By Don Love

The first miners and ranchers in Colorado’s mountain country depended on the rough roads that connected them to each other and to the world beyond. Popular interpretations of western history hold that railroads, which came to the mountain country in the 1880s, gave the region an economic boost that wagon roads had failed to completely exploit.

But the mountain West never could be confined to the routes and schedules that made the rails such a progressive force in much of Gilded Age America. The mountain west traveled a more independent road, and even before the advent of the automobile, a Chaffee County rancher and politician paved the way to a modern highway system. This month, we recognize the accomplishments of Thomas Jefferson Ehrhart, who, 100 years ago, helped establish the agency we know today as the Colorado Department of Transportation.

T. J. Ehrhart was born in Council Bluffs, Iowa in 1859. His parents were from Illinois and were heading for the gold in Colorado when he was born. By 1861 the family had settled in Denver and a couple of years later had made their way to Chaffee County (then the southern part of Lake County), where they homesteaded just south of Browns Creek. As a child, young Thomas watched the daily stagecoaches travel up and down the county highway that connected his family ranch and others in the valley north to Leadville and south to Cañon City. Besides the coaches, there were countless wagons and carts hauling the produce of the valley to the markets and the mines that had made this part of Colorado an economic engine. His neighborhood was a lively community called Centerville, and it owed its vitality to its location on the highway.

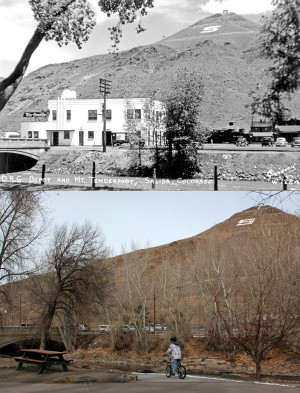

In 1880, the mining and transportation industries, and especially the newborn tourism industry, were poised to transform the Rocky Mountain West; unfortunately, certain locales, like Centerville, were not part of the plan. In order to connect the rich silver mines in the Leadville region and the gold mines along Chalk Creek to processing facilities and transportation hubs in Pueblo, the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad laid track along the Arkansas River from Cañon City through the Royal Gorge to the new towns of Salida and Buena Vista and on to Leadville. However, rather than follow the established roadways that had existed since the first American settlers arrived in the valley in the 1860s, the railroad, in a deliberate move to market tourism, chose a more scenic route along the river through Browns Canyon.

Much has been written about the contribution of railroads to the development of the West, and the histories of Salida and Buena Vista are testament to the positive impact that railroads had on the development of communities. Not as often mentioned in the literature of the West, however, are the detrimental effects that railroads had on communities bypassed by rail routes. Centerville is a case in point.

While the rails provided a rapid connection between parts of the Upper Arkansas Valley and the Front Range, very little changed for the farmers and ranchers along the highway in Centerville. To reach the trains, farmers and ranchers continued to rely on horse-drawn wagons and carts to deliver their produce to Nathrop or Hecla Junction. While railroad development in the 1880s had a generally positive impact on the economy of the West, it did very little for many areas like Centerville.

This fact was not lost on young men like Thomas Jefferson Ehrhart, who was in his 20s when the railroad came to the valley. He had seen first-hand the effects of a transportation monopoly that had skipped his neighborhood in its race to connect Colorado to the rest of the nation. Convinced that a good road was as important as a good railroad, Ehrhart waited patiently for the technology that would revitalize the road in American transportation history.

T.J. Ehrhart had been drawn to public service naturally. His pioneer father had been a territorial legislator beginning in 1864 and an early member of the Lake County Board of County Commissioners following statehood. Following in his father’s footsteps, T.J. Ehrhart was elected to the Chaffee County Commission in 1886, when he was just 27 years old. In 1896, he was elected to the first of many terms in the Colorado General Assembly. During his first two years in the House of Representatives, he worked hard to get adequate funding for roads in Chaffee County. He secured resources to improve the existing county roads that we know today as U.S. Highway 50 and U.S. Highway 285.

In 1898 Ehrhart was elected to the Senate. By this time the automobile was being recognized as the next revolution in transportation. For Ehrhart, the automobile represented a way to return roads to the prominent place they had occupied before the coming of the railroads, and therefore preserved an opportunity to revitalize communities like Centerville that had been hindered by railroad routing decisions.

In 1909, Ehrhart introduced Senate Bill 52, which, after reconciliation with a companion bill in the House, created a three-member State Highway Commission. This marked the beginning of the state bureaucracy that we know today as the Colorado Department of Transportation. The State Highway Commission created in 1909 was hampered in its efforts by the overwhelming costs of road construction in a mountainous state, and its inability to raise revenue. In 1913 new legislation revamped the Colorado Highway Commission and on March 24, 1913, T.J. Ehrhart was appointed as the first professional state highway commissioner for Colorado.

Ehrhart was supported by a five-member advisory board and oversaw substantial funding sources, including a $700,000 appropriation from the state’s Internal Improvement Fund and the introduction of a motor vehicle license fee. Throughout his eight-year tenure in the office, Ehrhart increased the resources available to the State Highway Department largely by linking highway construction to economic development, and specifically as a way to develop the tourist industry in Colorado.

As Highway Commissioner, Ehrhart oversaw some very significant projects, including the grading of over 5,000 miles of roads and the surfacing of nearly 400 more during his first two years. Significant improvements were made to Berthoud Pass, Tennessee Pass, Poncha Pass and La Veta Pass. Each of these routes was seen as a major link between economically important regions of the state. Under Ehrhart, the Highway Commission also developed roads specifically designed as tourist routes. The most well-known of these is the Fall River Road from Estes Park to Granby. (The western portion of this road is today’s Trail Ridge Road through Rocky Mountain National Park.)

