by George Sibley

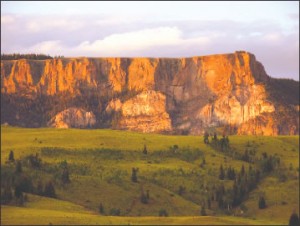

All the global “meltdowns,” economic and otherwise, have been temporarily, subtly trumped here by the onset of the annual local meltdown that signals “Springtime in the Rockies” – that interval of mud, gray skies, and soggy erratic weather during which, that old song notwithstanding, “I’ll be coming back to you” only if you happen to live in Cuernavaca, or at least Canon City, someplace without dirty snow. Nonetheless, even that onset of mud and sogginess generates an involuntary uptick in the human spirit, no matter what the news from the larger world.

But it is only early March as I write this! It’s not supposed to feel like spring this early – occasionally, maybe, but not every day. And the funny thing is, it felt like this most of February. We had a day of rain in Gunnison late in February, and all winter the temperature never got to twenty below.

Our unofficial Upper Gunnison weatherman Bruce Bartleson says that it has been an “average” winter in terms of snowfall, highs and lows and average temperatures, but it sure has felt mild. He says this is just a relative thing, compared to last year when we set multiple records for snowfall and cold days. But all of those records last year were set between December and mid-February – and last year by early March, it also felt like spring; the records shows that we went from record snowfalls in “high winter” to subnormal precipitation in late winter and spring.

This has happened enough over the past two decades so that one might observe that, while the substance of the winters might be “normal,” the “shape” of winter seems to be changing. By “shape,” I mean the way the winter unfolds, progresses, however one would say that. To give a gross unscientific generalization, big snows seem to be coming in the first half of the winter, and the back half of winter has been feeling like spring. Along the backbone of Central Colorado, twelve of our last fifteen Marches have had below normal snowfalls (water content). SNOpack TELemetry (SNOTEL) sites, run by the Natural Resources Conservation Service to measure snowfall, water content, temperature etc., show new record high temperatures for practically every day this March so far. To be sure, this could change overnight – but it will need to change a lot to be just get back to “average.”

This reinforces the larger observation that spring is coming earlier throughout the West; by a number of measurable criteria including bird arrivals, plants popping up, etc., it averages out to about a week earlier throughout the region since the 1970s. That’s what I mean by the changing “shape” of the winter. The statistics might tally out to be average, but this year, like last year, most of our snow came early in a huge December storm – more than 200 percent of the long term average last December, and close to that this year – then tailed off to subnormal snowfalls by late February and March (so far).

If you are getting your guard up on the assumption that I am about to go off about “global warming” – relax. I don’t really care whether you believe this early advance of spring is our fault or just natural cycling. What’s important down on the ground in Central Colorado is trying to figure out the consequences of whatever is changing the local weather. This is important because we are starting to perceive some mysteries in the processes that deliver the water we depend on.

Last year, for example, we had such a huge snowpack in the Upper Gunnison that there was serious concern about a huge runoff when the snow melted. The Bureau of Reclamation – loathe to let any water get past a dam without going through a turbine – drew down its reservoirs quite a bit to make room for the anticipated runoff. Everyone living in the floodplain laid in a lot of sandbags.

But the big runoff never materialized. The snow just sort of disappeared, and despite the record snow year, the reservoirs didn’t refill. So, what happened? One thing was (compared to long term records) the unusually warm late winter. Another thing was a cool spring (although that was pretty typical) – spring always seems to be full of surprises, and this year the surprise was a lot of coolth (yes, it is a real word), right into June.

The result of these two weather events – one unusual, one not so – was three relatively modest “peak flows” rather than one big one. The mostly-cool spring weather slowed the melt, and the assumption was that more of the water was able to soak into the ground– especially given that the previous fall was very dry.

But sitting in my home office here a few mornings ago, looking out the window when I should have been working, I hatched another, slightly more ominous hypothesis. I saw what appeared to be steam rising off the roof of our attached garage. Steam? When the temperature outside, despite a bright and warm morning sun, was still in the low 30s? I realized I was seeing wasn’t steam, but water going straight from its solid state (snow and ice) to its vaporous state without going through its liquid state. Sublimation, it’s called.

I checked in with weatherman Bartleson (a scientist by training); he concurred that that was what I was seeing, and referred me to a study of sublimation in the Yukon – the only study of sublimation we’ve managed to find. That study – high latitude, low altitude rather than the opposite – indicated that as much as one-third of the Arctic snowpack sublimated rather than melting. And it also suggested that the sublimation was greater before the real snowmelt started than it was when the temperatures got warm enough to really turn snow to water.

The implications for us locally? I’m not a scientist, so I can just hypothesize and hope a scientist will design a study that proves me wrong. But here’s my hypothesis: “unusually” warm Marches are not all that warm; they are still cooler than a cool May. But if we have three straight months of weather that is at first warm enough to sublimate snow to vapor – especially with a dry wind, relatively common on warm afternoons here – but then too cool to create a fast melt (but still warm enough to sublimate), then we are losing a lot of snow melt water to vapor that never enters our streams. Some of it might eventually condense out as precipitation somewhere else – but dammit, that’s our water!

Is this a significant factor in our water supply? Nobody knows, but we probably ought to try to find out. Right now, the Colorado Water Conservation Board is in conducting a big study of the Upper Colorado River region, trying to find out, practically to the gallon, whether or not the State of Colorado has any water left to develop – and what’s likely to happen to our Colorado River water under various climate-change scenarios. Since a consensus of climate scientists believe that the American Southwest will be generally warmer and drier in the future, with shorter winters, we had better hope that someone is designing a good sublimation study for Central Colorado’s headwaters snowpack that the whole Southwest and lower Midwest depends on for most of its water supply.

As Brad Udall from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder has often said, warmer temperatures alone are enough to reduce the water supply of the Southwest, even if precipitation levels don’t change. The Aspen Skiing Corporation is doing future planning on the assumption that they will no longer have skiing by 2050.

Of course, all of this forward thinking could be driven out of my under-disciplined mind overnight, by a three-foot snowstorm followed by a big Arctic front. But tonight, it just doesn’t feel like that’ll happen – and if it did, it wouldn’t really change the larger picture I’m describing.

Tonight, early in March, with the temperature at dusk in Gunnison still in the high thirties, it just feels like spring. And I’m going to go stand on the porch with the last of a glass of wine and toast the half moon ascending. When it’s springtime in the Rockies and the moon is ascending over Central Colorado, I’m not sure that I have really evolved far enough to take all this as seriously as it deserves. Tomorrow, sublimation. Tonight, just sublime.

George Sibley lives in Gunnison, so hasn’t put his snow shovel away just yet.