Article by Lynda La Rocca

History – November 2005 – Colorado Central Magazine

THEY DON’T PAY TAXES or write impassioned letters to the editor. And they definitely don’t vote–at least not in Central Colorado. Nevertheless, they’re considered an important constituency in Leadville and Lake County.

They’re the “residents” of historic Evergreen Cemetery, whose tombstones tell sometimes poignant, sometimes hair-raising tales about life and death in a rip-roaring, frontier-era, silver-mining boomtown.

Like many old cemeteries, Evergreen has both well-tended and overgrown areas. Established in 1879 and located in Lake County just outside Leadville’s northwest boundary, the cemetery is divided into 12 sections. While half are owned and maintained by religious or fraternal organizations, several are privately owned. And as in many communities hosting similar historic graveyards, the question periodically arises as to who, exactly, is responsible for the cemetery’s upkeep.

During the past two years, John Piearson has spent his own time and several hundred dollars of his own money to help maintain Evergreen Cemetery. A Leadville resident since 1972, Piearson rakes leaves, removes debris from around tombstones–and tells anyone who will listen that not enough is being done to preserve the cemetery.

“Evergreen contains so much historical information,” Piearson says. “These are the resting places of people who helped build Leadville and who made it what it was. And it’s important to make sure that they’re remembered.”

He gets no argument there.

“Of course, Evergreen deserves a certain amount of government attention,” says Ken Olsen, Chairman of the Lake County Board of Commissioners. “And there’s no question that there’s community support for maintaining the cemetery. But local government can only do so much; it can’t do everything for everybody. We have to prioritize,” Olsen continues. “And frankly, based solely upon all the other items that the county is dealing with–from ASARCO’s recent bankruptcy to [federal Environmental Protection Agency] Superfund sites to water-use issues–I would hesitate to get further involved with the cemetery. We have respect for the deceased, certainly, but our first responsibility must be to the living.”

That “respect” is evident in the fact that, despite limited manpower and resources, the city and county regularly join forces to maintain Evergreen’s grounds ” . . . for the benefit of the community, and because it’s the right thing to do,” says Olsen.

Lake County Road and Bridge Director Brad Palmer estimates that the county spends at least $7,000 annually on cemetery maintenance, cutting trees, removing branches, graveling and grading unpaved roads, even plowing snow in winter to provide access for the occasional funeral procession.

And each spring, the city of Leadville spends a month or more and approximately $5,000 hauling away tons of tree limbs and other debris from cemetery grounds, says Mayor Bud Elliott.

“We have no responsibility for the cemetery; it’s not even within city limits,” Elliott points out. “Yet we do this anyway, just to be nice to the community.”

BUT WHAT ABOUT preserving Evergreen’s headstones–some ornately carved white marble and granite, others just two wooden sticks lashed together to form a cross–asks Piearson. He would like to see a civic or historical organization take on the cemetery as a preservation project.

Finding such an organization, though, is easier said than done.

“First off, I don’t think Evergreen is as ‘broken’ as some people feel it is,” says Olsen, a Leadville native who has relatives interred there. “Second, you could say, for example, that old miners’ cabins are deteriorating around the county, and they need to be preserved, too. But the fact is, you can’t preserve everything.

“As far as Evergreen is concerned,” he continues, “the challenge would be to find a group of people with a significant interest in it, people who are willing to focus on determining exactly what work needs to be done there, and who would then write a preservation plan and secure funding. And then, if you can, you’d support the devil out of them.”

Olsen’s observations are echoed by fifth-generation Leadville native and Colorado Mountain College associate professor of humanities Neil V. Reynolds, whose annual guided tours of Evergreen Cemetery have become a Halloween tradition.

“[Evergreen] is not falling apart,” notes Reynolds, also a private-practice lawyer and municipal court judge who spent summers as a law-school student mapping cemetery sites. “It looks pretty much the same now as it did then. Ideally, though, there should be some supervising agency obtaining grants to maintain the place for the future.”

WHEN EVERGREEN CEMETERY was established, the November 8, 1879, issue of the Leadville Weekly Herald declared confidently that this new “City of the Dead … will be the most beautiful cemetery in the state.” And Evergreen’s manicured grounds did indeed prove a fitting repository for the remains of the departed in a frontier city of Leadville’s burgeoning economic stature.

