Article by Sunnie Sacks

Livestock – November 2004 – Colorado Central Magazine

AMY MORRISON decided to adopt and train a wild burro as a learning project for her job. At work, she supervises inmates who are training animals at the Colorado Department of Corrections in Cañon City. But Amy started training horses on her parents’ ranch outside of Guffey when she was only 12 years old.

Three years ago, Amy started working with prison inmates training animals for the Wild Horse and Burro Adoption program. Inmates who volunteer for the program are carefully selected and screened for this educational and employment opportunity. Each inmate participates in approximately 200 hours of classroom and practical instruction before being qualified to train wild horses and burros.

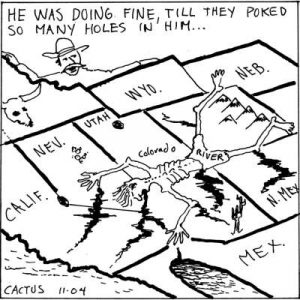

The burros come from rangelands in Colorado, Nevada, California, Montana, Nevada, Wyoming, Oregon, Idaho, and Utah. The Bureau of Land Management is responsible for managing public lands, and that responsibility includes minimizing the negative impacts of both domestic and wild animals on the rangelands. Because the burro has no natural predators and reproduces at a rate of 18% a year, the BLM must determine what impact they have on the environment.

The Wild Free-roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 states that private citizens cannot harass or remove wild horses or burros. Official removal from the rangelands is determined by a number of considerations and can only be done by an authorized agent. An analysis of the burros’ impact on the environment, whether the animals have overpopulated the range, and the health of the herd are considered.

If any of these factors indicate that burros should be moved, the animals are gathered from the range using a helicopter, which can take a few days to a couple of weeks depending on the number of animals. The BLM has found that helicopters are the most humane and least stressful way of relocating herds.

The horses or burros are then loaded onto a truck for transportation to a holding area and separated according to age and sex. Every effort is made to reunite mares and Jennies with their foals. Then it is decided which animals will be sent to a prepared facility for adoption and which will be sent back to the range. Usually older animals are not readily adopted by the general public, and are therefore returned to the wild.

After working in the Wild Horse and Burro Adoption program for a time, Amy, who now lives 15 minutes from Cañon City with her husband Jerry, decided to adopt a wild burro and train it herself to see just how hard it would be.

“I choose Poncho because I thought he was cute and he was nine years old. The older they are, the harder they are to train. I wanted a challenge,” said Morrison.

BUT SHE FOUND Poncho very easy to train — much more so than a wild horse. “He did really well. Instead of fighting him, I worked with him and took my time. You can’t give them a lot of pressure. The more pressure you give them the more stubborn they become. It takes time and patience. You need to be nice and light with them. They can be gentled in a week or two and the younger they are the easier they are to train,” said Amy.

While training Poncho, Amy found that burros are very intelligent and curious, but they tend to be creatures of habit. “They get used to where they go and what they do. I find in certain situations Poncho doesn’t want to go, so I let him decide that it is okay. If he needs it, I get behind him, but not too close. You need to be careful,” she said.

Burros have a reputation for kicking and Poncho is no exception. Amy explained, “They don’t kick at you, they try to kick you. I never allowed that [with Poncho]. I never allowed him to turn his hind quarters to me.”

While training Poncho, Amy used a small round pen to start brushing and petting him. She spent time with him each day, which developed a strong bond between them. “In round pens they don’t have a corner to hide in and it makes it easier to work with them. Some burros are more difficult, but once you start petting them they know you won’t hurt them.”

As Amy put Poncho through his paces you could see his trusting response to her. Her patience and time has resulted in a sweet, gentle burro that can be ridden and led with little resistance.

Amy thinks burros make good pets. “They can do a good job of keeping the weeds down and also keep predators away. There are ranchers who put the burros they adopt in with their cattle and they’ve found that it is a very good way to protect their livestock.”

Poncho is now 11 years old and seems to be quite content to roam the Morrison’s ranch. With three sides of their ranch flanked by BLM land, Poncho has plenty of room to roam. Amy has noticed that Poncho prefers the land that has cactus and barren, rocky ground over the more abundant grassland.

“Poncho is from the Cibola-Triso region near Blythe, California, and I think he feels very at home here. Burros are really tough little animals and have a long life. They can live to be up to 30 years old,” she said.

PONCHO HAS FOUND his place in Amy Morrison’s heart as well as on the Morrisons’ ranch. He spends his days grazing on weeds and finding shade in the hills. He plays with the dogs, chasing them one minute, then being chased by them the next. Whenever a car comes down the road, Poncho is right there to see who has come for a visit. He always knows when to come home for the night to get his hay and be put in the corral with his best horse friend, Tek.

Amy Morrison smiles and her eyes shine when she talks about Poncho. “He is a good buddy,” she says.

If burros could talk, Poncho would probably say the same thing about Amy.

Sunnie Sacks is a free-lance photojournalist who happily lives in Guffey. She can be contacted at sunnie@sunniesacks.com