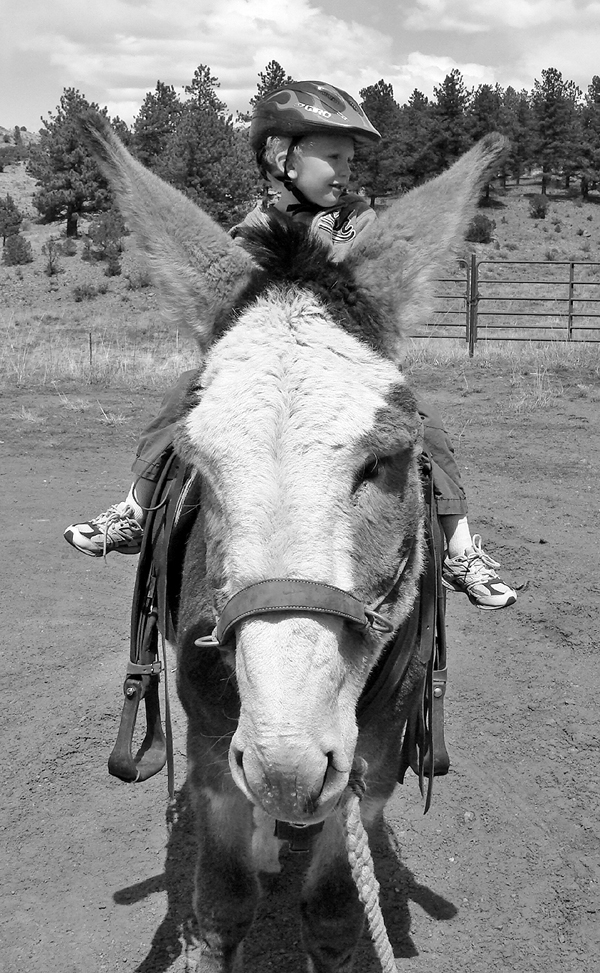

Long before I learned my son Harrison has autism, or what the word “hippotherapy” means, I had this idea he should ride our burros. For me this was a way to incorporate fatherhood into my lifestyle.

For three decades I have trained burros for pack-burro racing, including six world championships, as well as for packing and riding. It seemed only natural I would want to share that with my son, and it would also help provide a vehicle to the backcountry.

In the beginning it was just short rides. But we were building toward something bigger, and in the late summer of Harrison’s third year we took a three-day trip over Music Pass in the Sangre de Cristo range with Harrison riding our smallest burro Spike, and our biggest burro Redbo packing our gear. I later wondered if taking a three-year-old over a high mountain pass on a burro was such a smart idea.

In his fourth year, when Harrison was officially diagnosed, we didn’t manage an overnight pack trip but continued with regular trail rides on neighboring Bear Basin Ranch. Shortly after Harrison’s 5th birthday I read a story about a man who used therapeutic recreational riding to help his autistic son. Rupert Isaacson wrote a book called “The Horse Boy” about the experience.

Reading this piece renewed my interest in Harrison’s riding, and the use of donkeys in this type of therapy. Perhaps one piece to this autism puzzle had been right here under my nose all along. Donkeys seem well suited to this task since their movement is virtually the same as a horse, yet their generally calmer nature makes them less scary.

There is a difference between therapeutic recreational riding and hippotherapy, which is done under the guidance of a licensed therapist (speech, occupational, physical, psychologist, etc.). But we don’t need no stinking badges — as Harrison rides we often sing and recite books.

We try to get him out riding fairly regularly when the weather is nice. Harrison is prone to screaming and tantrums. But on the days he rides, and even on days following a ride, we’ve noticed marked improvement in his disposition and behavior. This activity is also therapeutic for parents — actively engaging the child in an enjoyable activity while freeing yourself to walk and enjoy the outdoors. We lead the donkey from the ground and keep a watchful eye out for any safety issues, such as wildlife, horses, or my own dog crashing out of the brush.

This past summer we made an effort to get out even more, combining riding excursions with fishing expeditions in the Sangre de Cristos and the Wet Mountains. These treks reopened the world I knew so well before Harrison was born. The rolling stretches of trail, the flash of trout, the aspen glades and the old spruce-fir forests all came rushing back into my consciousness. It was all still there for me to relearn and for Harrison to experience for the first time.

There were trips to the Swift Creek beaver ponds, where Harrison caught his first fish, and to Goodwin beaver ponds, where we realized we had left a segment of the flyrod back at home.

