Article by Marty Rush

Mountain Life – December 2005 – Colorado Central Magazine

ON AUG.16, 2004, I quit my job in the communications department of a large HMO in Denver. A growing dissatisfaction with my life as a corporate mouthpiece had reached critical mass. I was horrified by what I’d become: a suburban commuter who sat in a cubicle all day, cranking out the party line. As editor of the employee newsletter, I informed the Organization’s local staff and physicians about company initiatives and policies, reflecting the ideology of the Head Office in California and regional executives down the hall. I was good at my job. I reduced complex ideas to succinct paragraphs and used clever headlines, quotes and graphics to edify my readers even as they were propagandized, producing a punchy, two-page newsletter each week, one that flattered the right power groups and furthered Leadership’s objectives.

I was the Joseph Goebbels of health care.

I hadn’t set out to be the Joseph Goebbels of health care, although my goal in life did relate to mass communication. My dream was to be a fabulously successful writer. But fabulous success never came. Instead, my journalism degree landed me in corporate communications with the Borg. The Organization had yet to assimilate me, but my creative spirit was on life support. Resistance is futile! In my case, resistance was also insane. I was 54 years old with no assets, a couple of chronic illnesses and a grown child living under my roof. Deep in debt with a spotty work history in a tight employment market. I’d be crazy to quit a paying job with great benefits at a thriving company.

The day I quit was the anniversary of Elvis Presley’s death. This was no coincidence. Elvis’ death day was a significant date for me personally. In an alternate reality that briefly co-existed with our normal one, I was the co-founder of a satiric (some said satanic) Elvis religion. As Reverend Mort Farndu of the First Pres leyterian Church of Elvis the Divine, I enjoyed not 15 minutes of fame, but an entire hour. And in Presleyterian theology, Aug.16 was Transcendence Day, when Elvis became a being of both flesh and spirit, body and soul, two mints in one. What better day to embark on a little personal transcendence?

I went to work that Monday as Reverend Farndu, appearing in my cubicle at Regional Headquarters in gold lame jacket, red silk scarf and aviator sunglasses. I gave two weeks notice and spent the day editing my newsletter and scaring the staff. Nine months later, I was ready to transcend. I’d cashed out my IRA, minus penalties, and the rented duplex I shared with my son was empty, everything we possessed accounted for, including my son himself. Dan wasn’t going off with me to seek Enlightenment, which he gladly would have done, but neither was he going into storage, to charity or the landfill. He was moving into my girlfriend’s house. Devon had agreed to accommodate the lad, although she was really accommodating the lad’s father, an unemployed, asthmatic geezer in the grip of a late-life crisis.

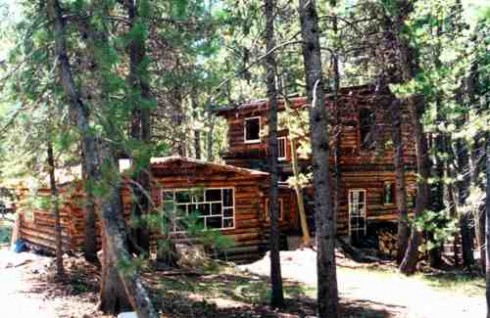

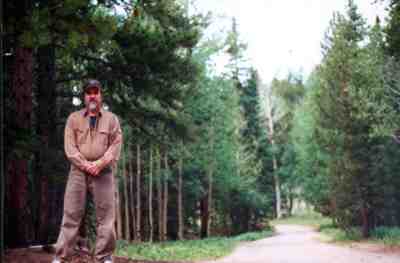

But I did have a Plan. This was not a rout, after all, but a tactical retreat. I was moving back to the log cabin I’d built 30 years before, on a 10-acre mining claim at 11,000 feet, on a now-defunct commune in the middle of a National Forest. My plan was to get back to the land and get my soul free. This was not some naive experiment in self-sufficiency, however. I’d be shopping at the Salida Safeway and (God forgive me) Wal-Mart, but part of Walden did apply: “Simplify. Simplify.” I would be cutting life to the bone — no financial or health care security, no Internet, no TV, no phone — withdrawing from the world, even from the people I loved. I had to get quiet, centered and ignite that divine spark within, be it the Tao, the Buddha, Jesus or Elvis.

