Article by Allen Best

History – November 2008 – Colorado Central Magazine

THREE INDIVIDUALS, each in a different way seminal to the Colorado ski industry, have died this year. “They were a different breed,” some have said, which may be true. But the landscape was also different when D.R.C. Brown, Earl Eaton, and Merrill Hastings came of age after World War II, sowing their seeds and wild ambitions, helping make Colorado the center of North American skiing and the new amenity-based economy that now has such a grip on large portions of the West.

These three were alike in many ways, but also different. Two were born into lives of relative comfort and security. One was not. Two passed through Camp Hale. Two and perhaps all three were horsemen. All were adventurers.

Following are sketches of the three men, some of the material stitched together from stories in the Aspen, Vail and Denver papers, some of it from my own personal reporting and relationships.

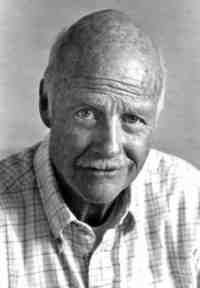

D.R.C. Brown

1912-2008

CEO of Aspen Skiing Co.

Two things were salient above all else in the sketches of D.R.C. Brown after he died in March at the age of 95. First, he was the pilot at the Aspen Skiing Co. during its time of giant expansion. During that time, from 1958 to 1979, Aspen sent out tentacles to Breckenridge in Colorado, Blackcomb in British Columbia, and Fortress Mountain in Alberta.

When Brown became president and chief executive officer of the company in 1958, it had three lifts and a staff of 40. When he left the company in 1979, there were nearly 1,200 employees and operations in three countries.

Remarkably, Brown’s father, David Robinson Crocker Brown Sr., had been among the major figures in Aspen’s silver era. He did it by pluck, and probably with luck. The senior Brown had been working at Black Hawk, a mining camp west of Denver, and was headed to New Mexico when he was drawn by the mining excitement in the Roaring Fork Valley. That was in 1880, and Brown drove a wagon from Buena Vista across Cottonwood Pass to Taylor Park and the vicinity of Crested Butte.

From there it was another hump across the Elk Range and into the emerging camp of Ashcroft, whence he eventually made his way to Aspen.

In Aspen, the senior Brown became a millionaire mine owner– with properties on Aspen Mountain, where the ski area is now– and he was wise enough to diversify prior to the silver crash of 1893.

Darcy, the junior Brown, was born in 1912, when his father was 48. Although he summered in Aspen, he was reared mostly in Denver, and attended high school at a boarding school in New Hampshire before graduating from Yale University in 1935 with a degree in economics, and a minor in French.

After that, Darcy was a roughneck in the oil fields of Colorado and Wyoming, later working as a landman and in other oil patch jobs. During the late 1930s, he skied at Berthoud Pass, near Winter Park, but also at Aspen Mountain. There, a ski trail had been laid out by Swiss skier Andre Roch.

During World War II, Darcy Brown hoped to become a pilot in the Navy, but was too old. Instead, he was a skipper of a PT boat in the South Pacific. A more famous PT boat skipper was John F. Kennedy.

After the war, Brown bought a ranch near Vernal, Utah, and then at Carbondale. He also served one term, from 1953 to 1957, as a state senator in Colorado.

HE MARRIED WELL (as the saying goes). His wife was a descendant of the Boettcher family from Denver, whose wealth was derived from the silver mines of Leadville. The Boettchers used their fortune to create the Ideal Cement and Great Western Sugar factories that were so important in Colorado for much of the 20th century.

The Brown family’s ownership of a mine on Aspen Mountain became the conduit to D.R.C.’s involvement with the skiing company. The family leased the hundreds of acres to the ski company, and Brown, who lived in Carbondale, became the managing director and then chief executive.

The Aspen Daily News explains that under Brown’s purposeful guidance, the company acquired Buttermilk Mountain; in 1964 it agreed to manage the launch of the Snowmass Ski Area; and, in 1970 it purchased Breckenridge.

By 1977, Aspen had also taken over Fortress Mountain Ski Area, near Banff; acquired 1,200 acres in Washington state in an effort to start the Early Winters ski area; obtained an interest in a Spanish ski area called Bazuiera-Beret; and secured the contract from provincial officials in British Columbia to build and operate the Blackcomb ski area.

