Article by Tim Kregel

Recreation – January 2006 – Colorado Central Magazine

IT WOULD HAVE BEEN about March of 1974, when the buds and I decided it was high time to have a new ‘hinterland adventure.’ Not that we hadn’t had sufficient adventures that winter, living in and around Garfield. We had adventures that winter, all right — we’d even said permanent goodbyes to a couple of the buds who’d gotten more adventure than they had bargained for.

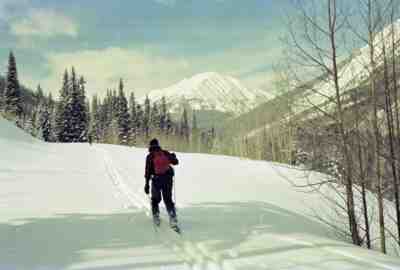

To be fair, we’d had some good times among the peaks as well, enough that I had more or less mastered the fine art of backcountry skiing on the wooden cross country skis and bamboo poles that were available in those days. On this less than substantial lumber, we had skied most of the obvious places around Monarch including Marshall Pass and Fooses Creek from the Monarch Crest, and had done a lot of trips off the top of Monarch to Water Dog, Boss, and other frozen lakes. But with the first hint of the coming end of winter in the air, we were in need of one last hinterland adventure to top off the snowy season.

As I recall, the things that separated a true hinterland adventure from its more average siblings were (1) the novelty of the undertaking, (2) the degree of planning and organization required, and (3) the overall likelihood of failure due to too much of number one or not enough of number two.

And so we began casting about for something worthy of the moniker. All of us had spent a night or two in the old miner’s cabins near the slide on Mt. Aetna, and had occasionally ventured beyond, towards the headwaters of the Middle Fork of the South Arkansas. On one of these outings it finally hit us — just keep going up and over Chalk Creek Pass and ski all the way into St. Elmo. Now that’s hinterland!

ON REFLECTION, we realized that doing the trip in the other direction would be smart(er). That way, we’d start out on a relatively gentle grade heading out of St. Elmo instead of huffing up the more daunting Middle Fork, and we’d spend the last part of what would be a long day skiing through more and more familiar territory instead of less and less well known terrain.

And either way, we were unaware of anyone else previously making that trip on skis which certainly satisfied criterion one of a hinterland adventure, and we had a fair degree of research and equipment selection to do before setting out, meeting criterion number two.

DUE TO incompatible schedules at work and a general lack of interest among some local denizens, we finally winnowed the participants on this adventure down to just five: Steve, Greg, Ned, Ned’s aptly named German Shepard, Schnee, and me. Some of our pals didn’t think this particular adventure was such a great idea. Backcountry skiing had already taken three lives that winter in the Monarch area, and the route we were going to attempt had some limited but unavoidable avalanche danger near the crest of Chalk Creek Pass.

We were all well aware that four people breaking trail uphill in more or less untouched upland snow is about one less than you’d really want on a long trip, because the leader and number two might as well be wearing snow shoes, the third has only a slightly improved trail and the fourth in line is the first to be actually skiing. As you rotate through the positions, a fifth person means twenty percent less time at the front for each participant, saving significant work.

But shorthanded or not, preparations soon began in earnest as we consulted the Garfield and St. Elmo USGS quads. The route looked fairly straightforward, heading southeast from St. Elmo along Chalk Creek to the Hancock Lakes, over the summit of Chalk Creek Pass at just over 12,000 feet, and downhill along the upper Middle Fork of the South Arkansas River passing Mt. Aetna and Taylor Mountain enroute to Garfield. As the crow flies, Garfield is about eleven miles from St. Elmo, so we estimated the actual distance to cover on skis at around twelve or thirteen. Breaking trail in virgin snow, combined with climbing over 2,000 feet to the pass, yields a skiing speed of one or two miles an hour, so we allowed about six hours to get to the pass and maybe two more to get down the south side where the force of gravity and the resultant speed would be our friends.

BECAUSE NONE OF US had actually been over Chalk Creek Pass — even in the summer — we’d take the quad maps and a compass. The trip was planned about 25 years too early to take a GPS receiver, with which you can now plot your location anywhere on the globe in about 30 seconds. Owing to the fact that none of us had a lot of “discretionary cash” in those days, we didn’t even have an altimeter/barometer, which can be real useful when you’re trying to locate your position (or at lease elevation) in a blizzard — although it’s not in a league with GPS.