The cost of building mountain highways proved to be substantial, and Ehrhart was skillful in his ability to develop funding resources. Simply put, the amount of money required to build a state highway system up to Ehrhart’s standards necessitated a shift in political perceptions regarding government’s role in the economic development of the state. Ehrhart learned his ways during the heyday of the progressive movement in America; he believed that it was government’s duty to finance the sorts of improvements that could not be funded through private sources. His formidable task was to convince the various self-interested political institutions around the state that they shared a stake in the development of a modern transportation network through the mountains. “Colorado’s interests are mutual,” wrote Ehrhart soon after taking charge of the Highway Commission. “Any development in the State, no matter where, will help the whole.” One of the Progressive Era’s most consequential goals was to redistribute wealth. The underserved mountain communities were, for a Colorado progressive like Ehrhart, a deserving beneficiary of some of that redistribution.

Federal transportation policy during this time was ambiguous, to say the least. On the one hand, there were those who, like Ehrhart, saw the automobile as an eventual replacement for rail travel. On the other hand, there were those who believed that the railway station was the terminus for roads. They refused to accept the possibility of either freight or passengers traveling over long distance highways. Nevertheless, Congress passed the landmark Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, which appropriated $75 million over five years. The act remains one of the most far-reaching passed during the Wilson administration, for the reason that, like so many others, it represented the growing involvement of the U. S. government in local affairs. The immediate impact on Colorado was the need for a restructuring of the highway bureaucracy. Since 1913, Ehrhart had led an agency with limited power, lacking the status of an executive department within the state government structure. The 1916 federal highway law required states to administer their highway programs through an executive department. Colorado was one of 15 states not in compliance with this requirement. To receive federal assistance, the legislature responded in 1917 with a new highway law.

As a result of the new law, Ehrhart became head of the State Highway Department, an executive agency that had much higher public visibility than the previous Commission. Ehrhart recognized the value of increased public awareness of his department’s activities. In 1918, the department began publication of Colorado Highways Bulletin, a slick monthly magazine with the dual purpose of encouraging cooperation between state and county officials in road building and of promoting tourism in the state. The Bulletin featured a variety of articles, from highly technical tips on bridge and culvert design to field notes from each of the state’s five highway districts. Each issue also contained a lengthy narration guiding potential tourists along one of the state’s scenic mountain routes. Ehrhart’s magazine made driving a recreational activity.

By 1921, Ehrhart headed an agency with a budget of $6 million, an impressive increase over the $800,000 the Commission spent in 1913 when he took control. The Highway Department was a self-sustaining agency, earning all of its considerable revenue from dedicated taxes and fees, as well as from the sale of bonds; Ehrhart enjoyed a measure of independence from the legislature unlike any other executive branch bureaucrat. One indication of the Highway Department’s spectacular rise in fiscal prominence is the increase in its receipts from 1916 to 1920. In the biennium that ended Nov. 30, 1916, the State Road Fund, from which the department drew all its warrants, took in $914,716, or 9.36% of the total state revenue of $9,767,853. Four years later, the Road Fund and the newly created Highway Fund had combined receipts of $5,580,713, or 17.86% of the state’s revenue of $31,248,058. This kind of wealth did not go unnoticed among Colorado’s conservative politicians, who were determined to rein in the well-financed bureaucracies created during the height of Colorado’s progressive movement. The Highway Department was about to be reorganized, and Ehrhart would be a most significant casualty.

Indeed, the Legislature passed a new highway law in 1921, the third one in eight years. In its reorganization of the Highway Department, the Legislature did away with the Highway Commissioner’s job, giving executive directorship of the Department to the Governor and a State Highway Engineer, assisted by a seven-member advisory board. In May 1921, Governor Oliver Shoup was forced by the Legislature to fire Ehrhart.

Ehrhart’s eight years as State Highway Commissioner provide a complete picture of his application of Progressive Era public administration, and presents him as a model of Rocky Mountain progressivism. Under his leadership, the Highway Department exemplified the ideals of the Progressive Era. It was activist, it was professional, it was optimistic. In state administration of highway construction, Ehrhart accomplished the very thing that reformers of the urban political machine were hoping for: the reassignment of public spending privileges from elected to appointed officials. His ceaseless pursuit of economic opportunity for the state through public works places him at the very center of progressive business thought. Above all, Ehrhart had faith that government offered Colorado the best solution to its problem of economic development. In all these ways, he was a model progressive.

In May 1921, Ehrhart quietly left the office he had occupied for eight years. The only parting advice he gave the governor with respect to the continued operation of the Highway Department was that his successor “take immediate action to protect” department employees who he feared might have their positions placed in legal jeopardy during the reorganization interim. Following his departure from the agency he had built, Ehrhart settled down and spent nearly ten years as a sales representative for a tractor dealership in Denver. He returned to his Centerville ranch in 1929 and was elected to another two terms in the state Senate in the 1930s, where he spent most of his energies working on massive water redistribution programs. He died in 1949.

Today, his name is inscribed on the Stone Bridge just off Highway 291 north of Salida. This memorial is but a small reminder that Chaffee County produced one of the most important Progressive Era politicians in Colorado history and a man who can rightfully be considered the “father of modern highways” in Colorado.

Don Love is a teacher in Severance, Colorado. He knows where T.J. Ehrhart’s Model T is hidden on the family ranch in Centerville, but he’s not telling anyone.