By John Mattingly

Not long ago, I was dining out with a friendly group of Republicans who went on and on about the glories of the Reagan years. It’s difficult to stay quiet on this topic if you actually lived in the Reagan years and paid attention. But, before I could give the discussion a booster shot of reality, before getting to the Reagan-guided deregulation of financial systems that laid the foundation for a greed-and-bubble economy, or the Iran Contra Affair in which Reagan “knew in his heart” that he did the right thing even though it was a felony, or before I could get to the bulging taxes and deficits and expansive militarism of Reagan’s actual term in office, a song came over the radio in the cafe …

“Almost cut my hair, it happened just the other day …” the plaintiff voice of David Crosby, agonizing over the possibility that he might cut his hair rather than let his “freak flag fly.” It occurred to me, as I listened to the extolling of Reagan to the background of Crosby, Stills and Nash that my own ponytail hung as a nostalgic reminder of certain mythologies of the 1960s, similar in its selective amnesia to the bloated mythologies some Republicans attribute to the Reagan years.

[InContentAdTwo]

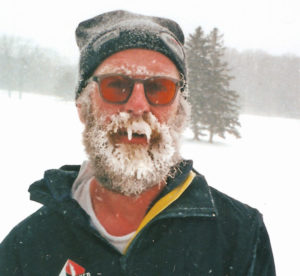

I went home that night, a night of a new moon, and cut my hair with hand clippers, the locks falling into my garden where they were to contribute to the best crop of tomatoes I’ve ever grown. As my freak flag slowly came down to ground, it seemed surprising that something so thin and flimsy could be such a strong symbol. In the mid to late ’60s a man could identify himself as member of a non-specific counter-culture by the simple act of growing his hair. I remember being called a draft dodger, a woman, a drug addict, a ewe in need of shearing, a homosexual, a dirty deviant, and a variety of unprintable names – all just for sporting a ponytail.

In the spring of 1968, while in Kansas on a treasure hunt for parts for my Oliver tractor, I was pulled over by a state trooper and searched after I had stopped for lunch at a cafe in Bird City. The officer expressed real concern about my motives for being in Bird City, referring to the assassination of Martin Luther King, as if the effects could strike at the heart of Bird City and I might be a harbinger of racial tension, a concern that almost made me laugh at the prospect of his presumption of my importance.

Worst of all, though, the officer doubted the existence of Oliver tractors. He had only a John Deere riding lawn mower and, therefore, offered to escort me to a barber. The logic guiding this interaction was right out of the Outer Limits, especially considering that my hair at that point barely covered my ears. Giving in to the force field around Bird City, I followed the officer and got a haircut on Main Street, which drew a crowd, and saved me from getting a ticket for stopping in Bird City for lunch. In much of rural America in the ’60s, longhairs were not welcome in restaurants, were refused some services, and were asked questions like, “Are you one of them hoopers that smokes LDO?”

In the farming community where I came of age, going into a country bar at night with long hair was a challenge to fight. In retrospect, it’s hard to imagine that long hair could incite such controversy and conflict. I’m not sure I could articulate then, or now, what I meant to communicate to the world with a ponytail. Some part of it was perhaps a strange curiosity to experience, to share, to know the prejudices directed at those who were truly discriminated against, and in so doing show some solidarity with them. For some, the freak flag was a genuine expression of advocacy for social change.

The long hair look was also a personal style choice, admired and accepted at times in the past, and in the ’60s was associated with rock stars who attracted followings of young females. Steven Pinker observed that many men coming of age in the ’60s aspired to rock star fame because of its magnetic effect on the opposite sex. Later, some longhairs earned the impression of being a part of the “back to the land” demographic, fond of wood stoves, ice boxes, gardens and Have-More Plans, all of which seemed ironic and curious to Depression Era folks who thought electricity and supermarkets were wonderful innovations.

I had a habit of growing my hair for about four years and then shearing it off to a buzzcut. It seemed efficient to either have long hair or no hair. Getting haircuts and styling hair was not something I understood.

With this latest buzzcut I meant to let go of the ’60s and settle in to the new millennium, late, but better. (Of course, being in my late 60s it’s nice to even have hair). There are few pleasures greater than the first shower after cutting off about twenty inches of hair. Reagan-romancing Republicans could experience the same enjoyment if they gave their nostalgic mythologies of Ronnie a buzzcut. Imagine: a bald Reagan. Even better: a bald Drumpf (his real name). Perhaps Drumpf knows that if he cut off the bull butter there might not be anything left. ?

John Mattingly cultivates prose, among other things, and was most recently seen near Poncha Springs.