By Forrest Whitman

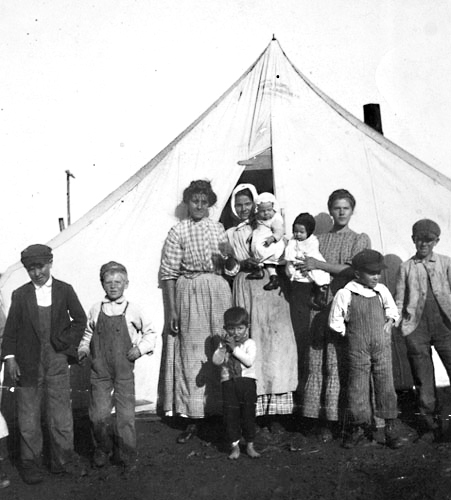

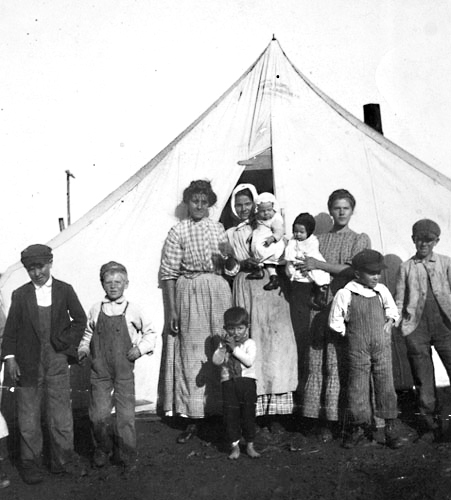

History in Colorado doesn’t quite repeat itself, but (as has been often said) it rhymes. President Obama’s push to raise the minimum wage to $10.10 an hour hauntingly reminds me of the Ludlow Massacre. It happened exactly 100 years ago on April 20, 1914. Somewhere around 39 coal miners and their families were killed and an uncounted more were wounded by Colorado militia and company security guards. Some woman and children died as they huddled in dugouts under the tents as they burned. These were coal miners and their families out on strike against CF&I (Colorado Fuel and Iron). They were living in a tent city at Ludlow after being kicked out of company housing for joining a strike. That strike was about many things, mine safety especially, but another issue was the way the miners were paid in script only useable at the company stores. The most basic strike objective, reminiscent of President Obama’s campaign, was a livable minimum wage.

A few shots were fired toward the troops at what’s been called “the battle of Ludlow,” but it wasn’t much of a battle. The company did “damage control” afterward but had a hard time painting life in the company towns as rosy. The union had often used pressure tactics (especially scorning) to get members. The company press releases about beatings of non-union men were denied by even strike breakers. As usual, the union lost in that strike, but some things changed. Wages didn’t go up, but most mines stopped paying in company script.

The big change was the fact that John D. Rockefeller, Jr. took an interest. He was rich, comparatively almost as rich as our top one-half of one percent today. It caused something of a sensation when Rockefeller began to visit the mining camps. While the company never gave in to the union, (and wages stayed the same) he did come up with the “Rockefeller Plan.” This allowed for worker representatives to speak to management. Conditions in the camps did improve and the camp schools began to get better, as did the health care. One could argue the company did this just to keep strikes from happening, but the “plan” had positive effects.

Life wasn’t all bad in the camps. Everyone shared the grief when men were killed and maimed. Some estimate that 20% of the work force eventually shared that fate. There were big parties on Saturday night. After all, these families were largely Italian and Polish immigrants. They had parties no matter how tough times were. The sense of community was real.

Perhaps some of our readers will visit what’s left of the coal camps this summer. The bituminous coal beds run roughly from Trinidad to Walsenburg for one leg, and then another leg runs from Trinidad up the Purgatory River Valley as far as Tercio. There are foundations of camps all along both legs. The old D&RGW rail line is still in fair shape up to Tercio. With enough imagination, one could still hear a squeeze box playing on the wind. Maybe names would blow back, names of some killed at Ludlow that day, like; Frank Rubio, age 23; Lucy Costa, age 4; Patria Valdez, age 37; Frank Petrucci, aged 6 months; Ferelina Costa, age 27; and on and on.