By Ed Quillen

Editor’s note: Back in April we asked Ed Q. if he’d like to write about the smokestacks, knowing his particular interest in Salida history, especially its sooty, grimy, industrial history. We regret his passing before it finally went to print.

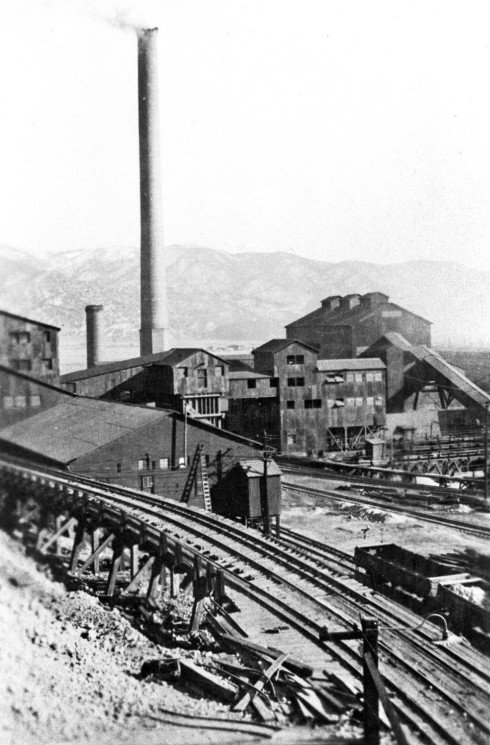

As the saying goes, “The solution to pollution is dilution,” and that’s the reason for a Salida landmark, the big smokestack that sits west of town.

The 365-foot-tall chimney was built in 1917 to carry toxic fumes far away from the smelter, so that the Ohio & Colorado Co. facility wouldn’t have to keep paying off local farmers for damaging their crops and livestock. You could call it an early monument to environmental protection.

The surviving tall stack replaced two shorter flues at the smelter, and to understand why the company decided to erect it, we need to consider the process of smelting, which originated in remote antiquity, perhaps 8,000 years ago when humans began to use copper and tin.

