By Patty LaTaille

When I was asked to write a story about Bill Forrest, I hesitated briefly. Having met Bill during an interview assigned by The Mountain Gazette, I spent a number of fascinating hours listening to his stories and poking around his workshop filled with all sorts of innovative climbing devices and snowshoe models. He introduced me to his wife Rosa, and so began a friendship of shared meals, chance meetings and a memorable snowshoe adventure at Beaver Creek, in which Bill in his ever gracious manner shoveled out my Subaru not once, but twice from neighboring snow banks.

I hesitated only because after Bill passed, on Dec. 21, 2012, from a heart attack while snowshoeing on the Waterdog Lake Trail by Old Monarch Pass with Rosa, he became a legend – and not only in my mind. His memorial service, held at First Presbyterian Church in Salida, was quite touching and gave a voice to many of Bill’s friends in celebrating his life and mourning his untimely death. Writing an article on Bill’s life is an honor and a sincere responsibility to represent Bill in a way that his friends and family would appreciate. The love and admiration for Bill and his endeavors runs as deep as his love for Rosa and his outdoor life of work and play.

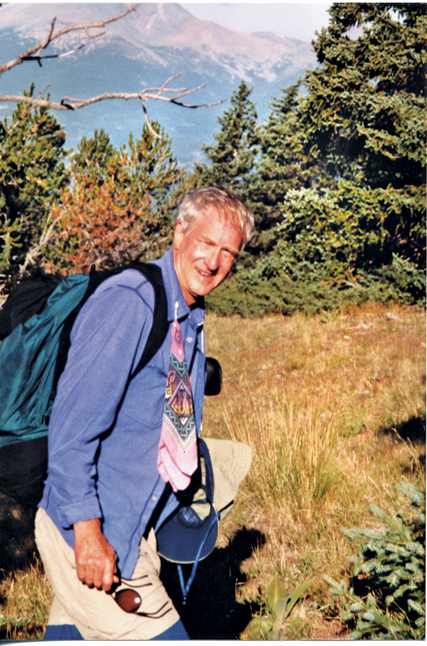

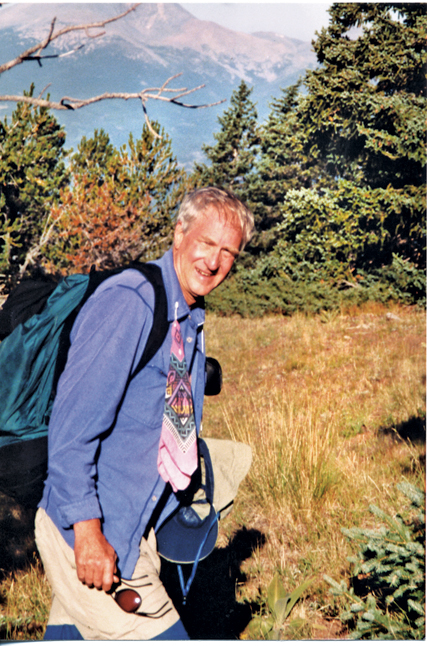

Long, lean and lanky at age 73, Forrest had been married to petite Rosa, his hiking and snowshoeing partner, for 26 years. With his vitality and activity level – he had hiked all 54 fourteeners and the 500-mile Colorado Trail – while living in and telecommuting from his “Happy Trails Hacienda” in Salida, Bill wasn’t anywhere near grizzled old age. He knew he was living the good life – complete with a true vegan diet – and was happy to share health info with friends and acquaintances. Bill always had his eye out for possible new climbing routes – “Why mess around with the old ones?” he’d say – and saw retirement as an adventure he shared with his friends and the artistic Rosa. He planned to author a book and more climbing articles, and to keep repeating the “Salida Slam,” climbing the 22 peaks visible from his home.

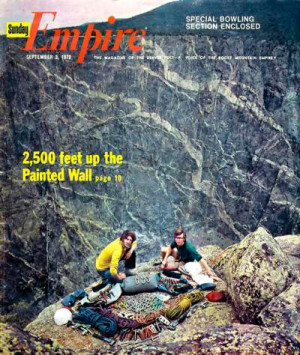

Bill, originally from Glendale, California, maintained a low profile for someone who had been developing new inventions in the world of gear for nearly 40 years. His climbing equipment designs won international design awards, with his Mjollnir Hammer, the original hammer with interchangeable picks, is on display in the Smithsonian Institute. Bill learned to climb at age 19 while stationed in Germany with the U.S. Army. He became a legendary climber with numerous first ascents on several continents; Uli Biaho in the Himalayas, regarded as “the hardest sustained rock climb in the world;” the East Face of Baboquivari Peak in Arizona, where he hacked his approach with a machete and confronted a mountain lion on a tiny ledge; and in Colorado, the intimidating Painted Wall and Wild Bill’s Wall in the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, as well as the first solo ascent of the Diamond, the east face of Long’s Peak. All of these give you a glimpse of this man’s imposing climbing credentials.

