Article by Clint Driscoll

Agriculture – May 2004 – Colorado Central Magazine

DECEMBER 23, 2003 was not a day U.S. cattle producers will remember fondly. On that date the USDA announced a dairy cow in Washington state had been found to have Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy, more commonly known as Mad Cow Disease. BSE is a fatal wasting disease affecting the brain and central nervous system in cattle. It destroyed the British cattle herd beginning in the mid-eighties and peaked in 1993 when 1000 cases a week were reported. There is no cure.

According to a January 14, 2003 Denver Post article referencing the USHHS and USFDA, most authorities agree BSE is spread by the feeding of contaminated beef bone meal and rendered beef carcass remains to the next generation of calves raised for dairy or meat production. The cause of BSE is thought to be a malformed prion, a protein which makes up part of the neural cell surface. Since prions are not organisms, they cannot be eradicated in the same manner as bacteria or viruses. The prions are found in the brain, spinal cord, paraspinal ganglia (collections of nerve cell bodies and their fibers laying alongside the spine), tonsils, small intestine and retinas.

According to the Coleman Natural Beef website, prions are not found in muscle mass nor does there seem to be a horizontal spread from cow to cow. Milk and dairy products are not affected. BSE is slow acting, generally not producing overt symptoms until the animal is an adult, 24 to 30 months or older.

BSE would be an agricultural disaster even if it only affected cattle but there is believed to be a link to a human disease called variant Creutzfeld-Jakob Disease (vCJD), another fatal neural and brain wasting disease. The most common cause of vCJD is the inclusion of infected animal neural tissue in ground or processed meats intended for human consumption and bone-in cuts from the spinal area which may inadvertently include paraspinal nerve tissue. There are no documented cases of vCJD in the U.S. caused by domestic beef but over 120 vCJD deaths have occurred in Britain since the BSE outbreak there.

THE BSE discovery in Washington and the subsequent publication of information on the use of ground bone and rendered carcass meal (banned in cattle feed since August 4, 1997 but still allowed in poultry and pork feed and pet food) and even blood from slaughtered cattle used to feed unweaned dairy calves (recently banned) has given health-conscious meat eaters heightened interest in alternatives to traditionally raised and processed beef.

Many have turned to “natural” beef but according to Ellen Sweets in her above-referenced Denver Post article, the USDA natural label means very little. As far as the USDA is concerned, “natural” means only that the meat has been minimally processed and contains no artificial preservatives or ingredients. Almost any fresh beef falls under that definition. What is not referenced are the raising practices prior to slaughter including what was fed to the animal or what steroids or antibiotics were used.

Serious natural beef producers such as Coleman or Maverick Ranch among others have set their own verifiable standards which guarantee their cattle are fed an antibiotic/hormone-free vegetarian diet and can trace their beef from birth to processing. For organic purists, the all-vegetarian diet is organically grown, but in this case the USDA has set such stringent standards for the organic label most producers do not put up with the bureaucratic hassle of using the label even if they practice organic methods.

An important point to note about natural or organic in the labeling is that the cattle can be fed grains such as corn, something that was never in the original diet of cattle. Those interested in grain-free meat can consider grass-fed products. Grass-fed means the animals were raised entirely on pasturage or hay, with no grains ever included in their diet.

FOR CONSUMERS IN Central Colorado who want to try beef from non-traditional, local producers there are options.

The Oswald Cattle Company, operated by Steve and Nancy Oswald, raises grass-fed beef which is marketed under their Backcountry Beef label.

The Oswald Ranch, which has been in Nancy’s family for over 50 years, comprises 2700 acres plus BLM and private land leases located between Cotopaxi and Westcliffe. Steve began learning traditional ranching basics in the Cotopaxi area where he met Nancy in the early 1970s. He followed his employer to Williams Lake, British Columbia and from there to Canada’s Gang Ranch, at one time the largest ranching concern in North America. While Nancy taught school and wrote a novel subsequently published in Canada, Steve worked his way up to farm manager responsible for all pasture, hay and broadleaf legume production on the huge ranch. He became an expert in grass-farming basics including fencing, irrigation, feed harvesting and storage.

Byron and Shelly Shelton provide grass-fed Landmark Harvest beef through their Landmark Diversified operation.

