past Billy Allen’s deadline.

He knew Allen would be coming. He stationed himself between the bar and a cigar case near the entrance, slipped his pistol under the bar and waited for his antagonist to show. Doc had been kicked around enough. He had done all he could to avoid a showdown. Now it was kill or be killed – despite his recent setbacks, familiar territory to the “deadly dentist.” In the real world of the Wild West, a gunman always looked to gain an edge; giving your enemy an even break was the same as suicide. Doc’s position near the entrance, with his gun in reach, gave him just the edge he needed.

Allen, at work in the nearby Monarch, had been looking for Doc all day and had spied him going into Hyman’s. Immediately he stripped off his bartender’s apron, shrugged into a coat and hurried out, his right hand in the pocket of the coat as if grasping a gun. To a man who tried to restrain him he blurted, “I am going to hunt this party.” He crossed to Hyman’s and barged through the door; Holliday coolly took his pistol from under the bar, leaned over the cigar counter and fired. The bullet missed, splintering the door-frame, and Allen, suddenly reconsidering his options, turned to flee but tripped and fell and Holliday took the opportunity to shoot again, striking Allen in the right arm between shoulder and elbow.

It happened that a prominent Buena Vista businessman and the editor of that town’s newspaper were just then passing by outside and “were startled by two pistol shots and the whizzing of a couple of bullets in close proximity to their cheeks.” The Buena Vista Democrat of August 21 reported “the murderous missiles grazed the merchant’s phiz and captured a lock from the editor’s auburn growth of hair. The victim simultaneously fell in bloody gore before them, none other than the unfortunate Billy Allen at the hands of Doc Holliday. Since ‘death loves shining marks,’” the paper concluded, “the wonder is that Allen was taken and the others left.”

Holliday surrendered himself to the law. Billy Allen was carried off to receive medical treatment. The doctor who attended him later testified that “the main artery of the arm had been injured” and “he is not out of danger” of death “from blood poisoning.” No gun was found on Allen’s person after the shooting, but in the confusion it could have been misplaced or intentionally hidden by Allen’s friends, and two defense witnesses actually said they saw him with a pistol.

Allen was still recuperating from his wound when Holliday went before Judge W.W. Olds in District Court on August 25 for a preliminary examination on a charge of assault with intent to kill. In his testimony Holliday sounded very much the aggrieved victim of unreasonable malice. Allen, he said, had dunned him repeatedly and when finally setting the deadline told him, “if you don’t pay it, I’ll lick you, you son of a bitch.”

“I said, my jewelry is in soak [pawned] and as soon as I get the money I’ll give it to you,” he testified, but Allen remained unappeased. Holliday told of being warned that Allen was heeled and meant to kill him and of asking for protection from the city marshal, insisting, “I don’t think it is right that one should be disarmed and another allowed to carry a gun; I don’t want to be murdered.” On the day of the shooting, he related, “I saw Allen come in with his hand in his pocket, and I thought my life was as good to me as his was to him; I fired the shot, and he fell to the floor, and fired the second shot; I knew I would be a child in his hands if he got hold of me … I think Allen weighs 170 pounds …; I don’t think I was able to protect myself against him; I thought he had come there to kill me.”

Two witnesses mentioned the difference in size between Holliday and the robust Allen. “Allen is a stout, active man; Holliday is a small man and delicate besides,” said one; and another asserted “Allen is a powerful man and Holliday is a delicate man.” Witnesses for the prosecution told the court they did not believe Allen meant to harm Holliday, only to collect his debt, and that it was Holliday who was “carrying a gun” against Allen.

In the end Doc was bound over for trial and, owing to his ruined financial state, was unable to make bail even after it was reduced from $8,000 to $5,000. He spent some days in jail, causing one newspaperman to speculate, “Should Holliday be obliged to remain behind bars … it would probably go very hard with him, as his constitution is badly broken and he has really been sick for a long time past.” Surprisingly the whole incident revived some of Leadville’s former good opinion of Doc and a number of his old friends warmed to him again. Consequently Tyler lost face and was wise enough to retire into the background. Even Allen felt it necessary, when he recovered, to disavow any connection with the Tyler crowd.

Doc went to trial on March 21, 1885 and was acquitted. He remained in Leadville and, by June, had actually recovered enough of his old savoir-faire to collect a fifty-dollar debt at gunpoint from a tinhorn gambler called Curley Mack. But unwilling to suffer another of Leadville’s frigid winters, he relocated to Denver that autumn.

There, in a chance meeting in a hotel lobby, he had a last emotional reunion with his old companion Wyatt Earp. By then Doc was feeble and failing; Wyatt was visibly moved – an uncommon state for the famously unemotional gunman. Years before, Holliday had saved Wyatt’s life. As they talked, Wyatt remarked, “Isn’t it strange, that if it were not for you, I wouldn’t be alive today, yet you must go first.”

“Goodbye, old friend,” Doc said as they parted. “It will be a long time before we meet again.” He was right. As if trying to defy the inevitable, he spent the cruel winter of 1886-1887 back in Leadville working for Mannie Hyman. But his condition deteriorated, and the following May he traveled to Glenwood Springs to take the sulphur treatments thought beneficial for consumptives. Toward the end he struck up improbable friendships with a Catholic priest and a Presbyterian minister, perhaps laying canny bets on both possible routes to salvation. He died on November 8, 1887. His last words were, “This is funny.”

Charles F. Price is a sometime contributor to Colorado Central unwholesomely interested in Western outlaws. He is a North Carolina author who is trying to relocate to Salida in hopes the cowboy hat he constantly wears will finally fit in. His wife is the former Ruth Perschbacher of Salida. Price has published four historical novels about his native Southern Appalachians, a book about the Revolutionary War and has completed a history of the 1863 Espinosa murder raid.