Brown also helped form Colorado Ski Country USA and the National Ski Areas Association. He was perceived as the most powerful man in Aspen, and he enjoyed the role, acquaintances said — even if that often meant the hostility of locals. Indeed, he seemed to take a perverse pleasure in their antagonism.

For example, Aspen for many years gave away season passes to all teachers and other locals. Bill Coors, 92, of the brewing family, was on the board of directors of Aspen then, and told Brown that he didn’t give away beer to all people in Golden just because they lived there. Coors told the Rocky Mountain News that he remembers Brown being burned in effigy in Aspen after the free skiing ended.

In 1976, in an effort to get local skiers to ski less on an increasingly crowded Aspen Mountain, Brown started requiring an $8 daily surcharge, on top of the $200 season pass. That led to a Congressional investigation and a demand from the Forest Service that Brown change his pricing policies. Brown refused — and won.

Michael Kinsley, one of the architects of the stop-growth movement in Aspen and Pitkin County during the 1970s, told Brent Gardner-Smith of the Aspen Daily News that over the years he developed a strong respect for Brown.

“One of my regrets as a commissioner is not dealing with the old-timers who got the community through the Quiet Years here in a respectful way,” Kinsley said, referring to Aspen’s interlude between mining and recreation fortunes. “In our zeal, we were pretty disrespectful.”

Brown blocked the Teamsters Union when it attempted to organize the ski patrol.

“He wasn’t going to be negotiated into anything,” said Jerry Blann, now president of the Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, who joined Aspen in 1970 as a management trainee and later, in the 1980s, became president. “Yet he was truly a gentleman. He was a pretty sophisticated guy, but he could get down in the dirt with the best of them,” Blann told the Daily News.

A portrait compiled by John Colson of The Aspen Times similarly portrays Brown as a man of contrasts. He seemed humble, yet was firm and clear. Most prominent of all was his love of outdoor and physical life.

BROWN HAD BEEN a good boxer in his youth, broke ribs while kayaking the big rivers of the West, and broke more ribs yet while trying to break a horse. He loved the ranch life, and after his years as ski executive he operated a ranch in Australia for 16 years. Later, returning to Colorado, he had a ranch near Creede, where one of his daughters now lives.

Brown also loved poetry. Even after a minor stroke that occurred shortly before his death last winter, he was watching the news on television and complaining about President George W. Bush, when he recited the entire poem, “Kubla Khan.” But it wasn’t just familiar poems he could recite. Even to the end, he surprised his children with poems they had never heard before. He also wrote some poetry of his own — including some that demonstrated his bawdy sense of humor.

Brown skied until he was 90, and rode a horse until last summer. Finally, he gave that up, too. “Well, I’ve been needing help to get on, and now I need help to get off, and that hasn’t happened since I was 3 years old. I think it’s time to give it up.”

He was 95.

Earl Eaton

1922-2008

“Discoverer” of Vail Mountain

Everybody knows that Vail was the gleam in the eye of Pete Seibert. Those who know a little bit more also know that it was Earl Eaton who showed Seibert Vail Mountain one snowy day in March 1957.

It’s probably true that Vail would have happened eventually — with or without Eaton. The mountain just had so much going for it: foremost its intermediate slopes in all directions, but also its relative proximity to Denver’s population and its major airport.

But Earl Eaton, who died in May at the age of 85, was the prospector, and Vail was the gold mine of his era. Eaton was not at all a vagabond blueblood, like so many of the ski industry pioneers. Rather, he was a blue-collar guy, good with a wrench, but just as adventurous as any of the rest. He rafted from the Colorado headwaters to Lake Mead before such endeavors became easy or fashionable. He ski bummed in Aspen. And he was always on the make for treasure, whether gold, uranium, or some new ski area.

It was, said Cliff Thompson, a former journalist in Eagle County, the journey that mattered to Eaton. He lived for the day and was content with it. “He had his 15 minutes of fame — and he didn’t care.”

Eaton was born ten to fifteen miles west of Vail Mountain, on a ranch along Squaw Creek (now part of the Cordillera real estate complex). Ranching then was a difficult proposition, but he got through high school. He skied then, too, and recalled years later having looked up the valley to what is now called Game Creek Bowl, a part of Vail’s skiing operations, and wondering about the skiing potential.