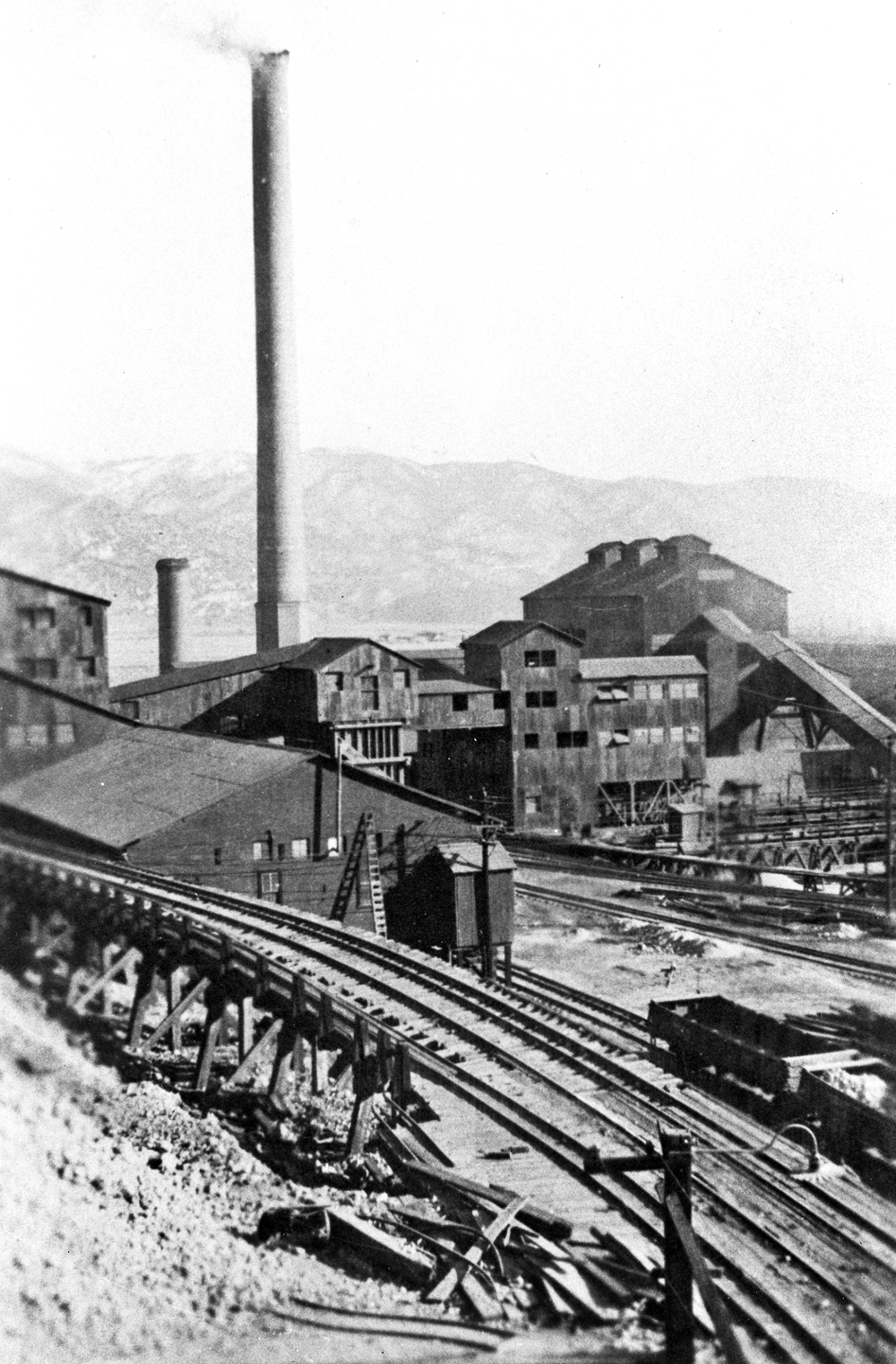

Photo courtesy of the Salida Regional LIbrary.

The ores of central Colorado tend to be sulfides (e.g., Climax mines molybdenum disulfide, and galena mined at the Black Cloud was lead sulfide). The general idea is to convert the sulfides into oxides, then strip away the oxygen to leave just the metal.

Typically the mined ore goes to a mill where it is crushed. Then the metallic sulfide is separated from the country rock by flotation that has the sulfides rising to the surface of soapy water. The result, after the stuff dries, is a powder known as concentrate, and that’s what feeds a smelter.

At the smelter, the concentrate is roasted and the sulfur is replaced by oxygen so that the sulfides become oxides (sulfuric acid can be a by-product). Then the roasted concentrate gets a jolt of carbon monoxide from the furnace. The monoxide bonds with the oxygen in the hot metallic oxide to strip it away from the metal. Carbon dioxide is produced, and the solid result is an impure chunk of a metal. The ground-up country rock generally melts and fuses to form slag, which gets dumped somewhere nearby, often when still molten and glowing.

Note that this is a simplification, and that there are many smelting processes.

Roasting the concentrates can send toxic elements like arsenic, lead and selenium up the stack. If the stack is short, the particles will usually settle nearby and harm crops, livestock, and people. If it’s tall, the fumes will be blown farther away and disperse over a wider area.

As for the smelter that needed the big stack, in 1903 Salida was a major railroad junction in the midst of mining country. Further, there was the “Smelter Trust” put together by Meyer Guggenheim and his sons. Their American Smelting and Refining Co. had the big Globe Smelter in Denver and another plant in Pueblo. The company loomed as a potential monopoly that could drive down the price that mines got for their ores. Thus it was in the miners’ interest to support a competitor, especially one that was closer to their workings.

In the latter 19th century, many mining towns had smelters, and some survived for a long time; Leadville’s Arkansas Valley Smelter, source of those hills of slag you see on your left when you’re coming into town from the south, operated until 1961.

But more modern mining meant shipping the concentrates to a distant smelter. The Climax Molybdenum smelter is in Fort Madison, Iowa, and the Asarco Black Cloud Mine sent its concentrates to a now-demolished smelter in East Helena, Mont., where three smokestacks, one of them 425 feet tall, were blasted down in 2009.

Back to the Salida smelter. Technically, it should have been called the Kortz Smelter, for that was the name of town around it where workmen lived and traded. It was named for company president J.C. Kortz. Even back then, though, the settlement was known as Smeltertown, a name that persists to this day. Some of my friends out there, though, have said they lived in Smelter Estates, Smelter Shores (if along the river) or, up on the bluff, Smelter Heights.

There were many smokestacks in the smelter complex to serve boilers, but there were only three big ones to handle the fumes from the ore roasters. The first one, built in 1902, was 150 feet tall. It was soon followed by a nearby 85-footer. Both were made of local brick from clay mined along the South Arkansas River south of Salida.

Those two stacks provided ample draft for smelter operations. It had a capacity of 1,200 tons a day and employed from 300 to 450 men, depending on business. It kept the railroad busy hauling coal and ore in, and ingots out.

So why the $50,000-plus expense of a 365-foot smokestack made of imported brick when things were running fine with the two smaller chimneys? Salida author Dick Dixon explained it in his 1987 booklet, Smokestack: The Story of the Salida Smelter – (now, alas, out of print):

“Fumes and gases belching from the Ohio and Colorado Smelter were creating an ecological disaster … Trees died on the slopes of the low Mosquito Mountains downwind to the east of the smelter, including those on Tenderfoot Hill … Ranchers who lived downwind found their crops didn’t do as well as they had in the past. Animals sickened and died.”