****************

Moving back to Earth Mountain was more than a change of physical space. The cabin was a time machine. I was hammering, chopping, repairing, doing town trips for supplies and R&R – it could have been 1975. I’d built the original cabin, now the kitchen, in 1973 and a two-room addition in ’79. It was my primary residence until the early ’80s. Over the past 20 years, it had become a weekend getaway like the other cabins on the land. The commune remained a special place to visit, where old friends returned to eat, drink and make music, to recapture the magic of youth or simply enjoy a beautiful spot in the mountains for a few days.

It took a fortnight to get the cabin in order. I went room-by-room, cleaning, throwing out, organizing. It was Martha Stewart meets Jed Clampett. I gathered bouquets of fresh flowers and trashed rodent-infested furniture. Nailed up Earth tone bedsheets to hide the junk under the kitchen counters. Hung framed pictures and a gyrating Elvis clock, added a dresser and clothes hamper in the loft, this last item getting dangerously civilized, Devon warned. I felt possessed by a weird energy, operating on an alternating current that fluctuated between exhilaration and terror.

I was flying high, working without a net, and like Wiley Coyote okay as long as I didn’t look down.

I welcomed summer with forest creatures great and small. Krishna, the snowshoe hare. A doe who grazed around the cabin. The bat in my loft. (Hard to miss the symbolism there.) One evening, I found a fawn lying under a juniper, hours old, white-spotted and trembling. It was a Bambi moment and the coolest thing I’d seen in 35 years on Earth Mountain, except for the lynx that once crossed my driveway.

On clear nights, I climbed to the Observatory, a 10-minute hike up a rocky outcropping behind the cabin. I watched a new moon set in the west and a full one rise in the east two weeks later, relearned constellations – Scorpio, Libra, the Virgin lying on her back with outstretched arms. (Really.) I saw lots of commercial jets, occasional shooting stars and nothing out of the ordinary. The San Luis Valley was a hotbed of UFO activity. We’d had events on the commune in olden days, like the night I had a Close Encounter of the Second Kind: a warm light bulb flash that lit up the woods with a soft metallic beep like in a hearing test. My friends called it, “the night Marty got bleeped.” I figured extraterrestrials had taken a photograph of my brain for their data bank, and I’d never hear from them again, which was just like aliens — you let them copy your neurons, then they never call. Now I was making it easy for them, spending hours at the Observatory under the night sky, exposed, alone . .

*****************

I saw people, too, mostly on ATVs. It was a plague: buzzing hornets of tourists driving through the woods on riding lawnmowers. It was hard not to wish them ill . . . until one day an ATVer pulled in and asked if I had a phone. His dad had crashed down an embankment and broken his leg. (I hadn’t realized my powers and vowed never to use them for evil again.) Within an hour, vehicles from the state patrol, county sheriff and Saguache fire department were parked down the road, along with an ambulance, search-and-rescue volunteers and curious neighbors. It was a lot of excitement for a Sunday afternoon in the mountains and an impressive turnout of local emergency personnel, reassuring for hermits living in remote cabins and their loved ones.

Once or twice a week, I drove to Salida, an hour away. I stayed overnight with friends, mesmerized by their cable TV, and went to Dick’s Electronics weekday afternoons to watch Jeopardy with the geezers. Otherwise, my social life was whoever showed up on the land, which was almost nobody that summer. It was all part of the magic of geezerdom. The older we got, the less inclined we were to disrupt our lives, pack kids and dogs and coolers with enough food and beer for a month — or a fortnight, at least (I’ve always liked that word and thought it should be used more often) — and drive an hour or three to the mountains, where we lacked running water and tried to climb the hill between Dick’s cabin and Al’s without having a coronary. July Fourth, traditionally a major party on Earth Mountain, drew three celebrants: myself, Devon and a former communer who hadn’t visited in four years.

