The Strange Case of Capt. E. Wayne Eaton

Part One

By Charles F. Price

The first and surest consequence of any calamity is the laying of blame. Whatever the disaster, natural or human, someone must pay for letting it happen. The worse the event, the more urgent the need to find and punish a party who can plausibly be held responsible. And if an actual culprit can’t be exposed, and if those in power fear they may be seen as accountable, a scapegoat will always do.

That’s what happened to Capt. Ethan Wayne Eaton in the wake of the worst outbreak of lawlessness in the young history of Colorado Territory, the 1863 murder raid of the Espinosas, the brothers Felipe and Vivián and their nephew José Vincente. The Espinosas killed their first victim in Eaton’s military jurisdiction, then went on to murder ten more men elsewhere in Colorado. What makes Eaton’s case intriguing is how the scapegoating over the Espinosas quickly deteriorated into a savage squabble among army officers about niceties of military etiquette, diverting attentions from the outlaws while they continued their atrocities elsewhere, to be pursued and eventually dispatched by others.

Now largely forgotten, Eaton was a figure of some note in his era. But three of the most considerable figures in the annals of the Southwest, two of whom shared some blame for the Espinosas’ breakout, pointed accusing fingers at him. And Eaton, however well regarded, was a small fry compared to the trio of titans who set out to crush him.

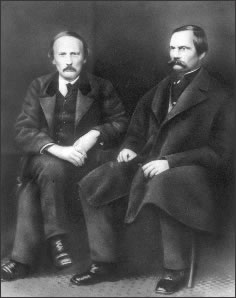

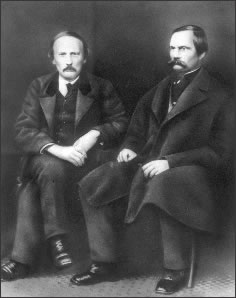

One was Brig. Gen. James H. Carleton, virtual dictator of the New Mexico Territory during the Civil War, remembered even today for his ruthlessness, his towering but flawed intellect, and his most tragic miscalculation, the persecution of the Navajo. The other was feral Colonel John M. Chivington, commander of the First Colorado Volunteers, hero of the battle of Glorieta Pass, minister and presiding elder of the Rocky Mountain Conference of Methodist Church and, later, unapologetic perpetrator of the infamous Sand Creek massacre of Cheyenne Indians. The third was Maj. Archibald H. Gillespie, one of the greatest heroes of the American conquest of the Southwest. His memory has now been eclipsed by time, but in 1863 he was still a living legend, having played a vital if somewhat mysterious role in the wresting of California from Mexico.

Carleton and Gillespie tried to disgrace Eaton, a junior officer who they agreed lacked the fortitude and influence to fight back; Chivington enabled them. The story of Eaton’s struggle to redeem his good name and defend his own acts against such mighty adversaries has never been fully told until now—a tale all the more remarkable because the acts he defended were genuinely questionable.

A New York native, Eaton came to New Mexico in 1849 to prospect for gold. In 1851, with a partner, he bought an immense land grant in the Galisteo Basin. Afterwards he acquired the partner’s share and became a prominent rancher. He married an Hispanic woman, learned to speak and write fluent Spanish, and, unlike many Anglos, fitted comfortably into the easygoing culture of Nuevo Mexico.

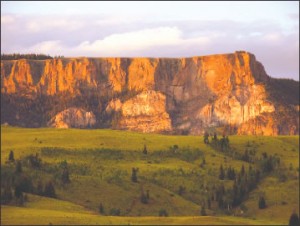

When the Civil War began he raised a company of volunteer infantry, serving during the 1862 Confederate invasion of the territory as commander of Fort Craig. After the Rebels were defeated, Eaton and his Company D, First New Mexico Volunteer Cavalry, were transferred to Fort Garland in the San Luis Valley, then under the command of Major A. H. Mayer.

Since the outbreak of war, the San Luis Valley operations, despite its location in southern Colorado, had been part of Carleton’s Military Department of New Mexico. But on November 9, 1862 the area had been transferred by General Order No. 11, Department of Missouri, from Carleton’s bailiwick to that of the District of Colorado. Col. Chivington in Denver became Garland’s new superior, publishing his takeover orders on November 15.