Byron Shelton is a fourth-generation Colorado rancher who grew up working on family ranches with his cousins on the eastern plains. He graduated from CSU with a degree in Agricultural Economics and has taught vocational agricultural education in high schools and Natural Resource Economics at Colorado Mountain College. He attended the Savory Center for Holistic Management in Albuquerque in 1987 and now teaches and acts as a consultant on ranch and rangeland management for the Savory Center.

He and Shelly, who grew up farming in Iowa, have been ranch managers on working ranches, dude ranches and large mountain youth camps such as the sprawling Adventures Unlimited camp in northern Chaffee County. They live near Buena Vista and lease and manage private land for their Landmark operations.

Both the Oswalds and the Sheltons employ Holistic Resource Management techniques on their lands. The system was promoted by Allan Savory and made familiar in this region in Sam Bingham’s book The Last Ranch. Basically Savory advocates intensive grazing of selected pasture, allowing the fenced plots to be thoroughly trampled then the herd is rotated to new pasture, thereby giving the land time to recover. The system mimics the way wild grazing herds act in a symbiotic relationship with the whole land/plant/watershed system.

IN SIMPLIFIED TERMS, soil left undisturbed tends to crust over which prevents precipitation from seeping in, replenishing groundwater and vitalizing the plants. Much of the water simply runs off and evaporates. Eventually grasses die off and deserts form. When grazing herds move through, the soil crust is broken by their hooves and enriched by their manure and the plants get eaten down as they move over the range. In pre-settlement times the herds were kept bunched and moving by their need to find water — and by predators. In modern times domestic herds take the place of wild herds and humans take the place of the predators purposely moving the herd from pasture to pasture.

For Byron and Shelly their Landmark cattle are a by-product of their primary business. The cattle are one of many HRM tools they use for managing farms and ranches ecologically and economically and for facilitating and training others in ecosystem processes and grazing and land planning. They know HRM techniques apply not only to agriculture but to every aspect of land use.

“What happens on the land determines the watershed,” explained Byron. “It can only function with healthy plants, natural water flow (above and below the surface) and prevention of soil crusting. That’s why we deal not only with ranchers but also developers and ranchette owners.”

For the Oswalds, the cattle are not a by-product of restoration but the reason for the land restoration. When they returned to the ranch in 1991 it had been leased for several years and was “pretty beat up” in Steve’s words. Steve and Nancy set to work using HRM techniques to restore the pastures. Their long-range business plan was to build a herd of about 200 head and market grass-fed beef in the immediate region. The drought of 2002 set them back, they had to sell off about two-thirds of the herd but they are rebuilding and the land is recovering. They employ not only Savory’s techniques but also those of Stan Parsons whose Ranching for Profit program expands on the HRM philosophy.

“Can you imagine?” said Steve, “A rancher actually working to make a profit? The whole point is, you can be the best ecologist in the world but if you’re going broke, so what?”

Grass-fed beef are not raised in the traditional manner. The traditional practice requires that calves be dropped in late winter or early spring. The cow-calf pairs are moved to pasture for spring and summer and the cow is bred again in August or September. The herd is brought down in the fall. The rancher can choose to continue to feed the calves (now separated from the cows) or sell them as “stockers” to another rancher. That rancher then continues the stockers on grass and hay through the winter and the following summer. They are then sold as “feeders.” At this point they are shipped to feed lots where their natural diet is changed. They are fattened on grain (mixed with other products such as past-sell-by dated bread, pastries and snack products) and given steroids to increase growth. They are also given antibiotics to prevent infections and diseases caused by the confined quarters of the manure filled lots.

GRASS-FED MANAGEMENT means calving takes place in summer. Calves are weaned in January and run as yearlings. Males are not castrated at birth or soon after, but in about a year. This allows naturally produced testosterone to promote development rather than artificial steroids. Grass-fed cattle are not “finished” or ready for market for about 30 months. During that time, the Oswald and Shelton herds are moved under careful rotation schedules from pasture to pasture, feeding on the available grasses, alfalfa and clovers. “Basically we’re involved in solar harvesting,” said Steve, “All that energy is building our beef through the plants. Best of all that energy is free — just about the only free thing in this world.”

HRM pastures produce tall grasses easily found by cattle even in winter. Not only do the Sheltons and Oswalds not need grain production equipment, they also have no haying equipment. Snow layers are generally not deep in the upper Arkansas valley which means cutting and putting up hay is not necessary.