It was Devon’s first visit of the summer. She was busy at her job as a proposal writer for a company that bid on military base renovations. It was a good time for defense contractors, apparently, and a bad time for getting off weekends to see your sweetie in the mountains. But she was still a perfect fit. She loved the cabin and liked Dan, valued her independence, QNT (quality naked time) and the quiet things in life. And honesty. She admitted she was with me only until she discovered the whereabouts of my secret vast fortune, then it was adios. It had been seven years. Devon was a patient woman.

Dan took the bus to Salida and stayed a few days. It was a party weekend on the land, with full cabins, communal dinners, music, washer games and a son I hadn’t seen in a month. Dan had moved in with me his senior year of high school, when I went from being a weekend father to a Jewish mother. I made it easy for him to be dependent, to live in the basement of our duplex, stay online all night and sleep in the soil of his homeland by day. He was 22 now, easy-going, introverted, eccentric — it was the ancient curse: You should have children just like you! As a child, he’d been a revelation, a lesson in commitment and unconditional love. He was a continuing revelation as an adult, finding his footing with a job and community college, exploring psychology, philosophy and Eastern religion, turning me on to books, music, ideas . . .

I was so blessed in my personal life, it was ridiculous.

The irony wasn’t lost on me. I had nothing on the material level and everything on the emotional one, a strong bond with my son, romance, friends . . . but it wasn’t enough. I needed something more. I needed to plug in my laptop and face the Book.

****************

People don’t choose to be writers, it chooses them. Somewhere in my DNA was an instruction to write. In school, I was off the charts in creative writing in English classes. That need drew me to Earth Mountain — what better place to find my Muse than a log cabin in the woods, one I built myself? Through three decades of adulthood, no matter what was happening in my life, I was writing.

I sold a few stories to confession and men’s magazines, articles to regional magazines, opinion columns to weekly newspapers. And a slew of pornographic novels, the closest I came to self-support, earning $20 an hour at my manual typewriter in the mid-’80s until videotape killed the porno paperback market. I had discipline, produced finished book manuscripts and got them in front of editors and agents. And talent, according to my rejection slips. I had entrepreneurial spirit, self-publishing The New Improved Testament, the Presleyterian bible, and selling a few hundred copies.

I kept my day job.

My latest project was Cosmic Funk. It had started as a memoir — stream-of-consciousness stories about the 1970s, tales of communal life, building cabins and getting snowed in, of love and lust, psychedelic trips and cross-country hitchhiking trips, odd jobs, working underground at the Climax mine — I Walk With the Dead! — entertaining stuff, but not a coherent book. So I was turning the memoir into a novel, an exercise in literary alchemy. A novel meant a linear story, character development and arc, secondary characters, dialogue . . .

I struggled with it. I climbed around Sheep Mountain to clear my head, diverted myself with the odd visitor, town trips, a Rockies game in Denver. Dan visited again, just before Greyhound canceled service to Salida. He’d been biking all summer, losing weight and gaining muscle, buying camera equipment and taking interesting photographs. I loved my loved ones more than ever, but in the end I sat alone at the laptop screen, looking myself in the face. The image was vague, sometimes blank . . .

In the opening scene of The Big Chill, a minister asks, “Where did Alex’s hope go?” referring to the man whose suicide brings the characters together. I had to answer that question. Did I still hope to succeed as a writer? Or had I burned my last bridge, quitting the Organization? Friends said they admired my courage, they called me an inspiration, but none of them were leaving their jobs, giving up their security and moving back to the woods. Maybe they knew something I didn’t. Maybe I should have taken the Rutledge Fellowship. I struggled with that, too.

