Column by Hal Walter

Agriculture – July 2006 – Colorado Central Magazine

WILLIE NELSON HAS SAID that farmers and ranchers are the backbone of our country. I happen to think he’s right.

Last month in this column I discussed the National Animal Identification System, what seems like an absurd blend of George Orwell’s “1984” and “Animal Farm” in which farms, ranches and livestock will be registered, and some animals will be outfitted with radio frequency identification devices.

In review, the stated purpose of the program is to protect us from alleged dangers such as Mad Cow disease, Foot and Mouth, bird flu and bioterrorism. Registration will be used to develop a National Animal Identification Database, available to animal health and public health officials in the event of a disease outbreak. The database supposedly would be privately managed and only available to government officials in the event of a disease outbreak or other emergency.

But then, we saw how that worked with our telephone-call records, didn’t we?

I later retooled the essay and it was published in The Pueblo Chieftain’s Sunday editorial section (some of that new information is contained within this column). Within a week of that piece being published, Colorado State Commissioner of Agriculture Don Ament replied in a guest column. Ament now holds the distinction of being the highest-level public official ever to respond to anything I’ve written.

Ament’s cordial rebuttal was interesting mainly in that it confirmed my main point — that this program is not some conspiracy theory dreamed up by paranoid small farm and ranch operators. It’s for real, and the government on both the state and federal levels intends to convince livestock owners to comply, whether they own one chicken, four burros or 1,000 cows.

Saying that I had “waxed nostalgic” with my notion that buying foods directly from local farmers is good regional economics as well as good nutrition, Ament made it clear the Colorado Department of Agriculture supports the NAIS, mainly from the standpoint of using it to track disease outbreaks.

He also noted, as did I, that Colorado already has a mandatory brand-inspection program, and thus many farms, ranches and livestock animals are already identified. In fact, all my burros have Colorado Brand Inspection cards, which I am required to have with me whenever I transport my animals more than 75 miles from the Out There Pack-Burro Ranchito.

Ament, however, seemed to miss my point that requiring those livestock operators who do not deal in the global industrial food complex to ID their animals is a waste of time, money and effort. For instance, if a farmer raises a pig that was born on his farm, takes the pig to a USDA-inspected butcher, then sells the meat to me, there’s really no need to track the animal. I know where the meat came from, and the farmer knows where the pig came from. Further, the animal is very unlikely to have a disease. It’s that simple. The pig really does not need an RFID tag stuck in its ear.

However, larger operators who deal with cattle and other livestock in sale barns and feedlots — animals that may someday be eaten by consumers in other countries such as Japan — may be another story altogether. I think it’s important to make the distinction between small family farm operations who deal directly with consumers and those who operate under the global factory farm model.

Ament did offer that perhaps there was room for compromise, saying the “NAIS is not a one-size-fits-all program, and how its end goals are achieved will differ from large to small operations, from species to species, and from one type of operation to another.”

However, provisions for individuality are not noted on the USDA’s NAIS website (www.usda.gov/nais/).

MY LOCAL VETERINARIAN, Scott Gillespie of Westcliffe, is a proponent of the national animal ID system. While he fully understands the hesitation of many independent farmers and ranchers to go along, he says the program makes sense in the face of global diseases and the threat of bioterrorism.

“My heart is with the small producer,” says Gillespie, who likens the program to buying insurance for his house. “We could go 100 years and not need the NAIS, but we do know there is a likelihood of an animal disease outbreak. From an animal health standpoint it really does make a lot of sense.”

Gillespie cites a recent experience in his practice as an example of how fast an animal — and potentially a disease — could travel. He was working some cows that had been delivered to a Wet Mountain Valley ranch and noticed a cow, which had been purchased in Oklahoma, was wearing a Louisiana eartag.

“So in a period of 72 hours that cow moved from somewhere in Louisiana and was in Custer County,” he says. “If that cow was carrying a disease, and didn’t have an ear tag, you wouldn’t know where she came from.”

Gillespie says the NAIS would be able to trace the cow back to her origins if she was found to have a disease. And while he does appreciate the concerns of farmers about privacy, costs and hassles, he notes that the figures he’s seen indicate a cost of $2 to $3 per head to put an RFID tag in a cow, and it’s his understanding that animals that don’t leave the premises would not have to be registered.

I buy my grass-fed beef, pasture-raised pork and fresh summer vegetables from Doug Wiley of Avondale. He often wears a ballcap that says “Grassfarmer” because his pastures are the center of his livestock operation. The idea of an animal ID system is particularly troublesome to him because he does not deal in the global livestock market. He simply raises livestock and sells the meat locally.

Wiley says states already have protocols in place to handle disease outbreaks, and that the program amounts to licensing farmers.

“Virtually it’s a license to own livestock — if you don’t register with the government you can’t own livestock anymore,” Wiley says. “Why don’t they just tag the farmer while they’re at it? How far are we away from that?”

Moreover, Wiley says that an ounce of prevention may be worth 50 pounds of backtracking.

“It’s a proven fact these diseases are preventable through sound animal husbandry and complete mineral nutrition,” Wiley says. “The most cost-effective way to prevent the spread of disease would be to help producers strengthen the natural immunity of their herds.”

WILEY ALSO QUESTIONS the notion of the government overseeing the type of bureaucracy that would be necessary to administer such a program, and what the costs and documentation requirements eventually would be to smaller livestock growers.

“You develop a bureaucracy to administer this, and once it is in place we’re stuck with the cost,” he says. “When have you ever heard of a government program that ends up costing what they said it would?”

He fears farmers would be stuck with that burden. “As typical food producers, we can’t pass on that cost.”

In the case of animals like hogs and chickens, Wiley says the per-head cost of such a program potentially could drive up his costs, and push the limits of what his customers will pay. “We are all being forced to share the costs of protecting export markets even if we don’t benefit from them.”

In my view, the communal benefits of supporting local agriculture range from the pragmatic notion of helping to keep our water out of the hands of developers, to the more abstract sentiment that the rural, agricultural lifestyle is a piece of our Western culture worth saving.

TO ME IT SEEMS almost unfathomable — even absurd — that the government would attempt to keep track of the daily comings, goings and whereabouts of every single farm critter. We have enough trouble keeping an honest list of registered voters.

And then there’s the expense. Whether borne by farmers, taxpayers, consumers or some combination thereof, the price of such a program could easily be in the billions. With cattle alone numbering upwards of 100 million head nationwide, it could cost nearly a quarter-billion dollars just to tag each bovine. Throw in machinery to read the tags, and other costs of such a bureaucracy — then multiply by at least a half-dozen other classes of livestock — and the pricetag seems out of reach for a country already deeply in debt.

One thing that’s clear is that we are not going to get to the bottom of this particular 50-pound bag of fertilizer any time soon. My intent is rather to use it to raise awareness and grow a debate on the matter.

Hopefully out of this debate the NAIS can be shaped to provide protections needed by large agribusiness to compete in the global marketplace, without placing unreasonable requirements and burdens on small farming operations, hobby farms and others who could be pinched by the burden of registration and compliance.

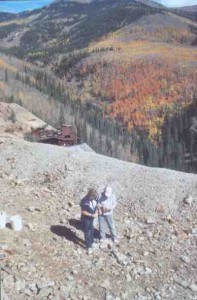

Hal Walter raises burros and cultivates prose near the ghost town of Ilse in the Wet Mountains.

The articles mentioned here are on the Net at Hal’s piece and Anent’s response. (Please note that they were there when this page was posted. They may not always be available.)