Article by Hal Clifford

Environment – December 2003 – Colorado Central Magazine

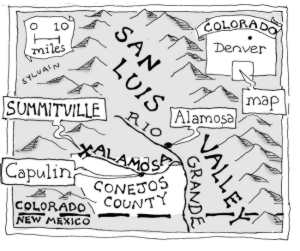

THE SAN LUIS VALLEY is a high desert with table-flat farmland surrounded by mountains. It’s a slice of Colorado that feels like New Mexico.

Just over a decade ago, the Valley made national headlines when cyanide holding ponds at the Summitville gold mine failed spectacularly and poisoned the Alamosa River, which runs through the village of Capulin. The 1990 spill killed everything living in a 17-mile stretch of the river — and turned a national media spotlight on the dangers of modern mining.

Here in Conejos County, the spill also forced residents to recognize that they had mismanaged the river for a generation. Summitville was the final insult.

Now, more than a hundred local people are rebuilding the Alamosa into a river that, while not pristine, will look and act much more like the river their grandparents knew. “We’re farmers and ranchers,” says fifth-generation farmer Alan Miller, 42, from beneath a sweat-stained hat. “It’s not a bunch of 30-something yuppie environmentalists.”

A sorry past

The Alamosa River’s problems began in 1970, when heavy rain blew out an upstream dam that was under repair, filling the river with a cascade of channel-clogging silt. That winter ice dams created floods that inundated Capulin. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers responded by doing what the Corps did best back then; they turned much of the river into a ditch.

The flooding subsided, but new problems arose. The channelized river carved into the alluvial soils, slicing 10 feet down in places. The water table dropped, drying up the streamside riparian areas and adjacent fields. As the river ate into the earth, dozens of ditch companies that drew water from the Alamosa found their headgates — which direct river water into irrigation ditches — perched high above the river.

In the late 1970s, Miller’s uncle tried to create a coalition to restore the river. But his effort foundered, and a decade later he died. Nothing changed until the Summitville holding ponds — which were full of heavy metals and cyanide used in the heap-leach gold mine — failed. The mining company declared bankruptcy in 1992, and the area became a Superfund site.

“Summitville really kicked us in the pants,” says Miller. While the state and the Environmental Protection Agency tackled the pollution generated by the spill (a cleanup that has cost $160 million to date), Miller and other county residents revived the effort to restore the river’s channel and natural functions.

They formed the Alamosa River Watershed Foundation in 1999, a nonprofit that can apply for and accept grants.

In 2000, the foundation completed a small demonstration project near Ignacio Rodriguez’s horse ranch, and this spring, tiny cottonwood seedlings were sprouting. Rodriguez, 76, used to catch his limit of brown and rainbow trout in the river here. Restoration, Rodriguez says, “would very definitely give the community a sense of constructive involvement. They would have accomplished something.”

In Conejos County, the second-poorest county in Colorado, that would count for a lot.

Aikido engineering

“My interest is to fix the river,” says John Shawcroft, 78, who ranches on the meadows at its eastern end and heads up the Alamosa-La Jara Water Conservancy District. Better songbird habitat isn’t at the top of Shawcroft’s wish list, but a river that gets farmers more water will also benefit the other creatures that depend on it.

People may not agree precisely on what they want for the river, but they know that “they don’t like the way it is,” says Ben Rizzi, with the La Jara field office of the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Miller, the foundation field coördinator, intends to place 9,000 refrigerator-sized boulders in 4.5 miles of river this year. The rocks won’t be used as riprap along the banks; rather, they’ll be placed in the river to direct the flow of the river upon itself, to slow and pool its waters. It is the aikido form of civil engineering.

“We plan to shorten the stream’s evolution by a hundred years,” says Miller, who adds that the foundation will plant grasses and trees to stabilize the river’s banks. In places, the river will return to its old meanders. Sediment will pile up where there is only cobble now, and willows and cottonwoods are likely to sprout soon. The water table will rise. Ranchers will move their cattle out of the riparian zone for two years, while people see what the new river looks like and decide what happens next.

Miller’s project covers less than 10 percent of the river’s length. But it has taken a generation to get this far. As Miller strolls the bank near Rodriguez’s ranch, he recognizes that he is building not only a river, but also a community of people who are invested in the waterway.

“This is what the river is about,” he says, pointing to a headgate. “We’re using it. But we can use it wisely. You’ve got to give the resource back to the people. They’ve got to manage it. Who else is going to take care of it in the future?

“If we do that,” he adds, “there probably won’t be another Summitville.”

High Country News (www.hcn.org) covers the West’s communities and natural-resource issues from Paonia, Colorado. The author recently moved from Telluride, Colorado, to Massachusetts.