“It’s not often the snows are so deep the cattle can’t get to grass. When it does happen I can buy good grass hay. It’s still less expensive than putting all that time into irrigating, cutting, baling and stacking. I figure I save about $5000 a year just in labor costs, not counting savings on fuel and equipment upkeep,” said Steve.

Of course not all land contains perfect pastures. About half the Oswald ranch consists of Scrub Oak, Mountain Mahogany, and other plants cattle won’t eat including the noxious Knapweed.

“Before I took Parson’s seminar I was really trying to eradicate the Knapweed and that included spraying,” said Steve. But HRM and Ranching for Profit advises the landowner to ask what the end-goal is, what is desired rather than what is not desired. In this case, it seemed best not to spend money and potentially harm the land by killing Knapweed. Instead, the goal was to enhance the land.

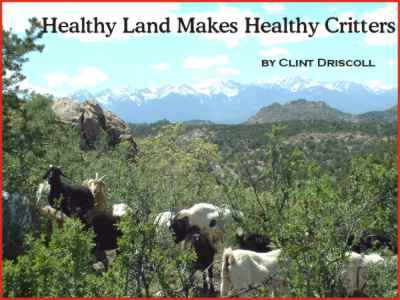

ALSO, IF CATTLE wouldn’t utilize all of the available forage, it made sense to find something that would. To that end the Oswalds are experimenting with goats. By June the Oswalds will be running about 1500 head of Spanish-Cashmere nannies cross-bred with Boer billies. Steve and Nancy are raising them for the growing ethnic market and using them to clear choked bottom land and to control Knapweed and trim out oak and mahogany.

The grazing techniques are the same but according to Nancy the goats are much more precocious than cattle and can wander further and faster. They use four-strand portable electric fence to keep them in selected areas rather than the simple one-strand used for cattle. The herd is also protected from most predators by six huge Anatolian-Grand Pyrenees guard dogs.

Both producers agree that grass-fed products are a niche market. But there is a growing hunger for grass-fed meat. A finished grass-fed animal is quite different from the traditionally finished animal. According to the Eat Wild website pasture-raised meat has more Omega-3 fatty acids, Vitamin E and Beta Carotene than traditional beef. There is less total fat and Omega-6, which has been linked to a number of disorders, and the meat also has two to five times more conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a newly recognized cancer-fighting fat.

Because it is quite lean, the meat tastes somewhat different, but most people who try it like it; older customers say it tastes like the meat they ate when they were children. And grass-fed meat requires less cooking than regular beef which means nutrients are not destroyed by too much heat.

Steve intends his market demographic to be primarily the boomers who are beginning to retire to the area. They are concerned about their health and the environment and have enough money to pay for quality products.

Both outfits plan to stay regional. Backcountry Beef is sold in one natural food store in Colorado Springs or directly to individuals through Backcountrybeef.com. Landmark Harvest can be found in Buena Vista at Nature’s Pantry and in Salida at Simple Foods and Sunshine Market, or it can be special ordered.

“There are co-ops out there, mostly for those who only want to raise beef and allow someone else to process and market it, but I don’t want to sell my soul to an organization. This is our product, we’re proud of it and we’ll raise and market it,” said Steve.

THE SHELTONS AND OSWALDS believe that their best advertising is their production method. They guarantee all calves are born at home, raised in pastures that are not treated with chemical fertilizers, pesticides or herbicides and processed locally. Both use the USDA inspected Scanga processing facility in Salida. They want their customers to know them and know where their food is coming from. They know the end goal is not only to provide a premium product but to help determine what the watershed should look like and how it should function to provide that product.

“We’re working in a way that’s beyond organic,” said Byron, “Where BSE is not even an issue.”

The Oswalds can be contacted at: Oswald Cattle Company, P.O. Box 304, Cotopaxi, CO 81223, 719-942-4361, steveo@bwn.net, www.backcountrybeef.com

The Sheltons can be contacted at: Landmark Diversified, 33900 Surrey Lane, Buena Vista, CO 81211, 719-395-8157. landmark@my.amigo.net

Clint Driscoll lives and eats in Buena Vista. He’d rather have a dish of curried goat and rice than a T-Bone any day but believes it’s great he can get both in Central Colorado.