Much of our other gear was a collection of cost-induced compromises as well. Individual avalanche beacons, being way above our personal spending limits, were supplanted by “avalanche cords” — long red nylon cords tied around the waist, some part of which would float to the surface aiding search and rescue even if the wearer got buried under a snow slide (at least in theory). Sustenance would consist of sandwiches, gorp and maybe a little Kool Aid.

The one item that was not skimped on was clothing. Each of us wore or packed a selection of wool and down clothes and coats, sufficient to keep us from freezing if forced to spend a night in a snow cave or other emergency shelter. Finally, skis were cleaned and had pine tar heated into their bases to better accept the chewing gum that passed for cross-country ski wax in those days.

Early on the designated morning, Ned’s wife Chris, who’d volunteered to act as “transportation slave,” drove us all from Garfield to St. Elmo in their big 4X4. By 8:00 that morning, we were breaking trail in the bright sunshine and heading uphill past the old mines and mills along the way. Chris had offered to let me use her touring skis — metal edges and all — that were better suited to the alpine conditions.

It was a nice gesture, and with a keen lack of foresight I accepted, knowing full well that the only boots I had that fit her skis were nearly brand new and likely to be blister-makers. Somewhere before timberline I had a nice set of quarter-size blisters going, despite my best efforts at keeping some first-aid tape on my heels.

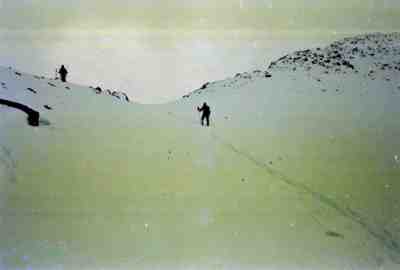

After about four hours of slogging, interspersed with obligatory food, relief, and equipment breaks, the trail ascended above timberline and the world started to drop away around us as happens when you near a pass or summit. The bright blue sky was interrupted only by the snow and rocks above, and a bit of a “ridge runner” hanging over the pass and higher terrain to the north and south.

As we left the relative safety of the forest, we did our best to mitigate any snow slide danger by deploying our avalanche cords, keeping a good deal of distance between each of us (say, one avalanche chute’s worth) and staying high on the east side of the pass where the snow was shallowest and where the rocks above us were nearly scoured clean by the wind.

An hour’s worth of switchbacks and sweat and we stood atop Chalk Creek Pass, stopping just long enough to scrape and rewax the boards for the downhill run, and to allow our sweat and steamy breath to mix with the light snow coming down to form a nice rime ice on our mustaches and eyebrows. Occasional glimpses through the cloud revealed the long trail back north to St. Elmo, and in the other direction, Mt. Aetna, the relatively straight shot down to Garfield, and a distant view down south toward the Sangre de Cristos.

WE SKIED the decent powder snow off the south side of the pass one at a time, stopping when we arrived at the pines below. Not only do trees provide a good bit of avalanche protection, they also provide outstanding — if unwanted — stopping power when your avalanche cord wraps around one because you’ve forgotten to stop and reel it in during all the excitement.

The 20 minutes of pure fun getting down off the pass went by too fast, and we found ourselves breaking trail again along the deeply buried jeep road that we had all hoped would be steep enough to really ski. The grind down to the cabins at Mt. Aetna took a fair bit longer than expected, but we knew that last couple of miles down to Garfield from there were always a flier.

And so they were. Aside from the few minutes of fun off the top of the pass, it was the only other fast skiing of the day. Late in the afternoon we pulled into Garfield, me hobbling across Highway 50 with silver dollar size blisters on each heel. A couple libations later and some dinner and I felt better even if my feet didn’t.

For the rest of that winter (or at least as long as people would listen) I had torn up feet as well as bragging rights as one of the first people (and canines) to cross Chalk Creek Pass via skis, or so we believed. The pass may have been crossed by a thirsty miner or two in the winter, but that would likely have been on snow shoes. In the 1970s, skinny skis were the domain of a few die-hard Scandinavians who raced prepared tracks on them, and a few crazies living among the high peaks. But I do expect to hear a number of different opinions regarding the novelty of our undertaking.

Tim Kregel lives at the edge of Germany’s largest forest these days. The skiing there is hardly ever any good, but the mountain biking is supreme.