Bill was an inventor of world-renowned climbing gear and a former designer and field tester for Mountain Safety Research (MSR). When asked for his take on good gear, he would insist it was all about performance. “As a user,” Bill said, “I hate for gear to fall apart on me, especially in the backcountry. I want my gear to function. Who wants to skitter off a traverse in a snowshoe? I can do better.”

Note the emphasis on “I.” Bill’s statement is not ego-serving: he has done better. He created some of the best gear on the market,used it, and was paid well for his designs. He designed MSR’s Lightning Ascent snowshoe with the patented Televator (wire heel lifter designed to ease the strain on calf muscles on ascents), which remains a hot model on the snowshoe circuit.

“Customers love gadgets, whether they work or not,” said Bill. “That’s why getting it right is so important, especially if you’re manufacturing equipment for people to hang their lives on.”

Your life may not be hanging by the traction blade of a snowshoe – yet – but Forrest adapted and improved numerous equipment designs, so that if you were left hanging on any of his gear, you’d be in a good position.

Bill was the founder, owner and director of Forrest Mountaineering, a company that for 20 years specialized in designing high-end equipment for technical mountain climbers. He reveled in his own hands-on learning environment and manufacturing plant. He literally absorbed materials information, and if he could dream it up, it could usually be made with the materials and connections he had envisioned. In 1968, he started his company in the basement of a huge old rambling house in Denver that he ran as a boardinghouse and think tank for climbers – all the better to run field trials with. Climbers needed the gear, and he needed the feedback. “I knew I wasn’t the only one having these gear issues,” he explained.

“I want the gear to work better. If I take a fall, I don’t want to get hurt,” Bill noted as his motivation for designing gear in pursuit of his climbing passion. As a former English teacher with a degree from Arizona State University – writer turned inventor, Bill didn’t exactly fit the archetypal gear designer and engineer mold, but his linear thinking process did. First he identified a problem, such as why early snowshoe designs didn’t have a real grip on the snow situation. Then his creative problem-solving mode kicked into high gear and he started designing a solution: a better product that actually worked the way it should.

“I tinker with it until I get close to what I want. Then I make a prototype and build it to suit my specs,” he explained. This was a man who knew materials and how to test them for safety, so you could trust his expertise

This genius gearhead didn’t want to just change the world – he was determined to make it better. The groundbreaking climbing gear he created was only the beginning. Bill’s six snowshoe designs in the last decade certainly improved the overall snowshoe situation on the trails and in the backcountry. (MSR’s breakthrough Denali design was his brainchild, which American climbing legend Jim Bridwell endorses as “the one that outperforms all others.”) Bill was also pretty hip on the marketing end of the outdoor industry, which he said affects what recreationalists buy and wear. He shared, “The marketing pitch has to be successful, it doesn’t matter how good your gear is – without good marketing to the right audience, it won’t sell.”

Those who get to play in the outdoors – professionals and the rest of us – appreciate Bill hanging his own rear on the line for our safety. Forrest Mountaineering gear that he invented, designed and produced 30 years ago is still in use, and in demand today. Jim Bridwell’s endorsement continues “Without a doubt, Forrest Mountaineering equipment is unexcelled in both functional design and durability. It’s a great relief to not have to worry about my equipment breaking in a life-or-death situation.”

As Gerry Roach, who summited Mount Everest in 1983, succinctly stated, “When I’m going for the summit, I want Forrest gear; it’s already been there.”

When you’re stepping into that comfortable climbing harness while you plan your route up the rock – Bill Forrest is the man to thank. He came up with the swami belt with adjustable leg loops made of nylon webbing after he began climbing in Germany with the standard safety harness of the time – 17 feet of one-inch tubing wrapped around his waist. A few good eye-opening “whippers” later, and the climbing community saw a newly designed harness show up on the rock.

“The answers always come if I know what the problem is,” Bill explained. He lived by the quote, “To believe in your heart that what is true for you is true for all mankind – that is genius.” Roughly attributing the words to Ralph Waldo Emerson, Bill paused. “Mankind may not recognize the gear for what it is initially, but they come around.”