Confusion ensued. Major Mayer received orders late in November to begin reporting to Denver. Until then, an observer wrote, “no officer in Mexico (sic) or Colorado claimed that the post belonged to Colorado . . .” Accordingly Mayer forwarded the papers to Carleton. Immediately afterward, Mayer was transferred and on December 10, 1862 Eaton assumed command, inheriting the jurisdictional tangle. Soon he too got orders implying he should report to Denver. Like Mayer before him, he forwarded the papers to Carleton in Santa Fe. This time Carleton told him to obey the orders of Chivington and said the garrison of Fort Garland was to be dropped from the strength of the Department of New Mexico.

Nonetheless, after this time Carleton inexplicably continued to issue some orders direct to Eaton, as if Garland and the San Luis still belonged under him. It may be that Carleton justified himself with a loose interpretation of the wording of Government Order (G.O.) 11, which permitted “commanders in the field” to “cross lines and co-operate with adjacent commanders, when the interests of the department require it.” He also may have felt entitled to continue issuing orders to Garland since it was garrisoned by New Mexico Volunteers. Even more likely, he was obeying his natural instincts for absolute control. Since taking command he had held New Mexico in the iron grip of martial law, and though Colorado was now technically free of that restraint, he still insisted on enforcing certain rules of his choosing, such as requiring military passes for civilian travelers in the San Luis.

Worse complications were in store. At least two months before the transfer of jurisdiction, Carleton had given Maj. Gillespie a special assignment to undertake a “military census” of the largely Hispanic population in the San Luis Valley. But Gillespie was not recalled when the jurisdictional transfer under G.O. 11 went into effect, nor does the record show any effort by Carleton to advise Chivington of the census, much less seek his approval and supervision of it. Gillespie was in the field, using Fort Garland as his base of operations, actively conducting this census during October and November even as Denver editorialists were complaining that “our civil allegiance is due to Colorado, while being attached to the military department of New Mexico,” with the result that “the interests of this part of the country are . . . overlooked.”

Colorado was planning to impose territorial taxes for the first time, and the Denver press was reporting “the Mexicans of Costilla and Conejos Counties are holding secret meetings for an armed resistance.” One bulletin said “some of them have sworn to pay their taxes with the rifle.” Word that the New Mexico legislature was considering emancipation of Indian slaves had spilled over the border to enrage the Hispanics in the San Luis who had long practiced Indian servitude. There were rumors of a second Confederate invasion by the hated Texans who had been turned back the previous year; and Carleton’s census, which required an enrollment of all males between the ages of 18 and 45, excited fears of compulsory service and worries of military dictatorship, and seemed to revive resentments left over from the Anglo conquest of New Mexico in 1847.

In vain Gillespie tried to reassure the inhabitants that the census was only meant to gather information about the population and resources of the San Luis so that Carleton’s could “extend his care thus far, to protect their lives and property from an invading foe and the depredatory Indians, so as to secure their welfare.”

But while traveling in the area, Gillespie complained to Carleton that “most of the young men, or those liable to bear arms, had fled to the mountains from fear of being dragged away to fill the ranks of the Army.” One of the placitas the major visited was San Rafael (now Paisaje), home of the Espinosas. And if Gillespie is correct in his claim to have investigated every household in the Conejos, then he certainly entered—and, in their view, violated—the abode of the dreaded Felipe and Vivián Espinosa. Their male relatives, if not the outlaws themselves, were almost certainly among those avoiding the enrollment.

Adding to the volatility of the region, a Rebel guerrilla band under a Capt. George T. Madison was raiding in the area stealing cattle and robbing mail riders, and the Espinosas themselves were suspected of holding up a government wagon train near Fort Union. Gillespie reported that “a spirit of lawless recklessness” pervaded the whole valley, which he said was filled with “renegade Peons from New Mexico…disaffected, disloyal wretches, who are ever more ready to kill and rob an inoffensive, unarmed white, than the worst Indians of the most hostile tribes.”

Gillespie returned to Fort Garland on December 1, 1863. Fatigued by the “great amount of labor, vexation and annoyance” of his Conejos census, he nevertheless immediately commenced a similar survey of the area around Garland. He was engaged in that task when, on New Year’s Eve 1863, Capt. Eaton, Garland’s brand-new commander, ran afoul of one of his officers, 1st Lt. John Lewis.

At this time the Espinosas burst into Eaton’s life. In mid-December 1862 near Galisteo, Felipe and Vivián, “desperate and lawless bravos, known over the entire country,” robbed and assaulted a teamster. The teamster recognized them as neighbors from San Rafael. Eaton and Lt. Hodt had already, between September and December, led numerous patrols in the same area, seeking to quiet disturbances. On one foray, solicited by a deputy U.S. marshal named Austin, Lt. Hodt had arrested a troublemaker, Francisco Gallegos, who was making inflammatory speeches that “the laws ought not to be enforced and shall not be.” Hodt fetched Gallegos back to Garland; but somehow he managed to escape.