As storm clouds gathered over Europe, Eaton helped cut ski trails (now long abandoned) on Red Mountain near Glenwood Springs as a member of the Civilian Conservation Corps. He also took up ski racing in Aspen. In 1942, he helped sculpt Eagle Park into the Army base called Camp Hale, home of the 10th Mountain Division. Eaton, however, became a member of an Army engineering unit and was shipped to Europe.

After the war, Eaton worked in the molybdenum mine at Climax and also the gold mines at Kokomo, a town now buried under tailing piles from Climax. He was also at Ski Cooper, the former 10th Mountain Division ski area, and the ski area at Climax. He helped install the first snowmaking system in Colorado at Ski Broadmoor, and later worked at Loveland. Eaton also worked at Aspen, on the trail crew and ski patrol, which he supervised.

The story that seems to best capture Eaton’s adventuring spirit was about a trip during his Aspen years. He and buddies obtained pontoons used to create bridges during World War II. They rafted from Aspen down the Roaring Fork to the Colorado River at Glenwood Springs, and hence to Lake Mead, near Las Vegas, Nev. He was never much of a time-clock puncher.

One persistent goal of his was to find the mythical gold treasure that had been discovered — and then lost — in the mountains south of his old homes at Edwards and Eagle. In the 1950s, during the Cold War rush for uranium, Eaton was prospecting across the West with a Geiger counter in hand. Once, while looking in a side canyon of the Colorado River in Utah, he and companions thought they had found the mother lode. Later, they discovered that they were in the fall-out zone from a nuclear-bomb explosion.

For those in Aspen during the 1950s, the biggest hunt was for the next ski area. Seibert, who had dreamed that dream since childhood, was there. Others in Aspen also dreamed of creating another Aspen, and one of those dreamers was Eaton. He had in mind at least two mountains in his native Eagle Valley, and in 1955 he skinned-up what we now call Vail and Beaver Creek (Grouse Mountain). He had at least one companion, Lefty McDonald. As related in the Vail Daily, McDonald recalls looking down on the Back Bowls with Eaton, and surmising that with 123 inches of powder, there would be terrific skiing.

Two years later, Eaton skinned up the mountain again, this time taking Pete Seibert. Seibert, although he had trained a few miles away at Camp Hale, was unfamiliar with the mountain and its potential. A week or so later, Congress authorized I-70 west from Denver. Six years later the ski area was open.

Eaton did all right, but he never got rich. He was a key figure in getting the ski area up and running. While others were good at glad-handing the swells, he was good at managing primitive chain-saws and greasy monkey wrenches. He had a job for the rest of his life. But he was always looking to the next big thing. He thought for sure it would be snow bikes, but it never really panned out. However, he did get to ride his bike until he was in his 80s on Vail Mountain, the only person so authorized.

Although Eaton never quite got the same attention as Seibert, an Eaton Plaza was anointed during the 1980s in Vail, at the top of Wall Street. And when Eaton died, both the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times ran major obituaries, and his son Carl shared some recollections about him in the Vail Daily. Eaton got his 15-minutes of fame and then some.

As for myself, I talked with Eaton briefly several years ago. “There’s a story about a connection between the creation of Vail and Mount of the Holy Cross,” he told me. “But it may just go to the grave with me.”

In December, after news of his cancer had been announced, I talked with him again, and made plans to visit, hoping to probe that dangling comment. Then I got busy trying to make a living — too busy. When I dug myself out, there was no answer on his phone.

I still wonder about what role Holy Cross had in the creation of Vail.

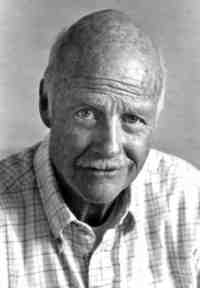

Merrill Hastings

1922-2008

Ski magazine publisher

The night my appendix ruptured I was talking to Merrill Hastings on the telephone. That was in 1997. As he talked from his home near McCoy, between Vail and Steamboat Springs, I listened — and got sicker and sicker, able to only grunt acknowledgment. When we finally finished 45 minutes later, I felt as lousy as I’ve ever felt in my life. I don’t know whether Merrill knew anything had changed.

Boy, he could talk. In the last decade of his life he was on the phone constantly with scores of people, maybe hundreds, entertaining and challenging us and, at some point, wearing us out. “A troublemaker,” said one person. Yes, Merrill stirred up every pot he was in, but that doesn’t quite get at who he was. He was always sure of himself and assured of the rightness of his cause.

