Review by Ed Quillen

Climate – November 2004 – Colorado Central Magazine

Floods, Famines, and Emperors – El Niño and the Fate of Civilizations

by Brian Fagan

Published in 1999 by Basic Books

ISBN 0-465-01121-7

THIS TIME OF YEAR, especially during a multi-year drought, you may hear quite a bit about “an El Niño year” and how that might ease our water shortages. Indeed, the climatologists are now speculating that El Niño might arrive this winter, with consequent improvements for our snowpacks.

If you’ve ever wondered what they’re talking about, this book is a good place to get some answers.

In literal Spanish, “El Niño” means “the [male] child.” The term got applied to weather on the arid west coast of Peru, where the Pacific coastal waters are usually cold. But every so often, the water gets warmer — anchovies are replaced by tropical fish, millions of birds change their flight routes, torrential rains come inland.

When this happens, it occurs around Christmas — the birthday of “the child” or “El Niño.”

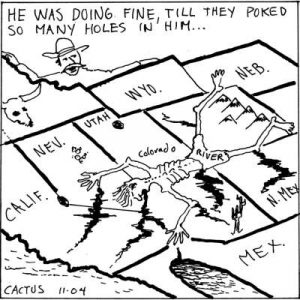

But the Peruvian coast is only a small part of the story that scientists call ENSO for El Niño Seasonal Oscillation. Solar heat builds a pool of warm water in the Pacific Ocean. Normally, the pool drifts west. But some years, it builds and then moves east to strike the Americas. The California coastline gets hammered and clifftop houses slide into the ocean. In the Rockies, we get abundant winter snow and a wet spring. Elsewhere in an El Niño year, Africa suffers from drought, the monsoons fail to arrive in India, and Indonesia goes dry with immense forest fires.

IN FLOODS, FAMINES, AND EMPERORS, Brian Fagan explains this quite clearly, along with a possibly related, and perhaps even more powerful phenomenon known as the North Atlantic Oscillation. Sea-water temperatures determine ocean currents which are reflected in air currents and clouds that become our weather hundreds of miles from any ocean.

“With the sudden influx of heat in the eastern Pacific [from the pool of warm water moving east to the Americas], the vast reservoir of warm, moist air over South America bulges dramatically, then cascades outward, disrupting the vast air flows that circle the earth. The jet streams lurch north, bringing heavy rains and severe storms to Mexico, California, even the Pacific Northwest. Then the same stream crosses the Rocky Mountains, keeping arctic air from the far north out of the United States, so that Chicago and New York enjoy unusually mild, wet winters. Strong easterlies blow in the Caribbean, while displaced jet stream effects bring storms to the Gulf of Mexico and an abnormally cool winter to the South…. Australian sheep farmers suffer through months of parching drought. Huge forest fires mantle much of Indonesia in suffocating smoke and grime, as they did in 1983 and 1997…. Meanwhile, the Christmas Child creates havoc far downwind, eventually influencing weather in Africa, the North Atlant

Fagan explains not only the effects of ENSO, but how scientists connected the experiences of Peruvian coastal residents with wide-spread temperature and other observations to derive the connections.

That’s the first third of the book. The rest contains the history, much of it based on speculation, of civilizations and cultures which ran afoul of the weather. Many overbuilt during good times, and thus lacked the capacity to endure during hard times — like the Mayans and the Moche. Others did manage; the Egyptians adjusted their government, and the Anasazi moved from the Four Corners to the upper Rio Grande.

To his credit, Fagan addresses global warming, but concedes that we still don’t know some important facts. Are the rising temperatures part of a long-term trend? Or are they just part of the normal variation in the earth’s climate that has brought us Ice Ages in the past? And are industrial “greenhouse gases” like CO2 a significant factor when a single volcano can spew out so much?

DESPITE ITS SUBTITLE, this book goes far beyond El Niño in its examination of the interaction between climate variations and human culture. That extended stuff is good reading, even if much of it is based on speculation, because Fagan is an engaging writer.

But the real strength of this volume is in the first four chapters, where Fagan describes the ENSO, gives a history of its discovery, and explains how it is monitored.

As the saying goes, “Everybody talks about the weather, but nobody does anything about it.” This book won’t change that, but it will help you understand all of the talk about whether this will be an El Niño winter or not. — Ed Quillen