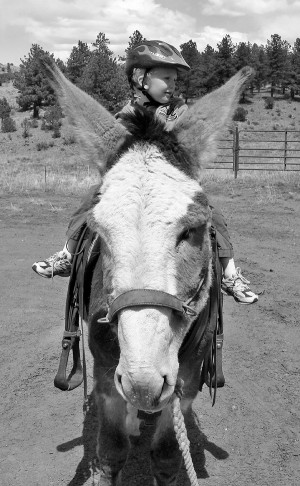

We took a much longer excursion into the Macy Lake drainage. But the high point of the summer was when Harrison rode Redbo to Horn Lake and back, 11 miles and 6.5 hours total. I was totally amazed at how my son rode that steep, rocky, slippery trail, and also how well Redbo took care of him even when we were caught in an icy downpour of rain and hail on the way out.

As the school year began, the days grew shorter and the weather turned cold. Riding became been less frequent, and it seemed like Harrison’s behavioral issues were increasing. A neighbor loaned me a copy of “The Horse Boy” and I found the story intriguing in light of what I had learned through Harrison’s riding.

Isaacson discovered his son Rowan to have connections to the world of shamanism and also to horses. So he took him to a place where both are still an integral part of life — the backcountry of Mongolia. The resulting story is one of courage and triumph.

The book was compelling on many levels. For starters, the story is an epic real-life adventure. However, what struck home for me was Isaacson’s familiar description of his son’s speech habits, peculiarities of behavior, screaming and tantrums. Most valuable was the manner in which this father openly discusses his very personal feelings about his son’s condition, and the impact it has had on every part of his life, including his own physical and mental well-being, his work and his marriage.

It seemed the only place anything could go right was on the back of a horse, though Isaacson also describes some scary experiences that seem to come with the territory when dealing with equines.

I suppose I too should have been expecting a setback, and one day it happened. We were watching the 4-H kids practice equine drills in the arena at the ranch I manage. Harrison was on Spike, and I was on foot and had the lead rope. Harrison had been protesting his helmet. He cantankerously removed it and dropped it to the ground next to Spike. The burro didn’t flinch.

I picked up the helmet and just a few moments later glanced at Spike and saw something very wrong going on in his eyes. To this day I still have no idea what spooked him. What happened next unraveled so fast it took me days to piece it all back together.

Suddenly Spike backed, spun and took off bucking. The next thing I knew I was sprinting down an embankment, “climbing” the lead rope hand-over-hand as I ran trying to gain control of the berserk burro, who was running away with my son.

At some point I knew I had to somehow get a grip on Harrison and pull him out of the saddle before the whole rodeo got away from me. But this would require letting go of the rope. I remember getting my left arm around Harrison and pulling him off Spike just as I let go of the rope and lost my footing. For what seemed like forever, I wrestled horizontally in mid-air, flying, twisting and contorting in an attempt to hit the ground first and break Harrison’s fall.

We landed in some shallow snow, and miraculously nobody was seriously hurt, though Harrison apparently bit his cheek, and I felt pretty beat up both physically and mentally.

I held the screaming boy tightly and offered up a prayer of thanks that he was OK.

All the magic of the connection between animal and child can come undone in only a few seconds. And then the second-guessing sets in: Is this riding thing really helpful, or is it merely my ego at work? Is it just too dangerous?

Spike should be a “dead-broke” burro, but what he did bordered on psycho. I doubt I’ll ever let Harrison ride him again.

Harrison did, however, get back on a different burro the next day, riding Redbo for a short ways. There was no problem with him keeping the helmet on.

“Spike is bad behavior,” he said from the saddle. “Redbo is better.”

I was reminded of my first horseback riding experience when I was about Harrison’s age. A Shetland pony ran off with me at my great uncle Glen’s farm in Missouri. I have a dim memory of the pony running fast across a pasture and stopping short of a fence. Somehow I stayed on. When I visited the farm shortly before Glen’s death in 1997 none of the landscape seemed familiar, but that ride remains etched in my mind.

I’m sure Harrison will never forget his rodeo ride on Spike. But my scary ride didn’t break me of my passion for animals and the outdoors. And I doubt his will either. This is the new frontier, and we’re in this together, for the long haul.

Hal Walter writes and edits from the Wet Mountains. You can keep up with him regularly at his blog: www.hardscrabbletimes.com