Sloan Lee, who died on November 18, 1879, within a week of the filing of Evergreen’s incorporation papers, was one of the first to go to his “long home” there. Lee’s small, white-marble headstone bears an appropriate inscription for a life that ended in a high mountain valley: “I will lift up my eyes over the hills from whence cometh my help.”

Shortly thereafter, Evergreen welcomed the first of its many infamous denizens. On November 20, 1879, an outlaw named Edward Frodsham was lynched, along with his partner, by a shadowy group of vigilantes that frightened the populace almost as much as did the outlaws. That same evening, H.A.W. Tabor, the flamboyant and fabulously wealthy silver baron, unveiled his namesake Tabor Opera House. Tabor, who was also one of Leadville’s founding fathers, had built the opera house in an attempt–unsuccessful, considering the day’s earlier events–to inject culture and refinement into the rough mining town.

ALSO LAID TO REST in Evergreen Cemetery was 15-year-old Gertie Hosmer, whose miserable family background, precipitous marriage, and subsequent suicide mesmerized–and horrified–the local citizenry. When this “pretty candy girl,” who ran a fruit and candy store on property leased to her by Tabor, eloped with a gambler named John Hammer, her mother and two brothers armed themselves with bowie knives and guns and took to the streets, seeking revenge.

After hiding out for several days, Gertie saved her husband’s life by returning to the family she said had “misused” her. Then, on the final day of 1879, she pressed the muzzle of a loaded revolver to her bosom, and fired.

The bullet passed completely through Gertie’s body and her demise was deemed imminent. Instead, Gertie lingered for two weeks, alternately fading and rallying and causing tremendous confusion among her doctors, as evidenced by this account in the Leadville Weekly Herald: “She took one long breath, and throwing her arms over her head, was thought to be dead. Her physician said it was her last breath; but a moment later, the little invalid, to the surprise of all, started to sing, and did not stop until she had sung a verse of ‘The Sweet Bye and Bye.'”

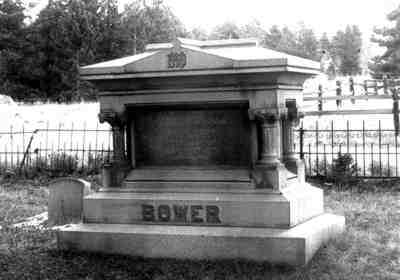

Joining Gertie in sleeping “the sleep that knows no waking” at Evergreen was Leadville Mayor Frank H. Bower, who died on July 16, 1888, of injuries sustained during July Fourth celebrations. Bower was struck by a large rocket or firecracker as he and his wife strolled down Leadville’s main street of Harrison Avenue, the victim of what was proudly proclaimed “the only accident of the day” by the Leadville Evening Chronicle. It’s a declaration that probably gave his wife scant comfort.

Evergreen Cemetery also holds the remains of John B. “Texas Jack” Omohundro, a Confederate Army soldier, journalist, schoolteacher, and actor who appeared on stage with both “Wild Bill” Hickok and William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody. There’s even a burial site for someone named John W. Booth, a cabinetmaker who died on December 31, 1916.

WHILE THIS BOOTH admitted only to being a member of the illustrious family of thespians that spawned President Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, some speculate that he might actually have been the assassin.

John W. Booth’s true place in history is just one of many secrets guarded by Evergreen Cemetery. Those secrets include the specific number of burials that have taken place there over the past 126 years. Although the figure of 25,000 is commonly used, the cemetery contains hundreds of unmarked graves, among them Gertie Hosmer’s. Hundreds more graves, particularly in the two “free” or paupers’ sections where the county historically paid for burials, are distinguished only by cracked wooden boards and crosses from which the inscriptions have completely faded.

So while it’s clear that Evergreen Cemetery is much more than a mute relic from another age, its silent stones must, at least for the time being, await a generous benefactor dedicated to restoring, maintaining, and preserving their historic glory. H.A.W. Tabor, where are you when we need you?

Lynda La Rocca grew up in a part of the country where cemetery residents were known to emerge on Election Day, but now lives and writes in Twin Lakes.