Often, Hastings was right about things. But his pursuit of principles was usually overshadowed by his lion-like roaring. It was, says my old newspaper boss, Cliff Thompson, “his method, not his madness.”

HASTINGS, WHO DIED IN LATE May at the age of 85, had a lot to talk about. He was part of the post-World War II migration to Colorado that transformed the mountainous regions. He abetted the rise of the ski industry in his role as a magazine publisher, and helped secure the Olympics for Colorado in 1976. Later and along the way, he argued for wilderness preservation and against the indiscriminate war against bald eagles, bears, and other wildlife predators. Even into the 21st century it was a point of dispute with Priscilla, his wife of more than half a century, that she had once shot a coyote in their horse pasture. He rode horses well into his 80s. He lived large and he lived well.

Hastings was, as near as I can tell, a Boston blue-blood. He grew up in an inner-ring Boston suburb, went to a prep school and became a skier early in life. Skiing was a sport for the wealthy before World War II — unless you lived in places where it snowed a lot. Not surprisingly, Hastings ended up in the 10th Mountain Division. While at Camp Hale, he confided to me that one time he had skied across the Gore Range, spending a Saturday night at a miner’s cabin at Robinson, a mining town now buried under tailing piles. He was a young guy, infatuated with the miner’s daughter. A “dolly,” he might have called her in later years, because he said things like that.

At Camp Hale, he injured his shoulder, and therefore ended up in Italy in another capacity, as a medic in the American Field Service. It was, he told me later, rather like a movie, with larger than life figures. After the war he returned to Bowdoin College, a small liberal arts school in Maine with a history of graduating presidents and other VIPs.

But Hastings wasn’t content to be at any place other than the front of the room, or better yet, outdoors. He came out West, where he helped clear the trails for Arapahoe Basin, directed the Berthoud Pass ski school and, in 1948, started a magazine called variously Western Skiing and Rocky Mountain Skiing, later shortened to just Skiing. He also started a trade magazine for ski-sector retailers. He sold Skiing in 1964.

In 1965, he founded Colorful Colorado magazine. It had a centerfold of gorgeous scenery -treating the Colorado mountains rather like Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Magazine treated the female body, said Denver Post columnist Ed Quillen. Hastings celebrated the state’s history in a tourist-sort of way, but also waged war on its past: logging, mining, and the extermination of predators. In one memorable article published in the 1960s, Hastings argued against the invasion of a wilderness area in the Gore Range by Interstate 70. He called it the Battle of Red Buffalo, and although he hardly did it alone, his voice was powerful. The route was kept on Vail Pass.

Habits die hard. In the late 1980s, he was still arguing loud about this and that. I especially remember a land use dispute he had with the Bureau of Land Management regarding King Mountain. Hastings used both his considerable bluster and charm into persuading federal land managers to adopt a compromise. The land in question would be fenced off to motorized use, but logging and even mining would still, at least in theory, be permitted. Like others, Hastings had recognized that the threat of motorized recreation was greater than the old extractive industries.

Perhaps Hastings’most colorful role was in securing the 1976 Winter Olympics. In his telling, the scheme was hatched at what was then his weekend getaway at Genesee, in the foothills west of Denver. The idea had legs. He was full of insider stories about the work in both Rome and in Sapporo to secure the bid. He was also told how the Denver Olympic Committee, peopled by incompetents and the arrogant, lost the trust of Coloradans. That was a large part of why Colorado voters rejected the Olympics.

BUT THE OTHER REASON the Olympic funding was yanked was the reaction against Colorado’s hell-bent growth of the 1960s and early 1970s. For that he blamed Dick Lamm, and although Lamm was quoted in the obituaries of Hasting as saying that he and Hastings later became friends, I doubt it. Hastings in 2002 called me, complaining bitterly. Lamm, he said, had denied Colorado its rightful place to glory.

Along the way, Hastings gave me lots of advice, virtually all of which I have disregarded — some to my own loss. He was a colorful individual, annoying, brilliant, and a pleasure to know. Sometimes, when I was at his ranch, he would point out some high peak in the distant Gore Range, and ask me to help define it -what the name was. He cared about his animals, his mountains, and also his principles. In so many ways, Hastings symbolized the Colorado mountains in the second half of the 20th century, what you might call hard-nosed gentrification. I miss him, warts and all.

Allen Best has edited newspapers in Kremmling, Winter Park, and Vail, and now free-lances from the I-70 corridor.