“Necessity is the mother of invention.” Bill followed that quaint adage as he invented the Pin Bin – the first piton and nut gear rack (with a coat hanger and a sling design) – because his gear was tangling up on climbs. He also spent one hellacious night in a hanging belay seat on a big wall climb; he came back to his shop and designed a hammock that worked for actual dozing during overnight bivouacs. After a wall hammer broke mid-climb, he replaced original wooden hammer handles with a fiberglass design that was lighter and that wouldn’t get trashed. Forrest’s Daisy Chain design came to him when he was struggling with haul bags on a big wall climb. He needed an infinitely adjustable nylon webding chain that enabled him to anchor quickly and haul efficiently. He was a man who could see the need and fill it.

Safety and comfort were his big motivators in improving the climbing experience. Never wanting to have an adventurer get hurt in his gear, Bill subjected his inventions to rigorous testing by hardcore climbers, including himself. He was quick to credit his climbing partners, along with the engineers and designers he worked with, for his success as a product designer.

Ray Jardine, world class adventurer, inventor of the Friends (rock wall crack camming devices), and early climbing partner and housemate of Forrest, described him as “a landmark in the history of Colorado climbing … on the walls he was virtually unstoppable. He is among the era’s greatest manufacturing minds, (having) developed many new and original products.”

Jardine worked for a short while in Forrest’s basement. He credited Forrest for teaching him “to think outside the box – to think of possibilities beyond the norm.” He added, “This mindset set the stage for my own inventions, including the Friends, which Bill very kindly allowed me to prototype in his shop.”

Field tests – a source of excitement of the unknown – could be epic, as when Bill tested his first harness design on a multi-day climb in Zion and discovered that the buckle on his leg loops wouldn’t stay cinched. Upon his return home, he designed his own buckle that exceeded the standards of the Union of International Alpinists Association standards and is the only one fully rated for safety with a single pass.

In 1985, Forrest Mountaineering came out with the Triton – a single piece of gear that functions as a combination nut, belay plate and rappel device – which evolved from Bill’s desire to minimize the amount of gear he carried.

Having sold his company to Olsen Industries in 1985, and ready to embark on a new adventure, Forrest started up ForrestSmith with a partner and developed a new snowshoe design that received immediate notice. Two weeks after introducing the snowshoe at a trade show, the president and research and development manager of MSR contacted him with an offer to buy the design rights and hire him full time to focus on snowshoes in their R&D department.

The desire to build a better snowshoe spurred him to leave Denver after 30 years and find a place with better access to the mountains. “I hated being in the heavy traffic on the Front Range – it was hard to get out and back in the same day for field trials. Now I can be up at a trailhead in twenty minutes. You can’t beat Salida – good clean air and easy access,” he explained happily.

With the Gear Muse hovering nearby and his belief in a higher power that had carried him through hundreds of close calls, Bill was always ready to sketch ideas with pen and paper by the bed at night and had a steadfast conviction in their success. He was positive that with enough thought and a strong belief system, he would solve the problem. “I’ve got certain design ideas constantly cooking in my head,” he confided with a smile. “Part of my religion is being in the mountains with wide open spaces and fresh air – that helps a lot.”

From Nate Porter at Salida Mountain Sports:

I was probably 16, 1984 or so, just getting in to climbing, and needed a rope. Growing up in Denver, Forrest Mountaineering was the place to go for climbing gear at the time. It was a Sunday, and I was anxious to go, so I called up Bill. He answered the phone, even though Sunday was normally a day he was closed. I told him what I needed, and he said come on down, he’d let me in and sell me a rope. We chatted a while and he sent me on my way, probably thinking, “good luck out there kid”. He could tell I was excited about getting into the mountains in a different way, and it was nice of him to open up for me on a day off. I still have some Forrest gear on my rack, and still have the rope. Of course it has long since been retired from climbing, but still gets used as a tow rope, to tie lumber onto the rack, and all the things an old rope are good for.

Here are some links to stories about some of his notable climbs.

http://www.supertopo.com/climbing/thread.php?topic_id=2027415&tn=0&mr=0

Beyond his contributions to the climbing world and outdoor industry, Bill was just a good person. A gentle, kind man with a good perspective on the world. He knew what’s important and what isn’t. After I moved to Salida and realized that he lived here, I always enjoyed talking to him about things, and he seemed to enjoy keeping up on the outdoor business and talking gear.

Nate Porter, Salida Mountain Sports – www.salidamountainsports.com