Ranchers brought lawsuits, and the “company managed to stay out of court by purchasing pollution permits.” For instance, it paid Matt Mautz, a nearby rancher, $250 for the “perpetual right, privilege and license to deposit such smoke, fumes, gasses, vapors, flue dust and other noxious and offensive emanations or the chemical products thereof” on his land.

There were many possible claimants to damages, and some who wouldn’t be bought off. So in 1917 the company built the big stack to waft away the pollution so it would spread over a larger area and thus be less toxic in any given spot. Dixon observes that “the fact that it happened in an age when ecology regularly took a back seat to industry, makes it truly a credit to the men who ran the plant.”

At 365 feet, it might have been the tallest structure in Colorado. The Daniels and Fisher Tower, which still stands in downtown Denver, was the tallest building between the Mississippi River and the West Coast when it was erected in 1910. The Salida smelter stack was 35 feet higher. I wasn’t able to find anything taller built in Colorado before 1917, but there certainly could be something, likely another smelter stack.

The big stack remained in use for less than three years. The smelter closed in 1920 and never resumed production.

What happened? Generally, if you produce metals, war means prosperity, and peace is hell because demand drops. Silver was fetching 96.8 cents an ounce as World War I raged in 1918. In 1921, it had dropped to 62.8 cents.

Zinc fell from 14.4 cents a pound in 1918 to 5.2 cents in 1921. Lead, the stuff of bullets, went from 8.7 cents a pound in 1918 to 4.2 in 1921. Copper plunged from 29.2 cents a pound in 1917 to 12.6 in 1921.

(These are New York metal prices from Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970. Some unenlightened people may find this book boring, buts it’s luridly fascinating to nerdy history buffs like me.)

When the price for a metal falls below the cost of production, mines close. And without a supply of ore to process, the smelter will close, too. That’s what happened to the Colorado & Ohio Smelter.

After the shutdown, there was sporadic talk of re-opening it. There were foreclosures and sheriff’s auctions and unpaid back taxes, with the plant’s machinery getting scrapped and most structures demolished – often the brick was cleaned and used to build Salida houses.

Part of the property was used for a plant that applied creosote to railroad ties from 1924 until 1953 (the saddle-tank steam locomotive which served that plant sits at the Salida Museum). Nearby was Cozinco, a company that used sulfuric acid to recover zinc from scrap metal.

All that remained of the old smelter complex was the two-story office building and the tall stack, which was twice within 24 hours of demolition (it was mistakenly thought to be likely to topple and injure people) before it was deeded to the Salida Museum Association in 1974 after local citizens formed S.O.S. (Save Our Stack).

It’s now on the National Register of Historic Places and has some exhibit panels to explain its lore to people driving the Collegiate Peaks Scenic Byway. When resources permit, the Salida Museum Association would like to augment the displays to explain more about Colorado’s smelting industry.

Ironically, it might have been the stack’s short operating life that saved it. Smelter stacks that were in longer use accumulated health hazards that prompted their removal for environmental protection. But Salida’s stack was relatively clean because it didn’t get much use, unlike Durango’s, which went down 30 years ago.

One smelter legacy is a rumor that goes something like this: “Don’t eat root crops grown around Smeltertown because the soil out there is toxic from the smelter and the other industries.” Or maybe it’s leaf crops, or both, as I’ve heard several variations.

That might have been the case years ago. However, in 1997 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency declared the area a Superfund site. Contaminated soils were removed, and new water wells were drilled for residents.

Chaffee County Extension Agent Kurt Jones said he’d heard those toxic-soil rumors, too, but “I know of no reason why you shouldn’t eat produce from Smeltertown these days.”

A veteran Smeltertown resident, Ann Ewing, explained that “Most of the ground and groundwater pollution came from CoZinCo and the creosote plant, not the smelter.” She points out that “thanks to the EPA which replaced our topsoil, we’ve got the cleanest dirt in the county. This is probably the best place to garden if you’re worried about what’s in the soil, and we enjoy a big garden every summer.” (See story on page 18).

So in less than a century, the smelter site has gone from ranchland to heavy industry to Superfund Site to a garden spot, with an impressive landmark that tells Salida-bound motorists on Colo. 291 that they’re almost there.

Ed Quillen won’t reveal the name of a visiting friend who climbed the smokestack in 1979. But he will point out that Smeltertown is rather upscale in an odd way, since the old cars sitting on blocks there are Volvos, rather than Chevys or Fords.