Now, on January 9, Carleton ordered Eaton to send a detachment of ten men back into the hotbed of San Rafael to arrest the Espinosas for their robbery of the teamster. On January 16 the detail, again under Lt. Hodt, made the arrest. Hodt locked the two Espinosas in a room of their house while he went in search of other persons suspected of lawbreaking. However, the Espinosas broke through a partition, armed themselves with “guns, pistols and bows and arrows” and “started firing the arrows through doors and windows.”

Hodt ordered the house set afire hoping to force the brothers into the open but when they came out, they did so in a rush “discharging a shower of arrows.” The troopers scattered and Hodt fired all the rounds of one revolver at them, to no effect, and drew a second pistol, which then failed to cock. When he tossed the balky weapon aside, its hammer hit the ground first and the gun fired, the ball striking the lieutenant in the forehead, inflicting a serious wound. The Espinosas fled toward the trees along the Conejos River. Deputy Austin gave chase on horseback but his mount lost its footing on the icy ground, fell on him and broke his leg. The fleeing outlaws fired at their remaining pursuers and killed a corporal. They managed to cross the river and withdraw safely into the San Juan Mountains, where they would remain in hiding for two months.

Carleton, enraged by the failure of the arrest mission, sent Eaton a blistering message on February 3 asserting “Lt. Hodt’s management was not satisfactory and it was doubtful if he had not mistaken his profession.” The general seems to have had a point; the hapless Hodt would die three years later as the result of “accidental discharge of his pistol.” Carleton grimly ordered Eaton to “personally attend to the capturing of the robbers…dead or alive.” It was clear he meant to lay the blame for the botched arrest attempt on the captain’s doorstep. What he didn’t consider was the possibility that in ordering Gillespie to perform a military census in the restive Conejos, an area he no longer commanded, he himself may have created conditions in which outlaws like the Espinosas could flourish.

Gillespie had written Carleton on January 20 that the “open deadly resistance to officers of the United States and the Civil Authorities of Colorado Territory” by the Espinosas proved what he had been saying about the disloyalty and lawlessness of the people in the San Luis. He believed “the strong arm of military power” needed to be used to “pursue and destroy” such troublemakers “without delay.” Still based at Garland conducting his census, Gillespie also decided to take upon himself the job of straightening up certain defects he saw in the management of the fort. Already, in a report to Carleton in December, he had darkly hinted at “the condition of affairs at this distant post, seriously affecting the discipline of the troops” and “occurrences at this Garrison, such as I have never witnessed before, in a long military experience.”

His experience was long indeed, and impressive. With the possible exception of John Charles Frémont and Stephen Watts Kearney, no officer had emerged from the Mexican War on brighter clouds of glory. As a Marine lieutenant, Gillespie had been President James K. Polk’s secret messenger to Frémont, had aided in the Bear Flag Revolt and in The Pathfinder’s capture of California, and had showed great courage fighting Mexican lancers at the battle of San Pascual, where he was repeatedly wounded.

Gillespie had resigned from the Marines in 1854 due to ill health but in March 1862 entered the army and secured a berth as “additional aide-de-camp” to Union army staff chief Gen. H.W. Halleck, who assigned him to Carleton in Santa Fe. So, when Gillespie arrived at Fort Garland, “on special service,” he could, and did, boast some of the highest connections in the land in addition to dispensing the aura of a genuine hero.

Even as a youth, according to a modern historian, Gillespie was “sickly, irascible and . . . arrogant;” and his temper hadn’t improved with age. At fifty-three, he was a ruin of his former self. His face and chest were deeply scarred; he’d lost a front tooth on the battlefield; he was tormented by the chronic dysentery he’d contracted while on his California mission and also by the pain of the lance-wounds taken at San Pasqual, which he was said to assuage with liberal doses of whiskey. If he was, as Eaton later insinuated, an alcoholic, he seems to have found in Eaton’s enemy Lt. Lewis an enthusiastic fellow toper, and perhaps a willing co-conspirator.

– Continued next month

Charles F. Price is a freelance writer in North Carolina with many in-laws in Salida. His most recent book is Nor the Battle to the Strong, a novel of the American Revolution in the South.