Review by Ed Quillen

Colorado History – November 2004 – Colorado Central Magazine

Brothels, Bordellos & Bad Girls: Prostitution in Colorado 1860-1930

by Jan MacKell

Published in 2004

by the University of New Mexico Press

ISBN 0-8263-3342-7

IF YOU LIVE IN Leadville or Salida, you probably know the location of a notorious whorehouse, and you point it out to visitors: “There’s the Pioneer Club, and Ma Brown ran the place into the 1970s,” or “That’s Laura Evans’s old parlor house, across the street from her cribs, and local legend has it that she willed it to the Shriners in appreciation for all the business they’d given her over the years. ”

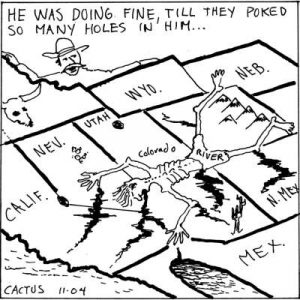

Although the tenderloin districts of Leadville and Salida get their due in this book, they’re only part of the story of prostitution in Colorado, which began before there were even prospectors (a young Mexican woman named Nicolasa apparently practiced the world’s oldest profession at Greenhorn in 1841, and draymen along the Santa Fé Trail could rent companionship near places like Bent’s Fort). And the profession continues to this day (as an excursion along East Colfax Avenue in Denver will demonstrate).

While plenty of books and pamphlets have been written about Colorado’s “soiled doves” and “fallen angels,” most have focused on a few madams, or else on one town’s red-light district. (The term comes from railroaders, who left their signal lanterns on the porches so that they could be located quickly if a call went out for a train crew).

Brothels, Bordellos & Bad Girls is different in that it attempts a comprehensive history, covering the entire state, as well as the careers, not just of the infamous madams who ran elegant parlor houses but of the “brides of the multitude” who worked in those houses — and in one-room cribs. Some retired with a degree of wealth and respect, some married and lived reputable lives afterward, some committed suicide, many died of disease. Name the cliché, from the hooker with the heart of gold to the tormented soul who overdosed on morphine while still a teenager, and there are historical examples, listed in this book.

What most of them had in common, though, was a false identity, and they changed their names frequently, almost as often as they moved to another town. Thus, as the author explains, it’s nearly impossible to provide much biographical detail.

Even so, there is a surprising amount of such information here, thanks to census records and city directories of the era. Census-takers just wanted to gather data, not pass moral judgments, but they gathered information on citizens’ living arrangements and occupations, and that information sheds some light on women who might otherwise have remained anonymous. In city directories of the era, brothels were usually included as “female boarding houses,” a euphemism that can be coupled with census records and police reports to extrapolate information about individual prostitutes in a town. For instance, we learn that in 1910, Trinidad had nine madams, who ranged in age from Margarita Carillo, 24, with three employees, to Sarah Cunningham, 58, who had nine children.

MOTHERHOOD WAS NOT uncommon among prostitutes, and that was something of a surprise to me when I read this book. Prostitutes did practice birth control, but the methods of the day were often ineffective, and they often bore children. Some offspring were given to relatives to adopt, but many grew up in the whorehouse, where they lived rather lonely lives because other kids wouldn’t play with them.

This book also examines the relationship between prostitution and Victorian society. Any time you have a surplus of young men (be it at a frontier mining camp or near a military base today), human nature almost insures there will be prostitution. The Victorians did not attempt to eliminate it, but they did try to regulate it with zoning. They also tried to keep the ladies of the evening in their own part of town, sometimes setting aside one day a week when they would be allowed to shop in the respectable part of town.

Many Colorado towns established a scale of fines, which turned into what were essentially licensing fees — that is, a fine of $100 per month for “maintaining a house of ill-repute” quickly became a $100 per month fee, and the municipal treasury came to rely on such levies.

Colorado prostitution began to decline early in the 20th century, for a variety of reasons. The bloom was off the mining boom, and once-wild spots like Leadville and Cripple Creek had stabilized with family men, rather than get-rich-quick single prospectors. The reformers, led by the allied suffrage and temperance movements, were gaining power; Colorado went dry in 1916, several years before national Prohibition. With the saloons and dance halls closed, the prostitutes had fewer places to meet customers.

BY 1930, the day of the parlor house had passed, except in a few backwaters like Leadville and Salida. Both get considerable attention in this book, along with Cripple Creek and Colorado City (which flourished for a while by providing thrills that weren’t available in its then-dry neighbor, Colorado Springs). Prostitution may or may not have been more prevalent in these towns; the only sure thing is that there are more written records surviving regarding brothels and prostitutes in these towns, and that’s what a historian must rely on.

Just about every Colorado cat-house story I’ve ever heard is in MacKell’s book, along with all of the well-known practitioners, like Silver Heels of South Park and Cock-Eyed Liz of Buena Vista. This book’s reach also contains many more tidbits, including, for instance, the poetic obituary of a Ouray prostitute:

Here lies Charlotte

She was a harlot

For 15 years she preserved her virginity

A damn good record for this vicinity.

There’s also information about brothels out on the plains, a truly rare inclusion. And there is also this sad local reflection:

“Elizabeth Enderlin, a.k.a. Cockeyed Liz of Buena Vista, once made a poignant confession to her housekeeper. “‘I’ll have to pay for the awful things I’ve done, won’t I?’ she said. ‘I couldn’t help myself when I was young, but oh all the little lives I’ve destroyed — that’s what I’ll have to pay for — all those little young lives.’ Liz died at age seventy-two in 1929 of a heart attack. Even then, with all of her remorse and after thirty years of respectable marriage, it is said the churches in town refused to hold services for her.”

But that quote had one thing I found annoying in this book: the frequent use of “it is said.” The author doesn’t say who said it, or when or where it was said. Instead, she uses this cliché as a sort of shorthand for “gossip has it that, but there is no way to be sure.” Although, I realize that a book on this topic has to reach into that realm, there are surely other phrases that could make it clear that the information is hearsay — or perhaps MacKell should have discussed the likelihood of some of those rumors.

BUT I SAW only one glaring inaccuracy: “Farther north on the western slope was Leadville.” The last time I checked, Leadville was on the Eastern slope, and that shouldn’t be too difficult to determine since it’s on the Arkansas River (which, as its name clearly indicates, flows east toward Arkansas). The book also refers to “Laura Evens” while I prefer the more common “Laura Evans,” but that’s something history buffs like to argue about, and not actually an error.

Whether you’re a buff or not, this is a good history. The writing is engaging, the book is decently organized, and it offers thorough source notes, a useful index, even a glossary. The subject is fascinating, and Jan MacKell explores and explains it without lapsing into sensationalism or sentimentality.

— Ed Quillen