*********************

Summer gave way to fall, and I contemplated winter. At 11,000 feet, winter was a reality test. Snowflakes were beautiful, delicate things, but when they ganged up it could get ugly. The road could close anytime between Halloween and Christmas, depending on the weather and what you drove. Winter was possible on Earth Mountain — and enjoyable — if you were physically and mentally prepared. I was neither. My tactical commander vacillated, unsure how far to retreat.

Venus moved into conjunction with Jupiter, which meant something. The bat in my loft went to sleep, but a pack rat showed up, scrabbling on the logs all one night and dead the next. Coyotes by the Observatory woke me with sounds like Luca Brasi being garroted in Tattaglia’s bar. I listened to talk radio, following a daily regimen of anger therapy, supplemented by intermittent doses of cable news in Salida. It wasn’t just me – the whole world was going mad. I had acute paranoid flashes about my isolation at the cabin, being assaulted by weirdos on ATVs. Then I realized: I was the weirdo. The tourists weren’t coming anywhere near me. I took some comfort in that.

Devon made a surprise visit, driving down on a Saturday and back on Sunday – I took some comfort in that, too. During a rare party weekend on the land, I hosted dinner one night – it was a refreshing change-of-pace seeing my monastic cabin charged with people energy. Dan went to Seattle and Victoria, British Columbia, for a concert and to visit Internet friends, now he wanted to move there . . .

It was the orangest autumn since records have been kept. Aspens turned orange gold, orange red, orange orange, even full red. Afternoons were still comfortable, but it was noticeably colder at night and in the morning. The cold triggered something in my brain — I started getting firewood almost every day. I wasn’t “doing a Baby Doe” this winter, as Devon worried, but I wasn’t selling the Matchless either. I’d gotten in a groove with Cosmic Funk, building character, plotting a trajectory, hearing an Omniscient Narrator voice. It was fun and made for a viable novel, but it was slow work. I’d revised two chapters in four weeks — two out of 20. It would take a year to finish the book, longer to sell it and see it published. I’d be broke in months . . .

Devon visited again in early October, ushered out by a Sunday snowstorm. I went to Salida for some mindless but enjoyable NFL action and drove back Monday in six inches of snow. The Nissan pickup did well in four-wheel high with 300 pounds of sand in the back. It was a blast of winter on the land, aspen leaves gone, snow covering the ground and piled in the pine and spruce branches. Once I got past the shock, I fell in love with it. I’d forgotten the greatest allure of winter on Earth Mountain: its simplicity. The world was clean, stripped down to the basics. Outside: snow, evergreens and sky. Inside: heat, food and writing.

It was Yom Kippur that week, the Day of Atonement, my birthday, the start of rifle season. Conjunctions were happening all over the place. I had a stockpile of firewood and food, a charged laptop, snowshoes and the belief I could walk three miles to a plowed road when the time came. And when another time came, I would gird my loins and return to the world, find a job and a place to stay and get by with a little help from my friends until I could retreat back to the cabin . . . In short, live like a hippie again.

I was comfortable with that.

At the peak of the psychedelic autumn, Dan gave me an essay by Philip K. Dick, the science fiction writer. In the essay, Dick talks about certain odd humans who seem to know instinctively what they should not do and who will refuse to do it, even if it brings terrible consequences, people who “cannot be compelled to be what they are not.” I was never a 9-to-5 commuter from the suburbs, although I played one on TV for years. To quote the philosopher Samuel Davis Junior, I had to be me, and me was a writer who lived in his cabin in the woods, watched for aliens and wrote. Period, paragraph, end of story.

Marty Rush was born and raised in New York City. Since arriving in Colorado in 1971, he has worked as a construction laborer, antique refinisher, typesetter and corporate communicator. He is currently incommunicado, but can be reached at P.O. Box 1062, Salida, CO 81201.