The Cowboy Takes a Wife

By Davalynn Spencer

ISBN-13: 9780373486977

Publisher: Love Inspired, 2014

Reviewed by Elliot Jackson

Ah, the “historical” romance novel! Casually dismissed by the non-cognoscenti as “bodice-rippers,” the classic formula is this: take one beautiful and spirited (also penniless, orphaned or in some way materially disadvantaged) heroine, and one handsome, studly, often lordly and always rich hero; add instant mutual attraction/antagonism between same; set in an “exotic” historical setting of some sort or other; mix well with other ingredients including villainous Other men and scheming Other women, and sex – lots of unashamed, lusty and usually premarital sex. Ah, the good old days.

That is, unless you’re talking about the “Christian romance.” What makes a romance novel “Christian”? Well, if The Cowboy Takes a Wife is any example, a lot of furrowed brows and Bible quoting. But first, let’s meet our hero, Caleb, whose story can be summed up thus: Preacher Boy meets girl. Preacher Boy loses girl, and therefore also faith in God and calling. So then, Preacher Boy does what any red-blooded, mid-19th-century American loser would do: he heads west, to take up an occupation for which he is ridiculously underqualified – he’s gonna be a cowboy!

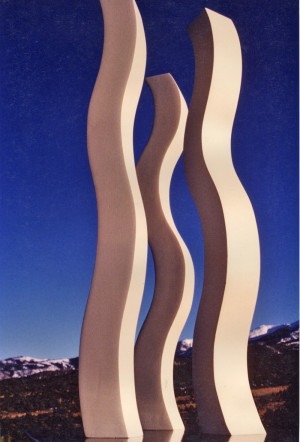

Next, we meet our heroine, Annie: a “plain Jane,” as she gets described on the book jacket. In this case, Annie is not exactly “plain” so much as “spunky spinster who envies her sister her plump blond beauty and chooses to light out West so she won’t ever have to be compared to her again.” Oh, and where she will get her pick of loser cowboys and villainous barkeeps in Cañon City, Colorado. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

On the other hand, Annie, despite being “plain,” does has something in common with the classic romance heroine: she’s “spirited.” This, as in most cases, means she’s bitchy to the hero with no particular reason save that he rubs her the wrong way, and she has a fatal jones for getting herself into sticky situations that she can’t get herself out of without the hero’s intervention. Only in this case the hero is God, and Caleb, our “hero,” is only His tool – make sense? For example, Annie attracts the amorous attention of her villainous landlord, who attempts to rape her. Just in the nick of time, as she’s praying for deliverance, along comes Caleb who, wielding the fists of righteous fury on God’s behalf, punches out the villain.

Now, this is not to make light of rape, or prayer. Millions of women for thousands of years have found themselves praying for deliverance from rape at the hands of enemy soldiers, evil boyfriends, male relatives or landlords with a sense of entitlement. In the case of most of these women, however, God has tended to help only those who could help themselves; more often than not, there is no studly hero on hand to deal out instant karma. If Annie had been a bit more like the heroine of musician Gillian Welch’s Caleb Meyer, she might have prayed to God for deliverance and then found a bottle neck to slit the bastard’s throat with, which would have not only brought deliverance but also a whole lot of interesting complications for a good Christian romance heroine. Lots of heart-burning, soul-searching complications, like: “Wow, so I killed a guy who was trying to rape me; why do I still feel like a slut?” Or even just, “Honey, I know God will still love me when I’m stuck in the Cañon City Jail, but will you?”

However, this author has no intention whatsoever of exploring any such issues. She’s interested in getting good old Caleb to come back to the fold and become a nice preacher man again, so that Annie can fulfill her destiny, as outlined in the last line of the novel: “the journey of her life as Mrs. Caleb Hutton.”

And I guess here is the moral qualm I feel as a feminist reader when confronted with a “Christian romance novel,” which is only an intensification of the quandary I feel when confronted with the romance genre: at its heart, the romance novel is about courtship and marriage. In the right hands – Jane Austen’s, for example – courtship and marriage rituals become an opportunity to explore, challenge, and satirize society, gender relations, and conflicts of duty to family and self. In most hands, however, the rituals of courtship and marriage become a way to solidify women’s “proper roles” as Mrs. Some Man’s Name and – God willing and I don’t die in childbirth – Some Man’s Mother. If that’s going to be the case, I’m going to need a bit more than some chaste kisses and modest flutterings in the maidenly bosom. Give me some good old-timey bodice-ripping, with the invocation of God’s name limited to bedchamber ecstasies.